Rowan Bell on the art of Tracey Emin and the poetry of Billy Childish

It’s not often that a tiff between lovers, immortalised in a poem, gives rise to a new international art movement. Legend has it that in 1991 the artist Tracey Emin told her then boyfriend Billy Childish that his art was ‘stuck’ and that this led him to write a poem and later to the formation of ‘Stuckism’.

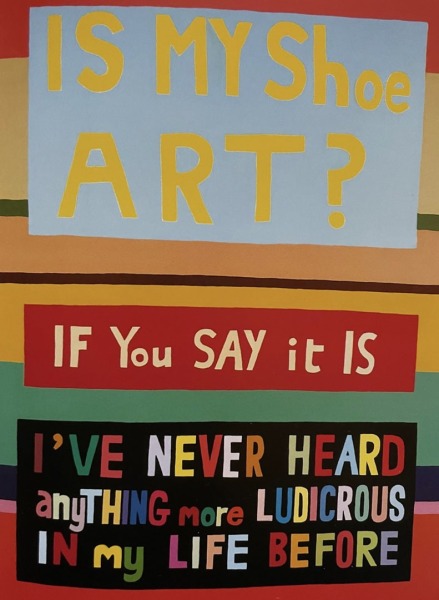

The group’s origins and activities are described on Stuckism.com in an essay by Charles Thompson who, together with Billy Childish, formally founded the association in 1999. The movement is described as “pro-contemporary figurative painting with ideas”; Stuckists say that they are “anti-conceptual art, mainly because of its lack of concepts”. According to the book The Stuckists Punk Victorian that accompanied the 2005 National Museum Exhibition of Stuckist art in Liverpool, there were 80 Stuckist groups around the world at that time; Stuckism has now grown to an international movement of over 160 groups in 40 countries.

The movement’s roots date back to 1979 and the Medway Poets, an English punk-based poetry performance group. After a 1975 reading on the banks of the River Medway (organised by Medway College lecturer Alan Denham, and embodying the chaotic and anarchic energy of punk music culture) the Medway poets met and read their poems in pubs around Chatham and Gravesend. They caught the zeitgeist of the time and, in keeping with punk culture, expressed anger at just about everything, including each other.

It’s not often that a tiff between lovers, immortalised in a poem, gives rise to a new international art movement

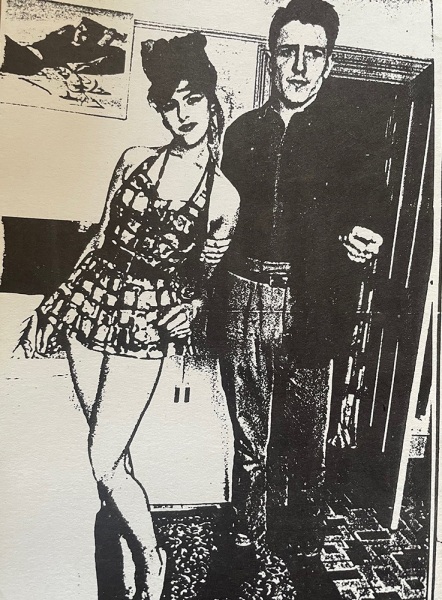

With readings at the Kent Literature Festival and the 1981 Cambridge Poetry Festival, and due to a local television documentary, the Medway poets attracted numerous followers, including the young Tracey Emin. She became close to Billy Childish in what has been described as an “obsessive relationship”. Childish’s name was one of those embroidered in Emin’s conceptual tent art ‘Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995’ that was later lost in the 2004 Momart London warehouse fire and never recreated. Emin was nobody’s muse though; she had clear ideas about her own artistic development, and while the Medway Poets’ anti-establishment anger, exploitation and injustice later became themes in her own work, she charted her own path.

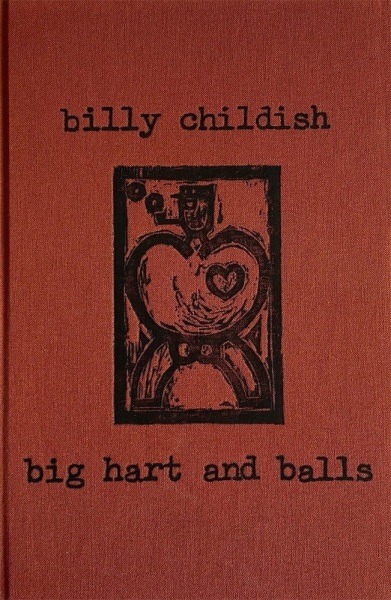

Here’s an extract from ‘poems for a pissed off wife I’, published in Billy Childish’s 1994 collection big hart and balls.

i have to treat him with

kid gloves

he isn’t big enough to take

the message

his paintings are stuck stuck stuck!

he is stuck!

still playing that stupid music

and riting those idiotic poems

Childish says, “Tracey was basically having a hissy fit because I wouldn’t bow down to her demand that I endorse her new kind of art, which I told her was old hat, so she attacked mine.”

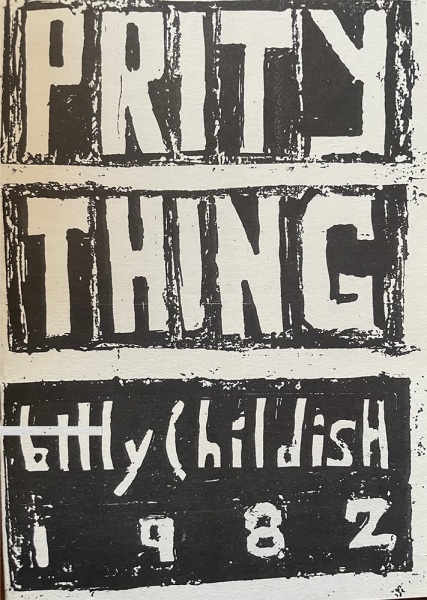

Billy Childish’s Medway poems are simple graphic descriptions of a time of youth when interpersonal relationships merged and budded like amoebae and the external political and economic matrix was Thatcherism. His 1982 pamphlet Prity Thing documents his relationship with the stunningly beautiful Emin:

dollys walking round the room in

nothing but her skirt

with her tits hanging everywhere

paintings of shelia n dolly hang

of the wall

His press, Hangman Books, published Tracey Emin’s first book Six Turkish Tales in 1987. It’s a series of short stories about her visits to Turkey with her father, and contains some striking and well-drawn illustrations by the author. Opposite the hangman frontispiece is a quotation from Edvard Munch: “I shouldn’t like to be without suffering. How much of my art I owe to suffering”. There’s also a poetic homily signed T.E. which reads:

No man, no matter how good, how saintly

can live a life bearing the burden of

his own corpes.

It is there. The truth to disregard,

to believe or disbelieve.

(I quote it with the original spelling; there is a lot of meaningful dyslexia in the Medway poet poems). Both the homily and the full Edvard Munch quotation describe the serious intent of Emin’s artistic intentions and provide a leitmotif for her later work. The longer quotation from Munch reads: “No longer shall I paint interiors, and people reading, and women knitting. I shall paint living people who breathe and feel and suffer and love – I shall paint a number of pictures of this kind. People will understand the sacredness of it, and will take off their hats as though they were in church.”

The rest as they say, is history. Charles Saatchi, an advertising executive who made his fortune in the Thatcher years, bought and promoted conceptual art by the Young British Artists, a group which included Tracey Emin. Her work ‘My Bed’, created in 1998, was shortlisted for the Turner Prize with much media controversy. The Stuckists, dressed as clowns on the premise that the Tate had been turned into a circus, protested against the rise of conceptual art in the established art world, leading to a rift between Emin, the Stuckists, and the former Medway poets. In an interview for the Sydney Morning Herald in 2003 she said: “I don’t like it at all … I don’t really want to talk about it. If your wife was stalked and hounded through the media by someone she’d had a relationship with when she was 18, would you like it? That’s what happened to me. I don’t find it funny, I find it a bit sick, and I find it very cruel, and I just wish people would get on with their own lives and let me get on with mine.”

In 2021 Emin put together an extraordinary exhibition of her paintings in the Royal Academy together with a selection of Munch pictures entitled ‘The Loneliness of the Soul’. Whatever your opinions of Emin vs Munch, the exhibition opened an interpretation of both artists that had not been seen or acknowledged by previous art commentators. It takes one to know one.

Tracey Emin has openly discussed the sexual abuse and exploitation she experienced as a child and young woman, and the apparent normality of it, described in the spoken prose poem from her short film ‘Why I Never Became a Dancer’, reproduced in her autobiographical book Strangeland.

It didn’t matter that I was young

thirteen, fourteen.

It didn’t matter that they were men of

nineteen, twenty, twenty-five, twenty-six.

It never crossed my mind to ask them

what the attraction was.

I knew

sex was what it was.

Emin’s art graphically reflects her lived experience and speaks with direct honesty to many people who have no voice and who have had to accept becoming trapped in unequal sexual power dynamics that dominate and derail their lives and aspirations. She was able to express power inequalities in the art world in a uniquely personal way. Her appearance as a panellist on the 1997 live show Is Painting Dead is worth watching both for her own inarticulate frustration and for the ‘arty bollocks’ of the other panellists. Emin is the only person on the panel making sensible comments even if she can’t string a sentence together and walks out before the programme finished.

There was also an international inability to understand what Emin was saying. In 2003 The Sydney Morning Herald ran an article about her first Australian exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, saying: “And you know things are going bad when Australian entertainer Rolf Harris joins the fray, publicly describing her work as ‘a con’.” Now there’s a comment that didn’t age well. In the unfolding light of subsequent knowledge, time has revealed the truth in her art, and the con in Harris’s words.

Tracey Emin is perhaps at her poetic best when she speaks. As with her art, it is the guileless honesty that cuts through

Tracey Emin is perhaps at her poetic best when she speaks. As with her art, it is the guileless honesty that cuts through. Here is a short extract from her 2004 interview on the BBC programme Desert Island Discs describing the time when she jumped into the sea from the harbour wall in Margate. I went back to listen to it again to transcribe the segment. Chop it up into lines and it’s a pretty good poem: “My feet went into the sand and then I came back up like a cork and I remember looking up and feeling stupid and really insignificant and really tiny and there’s all the stars so what could have been a tragedy actually ended up being really beautiful and I think that it was one of the first true times in my life that I understood about nature completely.”

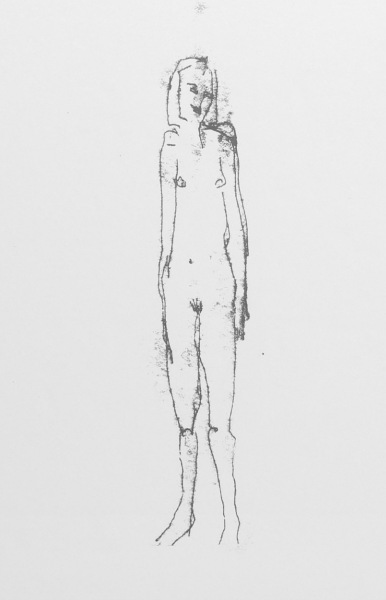

It’s also important to look at the varied oeuvre of Tracey Emin’s art to see beyond the splayed bodies. Here’s Emin from an interview with the Guardian in 2009: “It took me years to understand the magic of drawing. For years, I tried to make things look how they are – instead of being what they are.” Her description of the exquisitely drawn 1995 picture ‘If I Could Just Go Back and Start Again’ is also almost a poem in itself: “I spent seven years learning to draw, and this makes me realise how worthwhile the lessons were. The drawing has the innocence of a young girl staring out beyond the picture. It makes me want to jump into the paper, grab hold of the girl – who is me – and shake her and tell her everything is going to be all right. I wonder if drawings can be the imprints of our souls? Maybe some drawings existed before they were actually made, and they just float around in the ether like ghosts, waiting to appear on paper.”