Pedro Baños Gallego on the ‘forbidden’ poems, and the irresistible rise, of Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal

In the 19th century, French poetry underwent a period of renewal. It was a time of divergence and contrasts; many authors and artistic schools began to apply a very personal way of seeing the world to their literature. The result was the great variety of literary currents at the time: Romanticism, Realism, Naturalism, Symbolism and Decadence, among others.

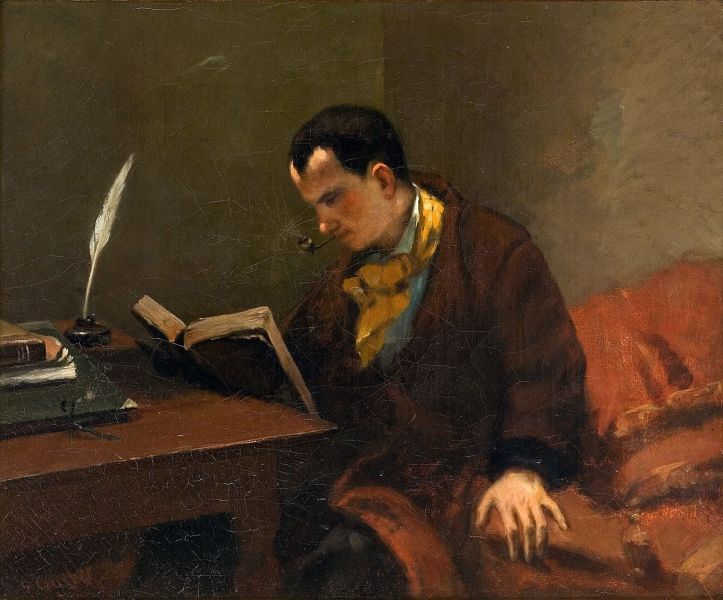

It was in this context of artistic diversity that authors such as Charles Baudelaire emerged. Later classified as one of the ‘poètes maudit’ (‘damned’ or ‘cursed’ poets), Baudelaire lived through the 19th century in the manner of the bohemian youth around him. From alcoholism to opium consumption by way of prostitution and venereal disease, Baudelaire’s life was far removed from the Catholic morality that was then dominant in society. Given the exploration of the personal that characterised 19th century literature, it is not surprising that these themes came to permeate Baudelaire’s artistic output.

Les Fleurs du Mal

Baudelaire’s most famous work is undoubtedly Les Fleurs du Mal. This collection of poems, which had such an influence on poetry, was rewritten and modified several times before it was finally published.

Two editions appeared during the author’s lifetime, with substantial changes in their structure: the 1861 edition did not include the six censored poems, but added 32 others, while a partial publication by Auguste Poulet-Malassis in 1866 dared to include the ‘forbidden’ poems. The first edition considered definitive was the posthumous edition of 1868. But the 151 poems in this version don’t include the censored texts either.

Why were these poems ‘eliminated’ from the work?

From the first publication of Les Fleurs du Mal, on 25 June 1857, Baudelaire’s immoral life (and therefore his literature) aroused great controversy: six poems were censored on the grounds of blasphemy.

A few days later, in its 5th July edition, the famous newspaper Le Figaro published the following review of Les Fleurs du Mal: “This book is a sanatorium open to all the follies of the soul, to all the putrefactions of the heart; though it would cure them, they are incurable.”

After several press articles were published describing the work as immoral, the case was brought before the courts: on 21 August of that year, Baudelaire was convicted of an offence against morality. In addition to a fine of three hundred francs, the court decided to ban the poems ‘Les Bijoux’, ‘Le Léthé’, ‘À celle qui est trop gaie’, ‘Lesbos’, ‘Les Femmes maudites’ and ‘Les Métamorphoses du vampire’.

It was not until 1949 that a French court lifted the ban on the publication of these texts, ruling almost a century later that “the poems in question do not contain obscene or even coarse language and do not exceed, in their expressive form, the freedoms allowed to the artist”.

Putting an end to the idealized woman

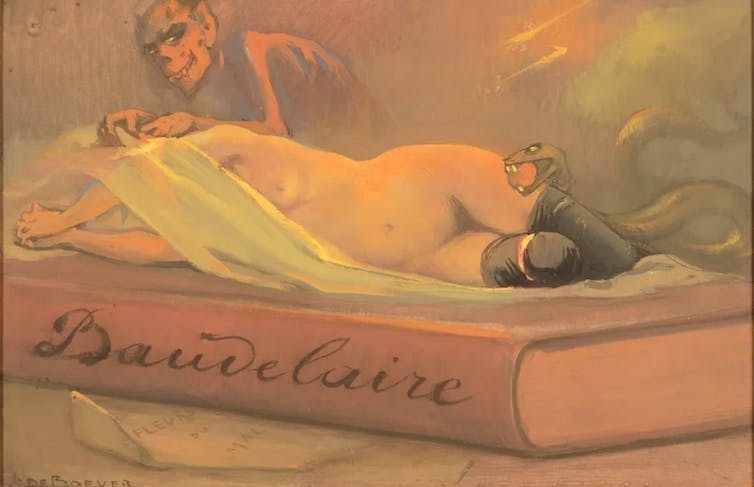

One of the main arguments behind these denunciations rested on the image of women in Les Fleurs du Mal. Baudelaire explored the female subject from an angle that ran profoundly contrary to the moral standards of nineteenth-century France: lesbianism, sadism, prostitution and explicit eroticism had no place in the eyes of the Catholic censors of the time.

It should be remembered that France, despite the French Revolution, did not become a non-denominational state until 1905. The crimes of ‘offence to public morality’ or ‘offence to religious morality’ were still fully in force in the 19th century, which shows how much influence the Church still had in France at that time. To take another example, Gustave Flaubert’s famous work Madame Bovary was heavily attacked five months before Les Fleurs du Mal, for the same reasons.

Baudelaire took the ideal, glorified woman of the Romantic movement and juxtaposed her with what he knew was on the other side of the coin: prostitution and the femme fatale were concepts as real to the author as the woman who was an object of worship. While Baudelaire’s female sources of inspiration (Marie Daubrun, Madame Sabatier, Jeanne Duval and his own mother) were figures revered for their sanctity and goodness, Baudelaire analysed in depth the darker aspects of his relationship with some of them.

In ‘Lesbos’, for example, the author explores, through various images, a sadism inherent to the female condition:

Tu tires ton pardon de l’éternel martyre,

Infligé sans relâche aux cœurs ambitieux,

Qu’attire loin de nous le radieux sourire

Entrevu vaguement au bord des autres cieux!

Tu tires ton pardon de l’éternel martyre!

From martyrdom your pardon you beguile,

Inflicted without stint on hearts that soar

Far, far away, drawn by some radiant smile

Seen vaguely on a strange celestial shore.

From martyrdom your pardon you beguile.

— Roy Campbell, Poems of Baudelaire

(New York: Pantheon Books, 1952)

Similarly, in ‘Les Métamorphoses du vampire’, Baudelaire adds to this clearly harmful desire images which, at the time, were shockingly erotic:

La femme cependant, de sa bouche de fraise,

En se tordant ainsi qu’un serpent sur la braise,

Et pétrissant ses seins sur le fer de son busc,

Laissait couler ces mots tout imprégnés de musc :

“Moi, j’ai la lèvre humide, et je sais la science

De perdre au fond d’un lit l’antique conscience.

Je sèche tous les pleurs sur mes seins triomphants,

Et fais rire les vieux du rire des enfants.

The woman meanwhile, twisting like a snake

On hot coals and kneading her breasts against the steel

Of her corset, from her mouth red as strawberries

Let flow these words impregnated with musk:

— “I, I have moist lips, and I know the art

Of losing old Conscience in the depths of a bed.

I dry all tears on my triumphant breasts

And make old men laugh with the laughter of children.

— William Aggeler,The Flowers of Evil

(Fresno, CA: Academy Library Guild, 1954)

Finally, in the poem ‘Femmes damnées (Delphine et Hippolyte)’, Baudelaire clearly presents a lesbian relationship between the two women. Throughout the poem, eroticism and reflections on lesbianism succeed each other in equal measure:

Ne me regarde pas ainsi, toi, ma pensée !

Toi que j’aime à jamais, ma sœur d’élection,

Quand même tu serais une embûche dressée

Et le commencement de ma perdition !

Do not look at me that way, you, my dearest thought:

The sister of my choice whom I’d love forever

Even if you were an ambush prepared for me

And the beginning of my perdition.”

— William Aggeler, The Flowers of Evil

(Fresno, CA: Academy Library Guild, 1954)

A born provocateur

Although modern readers may feel that these themes have already been widely addressed across all art forms, to the public of his time Baudelaire was a true provocateur. Woman, previously idealised, now represents an angel-devil duality that included the most sordid aspects of the author’s experience. Moreover, Baudelaire makes explicit certain ideological and moral conflicts whose foundations are none other than the clash between the unrealistic image of the ‘good woman’, Catholic and pure, and the raw reality that surrounded him. In her, goodness and delinquency, explicit sexuality and modesty, prostitution and moralizing censorship coexist. These were reasons enough to consider censoring the poet at the time, but not enough to stop the irresistible rise of Les Fleurs du Mal.

This article is translated and republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Read the original article in French.