Ways of Looking

What is a lyric essay? It’s a hybrid form that sits somewhere between an essay and a lyric poem. According to John D’Agata and Deborah Tall in the Seneca Review, “The lyric essay partakes of the poem in its density and shapeliness, its distillation of ideas and musicality of language. It partakes of the essay in its weight, in its overt desire to engage with facts, melding its allegiance to the actual with its passion for imaginative form.” Read more about the form via the links below. Our first lyric essay is by Kim Moore.

Ways of Looking

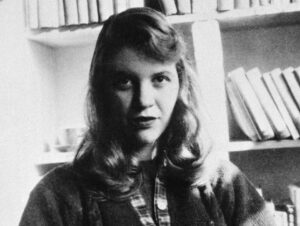

In the photo, I am standing with eyes glazed, drinking from a bottle of beer.

/

In the photo, I am standing with my best friend, who has a bottle of beer in one hand and a whisky and coke in the other. We are in a nightclub. We are in our twenties. We are not afraid of anything.

/

In the photo, a man stands in the middle of two women. He has his arm around the neck of one, whilst holding a bottle of beer, and his arm around the shoulders of the other. He pulls them both towards himself, closer, closer.

/

In the photo, I am in a nightclub in the time before violence, before I knew its real name, before I followed violence to the flat with the red door.

/

In the photo, I am in the time of who-I-thought-I-was, in the time of dance-all-night, in the time of £1-a-bottle, from sweets-sold-in-nightclubs, in the time of glazed-eyes, in the time of my-body-in-the-grasp-of-another, in the time of who-was-that-fucking-man-anyway.

/

This photo, this photo – I can still smell the whisky and the sweetness of sugar, after all these years, after all this time.

/

In Roland Barthes Camera Lucida, he argues that photographs, or at least the photographs that interest him have something he calls a ‘punctum’ which he describes as a wound, a ‘sting, speck, cut, little hole’.

His mother has recently died, and he returns again and again to a photo of her at five years old, although we never get to see that photograph. He says ‘For you, it would be nothing but an indifferent picture … but in it, for you, no wound’.

/

I share Barthes’ astonishment at the photograph, at its irrepressible ability to testify to what was there, to what existed. Once I existed – the photograph is ‘reality in a past state: at once the past and the real’.

/

How that photo takes me back to the Fab Café where the bouncers knew our names and looked after us, bringing us from the back to the front of the queue so we felt chosen and looked after and special and brought us in from the winter streets to the heat of the club brought us in without touching us without expecting anything those men those men with the shoulders and the leather jackets they wanted nothing except our gratitude standing with their arms crossed and the smile that just touches their faces where are they where are they now?

/

Glick et al. (2004) identified two types of sexism – benevolent sexism and hostile sexism. Hostile sexism is perhaps self-explanatory, but defined by Glick et al as covering any type of hostility ‘towards women who challenge male power’. Benevolent sexism is more complex and encompasses ‘attitudes that are subjectively benevolent but patronising, casting women as wonderful but fragile creatures who ought to be protected and provided for by men’. In various studies, a correlation has been found between high levels of benevolent and hostile sexism, proving that these two types of sexism are interconnected and support each other.

/

How the flat with the red door swallowed me whole, how I walked in with violence, not quite arm in arm, not quite following, not quite leading, but I did walk in, not quite with my eyes shut, not quite with my eyes open, it was a strange time, it was a before-time, it was many years ago and I do not remember, except the red door and the way it closed, the way it would not open, or if it did, it opened onto a world that violence also lived in, a world that violence also owned.

/

Outside the flat with the red door, a man at the bus stop follows me to the shop to offer me money to have sex. He follows me back home again. He knows where I live, waits outside at the bus stop and stares at the window. I keep the curtains shut tight, but every time I move them, he’s still there and he smiles when he sees the curtain pulled back.

/

Oh but none of these things have happened yet to the girl in the photograph!

/

Ten years after the photograph was taken, I am working in a men’s prison, and one prisoner gives me his prisoner number and asks me to write to him, to help him with his poetry, with his song lyrics, and then another prisoner, before I can speak, tells him to get walking. The first prisoner turns, walks quickly away. The second prisoner apologises and takes the number on the scrap of paper from my hand, before I can say anything. He tells me he will sort this out, that I will not be bothered again.

/

When I was seventeen, two years before the photograph was taken, I am allowed to go to a particular nightclub because my father’s friend is the bouncer and he will keep an eye on me, keep me safe. My father takes me there and picks me up again.

/

I have walked under the protection of men. I have walked without the protection of men.

/

My father’s friend and the way that he looks at me, and how I use this, to get my friends in the door, especially my friend with the face of a child, who gets turned away everywhere else, especially her, who is kept out of every pub and club, even with her fake ID. My father’s friend lets her in with a nod of his head and tells me not to let her go to the bar. I smile and hug him, standing on tiptoe to reach.

/

According to the national charity Refuge, 1 in 3 women in the UK will experience domestic violence during their lifetimes, and it often starts with benevolent sexism – a jealous partner will be seen as being protective rather than possessive, or caring rather than controlling, nurturing rather than stifling.

/

Behind the red door is a communal hallway and then stairs leading up but past the stairs is my front door, is our front door, and behind that door is the living room where and the kitchen where and the bedroom where and the garden where

/

In Living a Feminist Life Sara Ahmed wrote that ‘we all have different biographies of violence’. I am interested in what a biography of violence would look like. How one biography of violence can hide another. I think about Kenneth Koch’s poem, his one train may hide another, his ‘One dog may conceal another / On a lawn, so if you escape the first, you’re not necessarily safe’. Behind the experience of domestic violence, behind the red door, behind this biography, lies another biography of violence which led me up the steps, which allowed me to open the door.

When Sara Ahmed writes ‘what do we do when these kinds of things happen? Who do we become?’ I have never known the answer. I would also ask who do we become by choosing to look, or not to look? Who do we become when we speak, or stay silent, or write about the moments we stayed silent?

/

In the photograph, a man’s arm is slung around my shoulders as if he knows me, I am so close I can smell him, and I am bringing a bottle to my mouth as if I like it, as if I’m asking for it

/

Barthes argues that the punctum gives a photograph what he calls a ‘blind field’. He argues that a blind field means that any figures in a photograph ‘continue living’ – they have a whole life external to their captured image. If the punctum in my photograph is that man’s arm around my neck, then all of the continuous living the ‘I’ that is captured in that photograph does, will be done forever with an arm around my / her neck, will be done forever with my face so gently trying to escape just by turning away, an escape without drawing attention to myself / herself.

/

In the poem ‘Monument’ by Elizabeth Bishop, the reader is asked to look again and again at the monument, described in painstaking detail. Bishop asks us:

Now can you see the monument? It is of wood

built somewhat like a box. No. Built

like several boxes in descending sizes

one above the other …

(Bishop, 1983:23)

The first time I read Bishop’s poem, I felt as if I was walking round and round the monument, seeing it from every angle, without really seeing it at all.

If this essay could transform into a single poem, it would be this one. Imagine this essay as a monument. Imagine violence as a monument or sexism as a monument. Now climb inside, crawl underneath, sit on top and look at the landscape which surrounds them both, the paths that lead to them, the sightlines, follow the lines of sight.

Imagine this essay as a poem.

Texts referred to in this essay include:

Ahmed, S. (2017) Living a feminist life. Durham: Duke University Press

Barthes, R (1980) Camera Lucida. London: Penguin Random House

Bishop, E. (1983) Complete poems. London: Chatto & Windus

Glick, P., Lameiras, M., Fiske, S. T., Eckes, T., Masser, B., Volpato, C., Manganelli, A. M., Pek, J. C. X., et al. (2004)

‘Bad but bold: ambivalent attitudes toward men predict gender inequality in 16 nations.’ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

Read Deborah Tall and John D’Agata on the Lyric Essay in Seneca Review

Read Manipulations of the World: On the Lyric Essay by Roxane Gay in Lit Pub