Who was Guillaume Apollinaire and why did he make pictures of words? We unpack three of his ‘calligrammes’ – an early contribution to concrete poetry

Guillaume Apollinaire (1880 – 1918) was a French poet and writer of Polish descent. He was one of the foremost poets of the early 20th century, as well as an ardent defender of Cubism and a forefather of Surrealism. In fact it was Apollinaire who coined the term ‘Cubism’ in 1911 to describe the emerging art movement, He also came up with the term ‘Orphism’, an offshoot of Cubism, in 1912, and the term ‘Surrealism’ in 1917 to describe the works of Erik Satie. He wrote poems without punctuation, and tried to be modern in form and subject. He was also a journalist and art critic, and co-founded the arts and literary magazine Les Soirées de Paris. He enlisted to fight with the artillery in World War I in 1914, was wounded in the head in 1916, and died two years later during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918.

Shortly after his death, the French gazette and literary magazine Mercure de France published Calligrammes, a collection of his poems including a number of examples of his concrete poetry. A calligram is a set of words arranged in such a way that the words form a thematically related image. It can be a poem, a phrase, or a single word; the visual arrangement can rely on certain uses of typeface, calligraphy or handwriting, for instance along non-parallel and curved text lines, or in shaped paragraphs. The image (or images) created by the words usually illustrates the text by expressing visually what it says, or something closely associated; it can also, on purpose, show something contradictory with the text or otherwise be intentionally misleading, or can contribute additional thoughts and meanings to the text.

A calligram is a set of words arranged in such a way that it forms a thematically related image

Apollinaire described his work in a letter to French novelist, biographer and critic André Billy. He wrote, “The Calligrammes are an idealisation of free verse poetry and typographical precision in an era when typography is reaching a brilliant end to its career, at the dawn of the new means of reproduction that are the cinema and the phonograph.”

Subtitled ‘Poems of Peace and War 1913-1916’, and dedicated to lost friends, many of the poems in Calligrammes deal with Apollinaire’s wartime experience as an artilleryman and infantry officer. We thought we’d take a closer look. It’s all in French, so we’ve provided translations alongside the originals, and brief analysis of three of his calligrams here.

Influenced by the Chinese ideograms he discovered in 1899, Apollinaire wanted to reconcile form and meaning, the visual and the intelligible. Before choosing to call his collection ‘Calligrammes’, he wanted to call it ‘Et moi aussi je suis peintre’ (‘I’m a painter too’), so essential did he consider this fusion of the arts, already practised by his painter friends (Braque and Picabia) who included letters and pasted paper in their canvases.

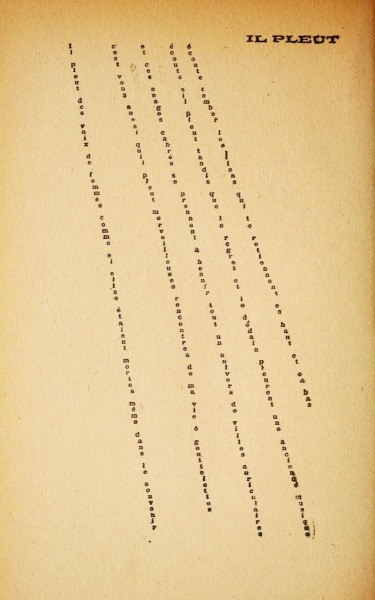

IL PLEUT – IT’S RAINING

Probably the best known of Apollinaire’s calligrams, ‘Il Pleut’ takes the form of lines of words streaming down the page – like rain, obviously. Apollinaire had an affair with a painter called Marie Laurencin. The poem dates from July 7, 1914, when he broke up with her. The lines say:

It is raining women’s voices as if they were dead even in the memory

it is you too who are raining wonderful encounters of my life o droplets

and these rebellious clouds take to neighing a whole universe of auricular cities

listen if it rains while regret and disdain mourn an ancient music

hear the bonds that hold you from top to bottom fall away

From the start, the rain is not a noun but a verb; not physical, but metaphorical. It becomes a vessel for the speaker’s memories of women he has loved, for feelings, for the passing of time. The poem encourages us to listen, not so that we hear the rain for what it is, but for what it might remind us of. The rain carries the past into the present, and – the poem implies – through awareness of its presence one may learn to be free.

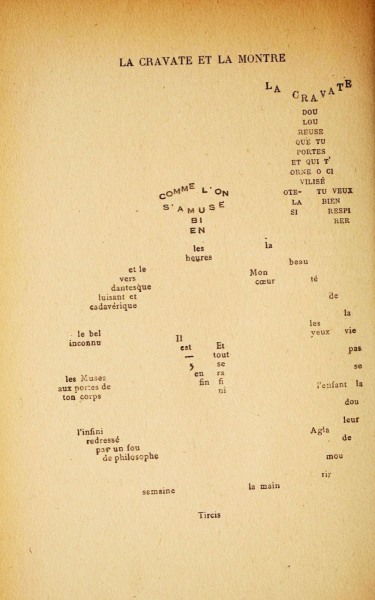

LA CRAVATE ET LA MONTRE – THE NECKTIE AND THE POCKET WATCH

The words in ‘La Cravate et La Montre’ (The Necktie and the Pocket Watch) do what it says on the tin – they form two images, one of a round fob watch and one of an old fashioned neck tie or cravat. Here’s a translation of the text which forms the image of the cravat:

The painful tie you wear and adorn,

O civilized one,

Take it off if you want to breathe.

Here’s a translation of the text which forms the pocket watch:

How much fun we’re having!

Tircis, the beauty of life

Overcomes the fear of death.

My heart, my eyes, the child, Agla, the hand,

The infinite rectified by a mad philosophy

The Muses at the gates of your body

The beautiful unknown

And the gleaming, cadaverous Dantesque verse.

The hours, the week.

It’s 5 at last.

And all will be over.

Serge Férat, the editor of Les Soirées de Paris, where the poem was to appear in July-August 1914, described how these two calligrams came about. Apollinaire loosened his tie and laid it on the table, while Férat pulled his pocket watch from his vest. The calligram became the capture of this moment. The watch and the tie are two objects of ostentation specific to men at the time. The modern man is a man in a hurry; his time is limited; he consults his watch at every turn. The tie is the indispensable accessory of the ‘civilized’ man. The watch is a constant reminder of the anguish of the passage of time, while the tie implies the discomfort of the body.

But this calligram is also a meditation on death, because death (when “all is over”) will free us from the anguish of living. Many sundials bore the inscription “omnes (orae) vulnerant, ultima (ora) necat”: “all hours hurt, the last one kills”. In this way, Apollinaire invites us to become aware of the tragedy of the present, while at the same time delivering to the reader a lesson in practical philosophy, a kind of ‘carpe diem’. Faced with the tragedy of the present, it’s a question of enjoying life, as a good Epicurean, as the wheel on the watch reminds us: “comme l’on s’amuse bien”.

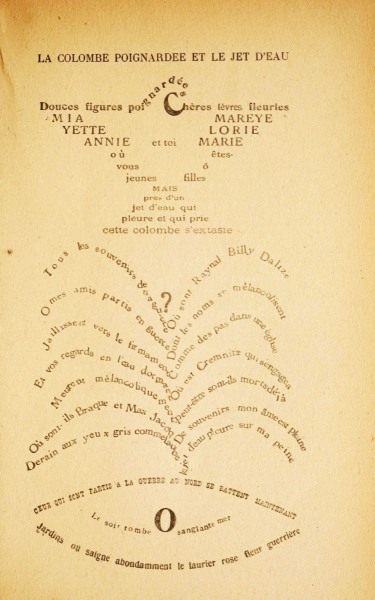

LA COLOMBE POIGNARDEE ET LE JET D’EAU – THE STABBED DOVE AND THE JET OF WATER

Here’s a translation of the text:

Gentle faces stabbed dear flowered lips

Mia, Mareye,

Yette, Lorie,

Annie and you Marie

Where are you O young girls?

But near a fountain

that cries and that prays

This dove is in ecstasy

All the memories of longing

of my friends gone to war

Spurt to the firmament

And your look in water which sleeps

Melancholy die

Where are Braque and Max Jacob

Derain with eyes grey as dawn

Where are, Raynal, Billy, Dalize

Their names are spleen

Like steps in a Church

Where is Cremnitz who engaged

Maybe they are already dead

my soul is full of memories

Fountain cries on my grief

Those who left for the war

In the North are fighting now

Night falls O! Blood-drenched sea

Gardens where bled in abandon

the laurel rose flower of war

The dove is a bird emblematic of peace and love; this one is stabbed, and the theme becomes one of lost love and melancholy, a recurrent theme in elegiac poetry. Apollinaire writes about the women he loved and lost – Annie is probably Annie Playden, with whom he fell in love, Marie is probably Marie Laurencin. The phonic play on first names is also important in elegiac poetry, where the music of the text plays a major role.

With the jet of water we move from female to male figures: Apollinaire evokes the names of friends of his who went to war, including the painters Braque and Derain, and poet Max Jacob. The drawing of the water jet suggests both a vertical, downward movement (“gush towards the firmament”) and a fall (“Evening falls” says the text at the end). But this jet of water can also be interpreted as weeping: “The jet of water weeps over my sorrow”. So in this calligram, the first design evokes lost loves, and the second evokes scattered friends.

The calligram becomes a poem-object: the visual aspect matters. But rhythm and phonics remain the most important elements. Apollinaire successfully reconciles the modernity of his writing with the tradition of an elegiac theme.