Hilary Menos reviews Poetry Projects to Make and Do edited by Deborah Alma (Nine Arches Press, 2023) and On Poetry by Roger Robinson (2023)

The Friday Poem doesn’t normally publish costs, because they vary from site to site, but they might be relevant here if you’re trying to decide which – if any – of these books to buy. This week we’re looking at Deborah Alma’s Poetry Projects to Make and Do (Nine Arches Press, 2023, £16.99) and Roger Robinson’s On Poetry (Gumroad, £10 digital download). Next week we’re reviewing The Process of Poetry edited by Rosanna McGlone (Fly on the Wall Press, 2023, £10.99) and On Poetry by Jackie Wills (Smith|Doorstop, 2022, £10.99 or £1.40 digital download).

Poetry Projects to Make and Do edited by Deborah Alma (Nine Arches Press, 2023)

Deb Alma, who edited this book and provides the lively and entertaining introduction, is also is the founder of the Poetry Pharmacy – a shop selling all things poetic, with a focus on well-being. This theme – well-being – pops up repeatedly throughout Poetry Projects to Make and Do, from Caleb Parkin’s chapter on the ‘Practical Sides of Wellbeing for Poets’ to Clare Shaw’s essay on ‘Working with Vulnerability in Groups’ and Roshni Beeharry’s piece on writing with healthcare staff, students and those with health conditions. So much so that at times it reads rather like a self-help manual, full of references to finding your own truth, the validity of lived experience, the need for ‘safe spaces’ and how to encourage self belief. When did poetry get so … squishy?

The book is divided into three sections – ‘Projects just for you’, ‘Projects for Groups & Collaboration’, and ‘Projects in Public’ – and there is some engaging writing in all three. I was particularly taken by Julia Bird’s chapter on her experiences producing, staging and touring poetry shows with Jaybird Live Literature, the live lit production company she founded in 2006. She describes various theatrical techniques and gives some excellent tips on how to “zhuzh up” even the briefest poetry performance. Helen Dewberry’s refreshingly brisk piece on film poems explores technical aspects of film – the rule of thirds, transitions, and camera angles – and talks about how to use colour and sound to good effect. Meanwhile Jo Bell interviews Dan Simpson, poet in residence at the National Memorial Arboretum, and Tania Hershman, who built herself a residency at Manchester’s Southern Cemetery, and gives some well-thought-out advice on how to create your own opportunities for poetry residencies.

The book is divided into three sections – ‘Projects just for you’, ‘Projects for Groups & Collaboration’, and ‘Projects in Public’ – and there is some engaging writing in all three

Other chapters provide a taster menu of ways in which you might be able to make poetry work for you. There’s advice on how to run poetry workshops, how to write poetry from photographs, and how to bridge the gap between poetry and theatre. Nina Mingya Powles writes about how she made a poetry zine, Arji Maunuelpillai about how he set up a poetry podcast, Tamar Yoseloff how she set up poetry pamphlet publishing house Hercules Editions. Many of these pieces are written along the lines of “what I did …”. They’re easy to read, and more or less useful depending on what sort of thing you’re interested in. Some chapters are rather basic: do we really need to be told, by the organisers of a monthly poetry night, that we should “find a room, for free if you can”? There’s some heavy reading here too – Jane Burn’s fifteen-page essay (plus an entire page of sources) on ‘found poetry’, collage and ‘asemic‘ writing took some getting to grips with, though some of her pictures are lovely, particularly her asemic poem ‘A Garden’s Year Begins’, see our gallery.

More provocative is Jonathan Davidson’s piece on funding, which asks poets applying for funding to “empathise” with funding bodies. He says funders “use their money to make happen the things they want to make happen”, and that Arts Council England (ACE) are “perfectly and delightfully clear about this. They need the things or / and the people they fund to contribute to ACE’s objectives (their Outcomes) and to use ACE’s ‘Investment Principles’ to achieve those Outcomes.” But he doesn’t tell us what ACE’s objectives actually are. At a time when cuts are massive and ongoing, and arts funding seems increasingly to depend as much on on the identity of the poet as the quality of the work, Davidson’s suggestion to “make what you want to do fit in with what they want to fund” doesn’t feel very helpful. A discussion of how the increasingly political nature of ACE has influenced what poetry gets published and rewarded would have been interesting here.

At the end of each chapter, the writer offers some kind of activity. Some of these contain some excellent prompts. Jean Atkin, for example, suggests approaching a local-to-you event, and offering to provide small poems to the public, handwritten or typed, perhaps using the event or festival’s theme. Tie them up with ribbon she suggests, or use sealing wax, but make it playful. Jaqueline Saphra offers a tempting guide to writing poems or even a play about an animal. And I liked the idea, and the tone, of Helen Ivory’s writing exercises. “Most of all,” she says, “have fun with it. Sometimes we forget to play. Play sets us free.”

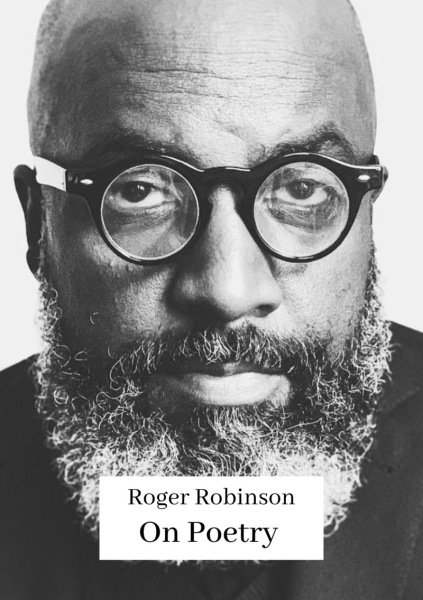

On Poetry by Roger Robinson (2023)

This book is ten quid for a digital download from Gumroad, an e-commerce platform that allows creators to sell digital products directly to their audience. Gumroad take 10%, which means Roger Robinson presumably gets nine quid for every copy sold. This is clearly a much better financial arrangement for him than going through the traditional publishing route. Perhaps not so much for his readers; the final product would have benefitted from some robust editing (there are a number of spelling and grammatical mistakes).

I paid my money (only six quid because it was on special offer) and I got my download. The pages are unnumbered so it’s a bit tricky to find your way around in the book, and the experience is very loud – there are shouty block capitals everywhere – so the end result is a bit like a PowerPoint presentation, or a series of exhortatory fridge magnets. In fact, you could print out pretty much any number of the pages and pin them to your fridge to remind yourself to “WRITE MORE POEMS THAN YOU WILL EVER USE”. There are rather more than a dozen bright red pages interspersed throughout the book, each with a single pithy quote from Robinson (yes, he’s quoting himself) such as “STOP THINKING ABOUT WHO’S GOING TO READ IT. IT’S NOT YOUR JOB TO THINK OF THAT WHILE YOU’RE WRITING IT.” There are twenty or so solid black pages with poetry prompts in large white text, such as “Write a wedding poem for your best friend who you truely (sic) believe is marrying the wrong person. You have to actually read this poem at their wedding because they asked you to write it.” And there’s a series of pages with poetic insights or suggestions, such as “Make sure that your reader can smell, taste, touch, hear and see the moment.” There are also eight pages of pictures. So of the 120-odd pages in the book, only about half contain more than, say, a hundred words of text. I read the whole thing in about twenty minutes. Robinson says the book is for intermediate poets but its format and its brevity makes it feel like a book for beginners. Beginners with a very big fridge, perhaps.

Robinson says the book is for intermediate poets but its format and its brevity makes it feel like a book for beginners. Beginners with a very big fridge, perhaps

On Poetry is advertised as a “book of cheat codes for poets”. Many of Robinson’s “cheat codes” are valid, but I didn’t find them particularly thought-provoking. Here are some examples: “a critique of your poem is not a critique of you as a person”; “talent amounts to nothing without hard repetitive work”; “Always Carry A Notebook/Journal”; and “YOUR POEMS AREN’T FINISHED UNTIL YOU PRESENT THEM TO AN AUDIENCE. IT IS UNFINISHED IF IT IS STUCK IN A DRAWER SOMEWHERE”. On Poetry is great at (loudly) urging us poets to do this and that, but rarely gets down into the nitty gritty of how we might actually improve our writing. It’s all very well instructing us to “land that poem like an olympic gymnast” – but how? I have considerable respect for Robinson as a poet – I’ve read and re-read A Portable Paradise and rate it highly – and I’m sure he’s inspiring to many, but I’m less sure about his qualities as a teacher of the craft. He says poets need to know, for example, how a couplet differs in effect from a tercet and differs again from a quatrain. A discussion of the different effects created by different stanza lengths would indeed be interesting, but there isn’t one. And I just don’t understand some of his advice. “All poets have a secondary focus or component”, he says. “The beats had jazz. Ted Hughes had mythology. Robert Lowell had his family lineage and history. I have the lives and struggles of the Black British community. What is your secondary component and what are you observing that no one else observes when you add it in?” I am not sure what Robinson means by this and I don’t think I have a secondary focus or component (to be honest, I’m not even sure what my first one is). Oh dear.

All in all, to me the book feels somewhat slung together. All respect to Robinson for being entrepreneurial, working outside the traditional poetry publishing system, and presumably managing to make more than the usual buck a book, but there’s limited mileage here for the working poet. If this sort of thing is your sort of thing, however, there’s more. Robinson has published another ebook on Gumroad. On Creativity offers over 100 tips to help you get creative when you’re stuck. “With much of the content battle-tested through years of workshops and conversations with fellow creatives, On Creativity offers an invaluable glimpse, providing insight into the bedrock principles that sustain his enduring creativity.” Also a tenner.

Hilary Menos is editor of The Friday Poem. Buy her most recent pamphlet, Fear of Forks (HappenStance Press, 2022).