Karen Smith reviews Moon Jellyfish Can Barely Swim by Ness Owen (Parthian, 2023)

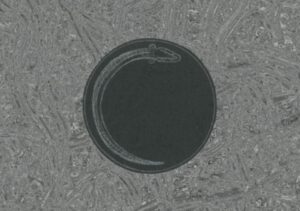

Even with my lilting limbs, bumpy breaststroke and skew-whiff screwkick, if I found myself among a fluther of moon jellyfish I wouldn’t panic. After reading Moon Jellyfish Can Barely Swim, I know I’d pretty easily out-swim their aimless, brainless barbs. But though they’re dismal navigators, I’d be a fool to underestimate “one of the most successful organisms of animal life”, according to Ness Owen. Her awe for their hardiness is evident in the list of facts at the front of the book which points to their future flourishing despite – or possibly due to – the destructive impact of industrial processes on the oceans.

The energy that glows sublimely through Owen’s work has transformative potential. Her first stroke is reminiscent of Wallace Stevens. In ‘Put the girl on the shore’, she says: “Let her alone with / the currents […] Let her fall, deep / from dislocation // into the subtle art / of breathing out”. In ‘You can’t save everyone’, she explores the fluid darkness of the human mind: “your fear grows / bigger with every tide”. And she ends ‘Birth of a Medusa’ with a Woolf-like resurfacing “safety is / a bloom of your own.” In ‘My thirst to know won’t end but why should we be the same?’ she uses the intertidal zone to explore the weathering of communicative intimacy between adult child and their parent. “Your feet half the size of mine / but I always felt bigger even when I was small.” She carefully exposes the vulnerable silt of memory: “you / remember the child taken by the wave”.

Early in the collection the work is rhythmical and strong, with sensitive, sensual portraits of the power of seawater. This strength fades a little as Owen’s fondness for poem-head quotation begins to look circular. For example in ‘Birth of a Medusa’ she tops the poem with a rather over-explanatory: “Jellyfish have a polyp phase when they are attached to coastal reefs, and a medusa phase, when they float among the plankton”. The body becomes a little unanchored too, in ‘Conditions’:

Isn’t life full of fades

and surges and this

waiting for the right

conditions?

But this is soon tempered by the poet’s humour and passionate call for environmental justice. In ‘Not another sea poem’, Owen deploys repetition to define her poem by what it won’t do, shoring up surges of energy like a hydroelectric dam, only to thunder forth in the final line: “stop / dumping your shit in the sea” (italics hers). The water itself is political, a language of liquid solidarity that just won’t pipe down. In ‘Sometimes’ she says:

Silence is the weight of

water when we fight for

air, and graffiti is our voice

to shout.

‘Jab’ is one of a fistful of poems that bears the mark of Covid. It’s a compelling narrative piece that exemplifies the storytelling so vital to Owen’s verse. The ways in which time can change a person almost beyond recognition become poignantly clear. Losing track of our very being – as the woman leading her own search party does in ‘Spoor’ – comes to stand for the tragi-comedy of the anthropocene, as well as the disorientation many feel when unheard: “without / her words, she too was lost” (‘Her words’).

The energy that glows sublimely through Owen’s work has transformative potential

‘Notes on a Vowel Hungry Language’ pairs lashings of tongue-barbs against the “cat-walking-across-the keyboard” Welsh language alongside a fatter column of affirmation: “words grow into worlds if / only you’d let them”. The poet’s compassionate campaign for diversity – of species, of language, of stories, of minds – throws light on the threat to natural forms, whether human or other. In ‘Nain limps through my dreams’:

town is afraid, town is angry, town loses her tongue,

town gives up.

As you’d expect of verse in the spirit of the moon jellyfish, the poems are realised in free-flowing forms. They are experimental, lithe and responsive to their subjects. But as the collection progresses (particularly in the last section) they become less disciplined in a way that slows energy and pace, whilst still propelling the reader. I began to long for more structure and musicality, particularly at the passive, lightweight line endings. For example, in ‘Ffynnon Gwenfaen’ (Genfaen’s Well):

It was so easy to give up in the

summer scorch of grass, imagining it

wasn’t our time to find this place, to

offer two stones to cure us of what is

woven beneath our skin.

The strongest pieces in this collection unite multiple linguistic effects with elegant and moving simplicity. ‘Magu Adenydd’ harnesses the unique compression of the Welsh language to evoke a deft fable-like wisdom, balancing precise diction, transcendent gravity and the title’s dual meaning – growing wings / leaving home – to perfection:

Sometimes we fall

to earth. Sometimes

someone will catch us.

Owen skilfully elevates the focus in ‘Disturbing the artist’, her ekphrastic homage to Edward Povey’s spectacular mural at the University of Wales. The painting’s central focus – a man with wings embracing a child – speaks to intergenerational drift: “Pour / your life over his shoulder / knowing he won’t look back”.

Encircled by the rugged waters of the Anglesey coast, Owen lands her poems “between lecturing and farming”. In the short interview at the back of the book, she summons the power of the writing process “to remember, or to try to understand”. In her hands, the poem-vessel drops anchor against dissolution and breakdown. Her hymn to the jellyfish launches us into waters of political unrest, merging environmental, familial, national and linguistic currents. I will remember the watery wisdom of their desultory radiance in ‘How we glow’:

We are braver than

we know. Even in

the smallest light

watch how we glow.

Karen Smith is a wild swimming enthusiast, librarian and poet from Uckfield, East Sussex. Since 2018, she’s been collaborating with Kin’d & Kin’d, an Eco-poetry collective of writers and artists. Her pamphlet Schist was published in 2019 as part of the Laureate’s Choice Series and she is currently working on a first collection inspired by water.