Chris Edgoose reviews The Dereliction by Liz Berry and Tom Hicks (Hercules Editions, 2021)

“What are you looking for?” Liz Berry asks photographer Tom Hicks in the interview at the end of The Dereliction. Hicks replies that his aim is to explore “the atmospherics of a place”, and he goes on: “My images don’t feature people but are almost always about people and the traces of their activity.”

It’s these traces of people’s lives in abandoned, ignored and derelict places that Berry picks up and weaves, with her uniquely tender and musical, dialect-driven, voice, into a sequence of poems (perhaps ‘movement’ would be a better word) which is as ethereal as it is organic and as erotic as it is haunting.

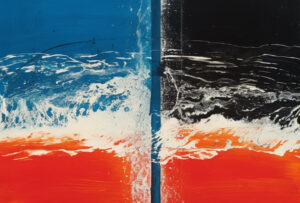

The poems and photos of The Dereliction could of course exist in isolation from one another, but both would be diminished by the separation, I think. For this reader, each pairing bleeds into single impressions that seem to hang above the small, square, double pages of this lovely pamphlet like little ghosts.

Here you will find names scratched in brick and wood, empty buildings, lonely canals, the corrugated iron of factories, and the black rusted iron of horse sculptures in railway sidings. Each is photographed with great sensitivity and extrapolated in short verses invoking fertility goddesses, transformations, butterflies, birds, earthy life and motherhood. Each pairing is a dream-like memorial to unnoticed post-industrial lives, to love, to sex and to childhood’s end.

And as you look between the photos and the poems over the pamphlet’s forty-seven pages, a whole world of ghosts emerges. It is an insubstantial world, naturally, an indefinable world, perhaps like Berry and Hicks’ Black Country itself (“There’s no map. Forget that.” Berry writes at the outset, in the wonderful, tone-setting sonnet ‘Secret Garden’), but it’s a world heavy with physical experiences and sensations, and the memory of both.

Here you will find names scratched in brick and wood, empty buildings, lonely canals, the corrugated iron of factories, and the black rusted iron of horse sculptures in railway sidings

On the inside cover there is a map which broadly covers the area referred to as the Black Country, but this is at least partly ironic: the world of the pamphlet cannot be defined by geographical borders alone because it speaks to the past and the future as well as the present. The borders it discusses are ‘the traces’ themselves, they are the borders which lie between what is there and what is no longer there, what is present and what is absent, living and dead.

The final poem of the sequence (‘Iron Oss’) turns the decorative iron horses that were placed along the railway line between Wolverhampton and Birmingham in the 80s into sentinels tasked with guarding the inhabitants of this over-looked world of pit-banks, pubs and housing estates:

Watch over us all, little osses,

[…]

Watch over those who have long gone,

taken the dawn train on a one-way ticket

and those not born yet, sweet unseen passengers

still held in the darkness, waiting for the signal…

(from ‘Iron Oss’)

“Us all” here is not just the people of Tipton, Dudley and Bilston; it really is us all. More than ever in this pamphlet, Berry universalises the local.

And as always, she walks a fine line between cultural memory and nostalgia, between tenderness and sentimentality; but in all Berry’s writing I have yet to feel that she crosses onto the wrong side of that line. The tension there is part of her work’s power, along with her juxtaposition of an almost High-Poetic diction (e.g. her use of ‘upon’: “I want you to walk upon me, love” in ‘Monmore Green’; “keep watch / upon the darkness” in ‘Godspeed’) with the very different – though no less poetic – rhythms and associations conjured by the use of Black Country dialect words for which she has become well-known (the jimmucking pigeons, the iron osses, the wenches and babbies, the “lonely wammel”, “the cut’s copper looking glass”).

The Dereliction

Love me like that pub on Darkhouse Lane, sweetheart of wet-the-beds and creeping rot.

Love me like I have no windows, no doors, just wild blue streaming through unarrested.

Love me to the bare bones, through rain and rough weather, time singing its song of dereliction dereliction.

Touch your palms to my walls, their yielding brick, and remember how my face held its look

of abandon, how young we were, my white dress lifted and blown reckless as a kite in a storm.

In fact, as in her last pamphlet Republic of Motherhood (Chatto & Windus, 2018), many of the poems in The Dereliction, certainly those towards the beginning, play down dialect to the extent that it is more seamlessly embedded in them than in her first collection Black Country (Chatto & Windus, 2014), and here for the first time she does not draw attention to them by offering translations. These are the words I use, she seems to be saying, if you don’t know them, work them out or look them up.

Does this signify an ongoing maturing of her poetic voice? Well, it certainly feels like a development and an evolution, which goes hand in hand with an extension of her themes.

There are direct lexical links back to both her previous works; the jimmucking flight of the pigeons in ‘Princes’ End’, for example, takes us back to ‘Birmingham Roller’ in Black Country; but while in the earlier poem it was one dialect word among a thrilling whirlwind of vernacular, here it is one of only two. In the earlier poem, the poet gazed at a bird “jimmucking in the breeze, somersaulting through / the white-breathed prayer of January”; here she holds the pigeon gently in her hands “to steady the jimmucking flight in her” and she thinks of her new-born child:

… when I fanned her feathers to the light

[…]

I saw the ghost of the new wing shining beneath,

how I too might become the bird you needed.

(from ‘Princes End’)

The focus has moved from the sky to the earth (“There’s nothing of ascension that I want now” she says in ‘Monmore Green’). Where there was movement and verbal brilliance, here there is stillness and contemplative quiet. The effect is no less brilliant.

The quote from ‘Princes End’ above also illustrates one of the thematic evolutions in The Dereliction: that of bodily transformation and a fascination with the metaphorical potential of birds. Black Country opened with ‘Bird’: “When I became a bird, Lord, nothing could / not stop me.” Now the metamorphosis is both maternal and shared:

She was you and she was me,

the black winter of birth behind us

like a storm blown to the sea

(from ‘Princes End’)

These lines strike me as beautiful, perhaps more so than any Berry has ever written, but they carry a weight of experiences that her 2014 collection could never have expressed. And there is loss here now too, which the ornithological imagery is extended to include. In ‘Chloe’, a lost youthful love combines powerfully with what I take to be a miscarriage in a dreadfully desolate final image:

But the air’s already turning and September waits

like a dream of falling, the egg blown,

the nest in the ash a casket for leaves.

The images here are all of the body and of the earth, carnal and fetid, but also ravaged by time and weather. The ‘I’ of these poems transforms not only into birds, but into the earth itself (“smell me in wild garlic and rotting blossom” (‘Monmore Green’)), and into ruined buildings (“Touch your palms to my walls, their yielding brick” (‘The Dereliction’). The decay and ageing is not just juxtaposed with the eroticism of these poems but tied into it intrinsically.

Bones, too, return time and again. “Love me to the bare bones” pleads the ‘I’ in the title poem, and in ‘Glasshouse Bridge’ recollects: “I loved a boy once, to his silver bones”. It is as though love and memory, like wind and rain, have stripped everything away from the individuals whom the poems recall or address, exposing them down to their skeletons – the last traces of their existence.

The Dereliction welcomes this exposure and gives itself to the inevitability of time’s destructive embrace, celebrating vestiges of those no longer here, passions of those still present, and hopes for those to come.

Chris Edgoose is a poet and blogger at Wood Bee Poet. He lives near Cambridge in the UK, and has had work published in several magazines in print and online.