Rory Waterman reviews The European Eel by Steve Ely (Longbarrow, 2021)

On the front flap to Steve Ely’s The European Eel, Matthew Gollock (not Pollock) writes: “I remember [Ely] saying how he felt European eels had ‘chosen’ him as a subject – in part due to his name”. We call this nominative determinism, and it is indeed odd how often a person’s job or pursuit corresponds with the name with which he or she has been bestowed: Arsene Wenger becoming the longest-serving manager of Arsenal FC, Bernie Madoff running the largest Ponzi scheme ever, Boris (as we are encouraged to refer to him) consistently proving himself to be a Johnson, with a Johnson that should have got him in a lot more trouble than it has, because he is as slippery as a proverbial eel.

And I have digressed already. But this is somewhat in keeping with the book in question, which weaves in and out of its ostensible subject with eel-like acuity. In three parts, it imagines an eel’s birth in the Sargasso Sea and journey to the Yorkshire pool where Ely captures her for a summer, and then her route back again to the spawning ground. The poem, all fifty pages of it, is in loose blank verse: not metrical, quite, but faltering around five-stress lines, in a manner reminiscent of many of R. S. Thomas’s earlier poems. The effect is frequently frenetic:

[…] billions more

track east along the Channel, in the rumbling

diesel effluent of the ‘busiest sea lane in the world’,

its freight of towering container ships,

the rise and swell of Afghan refugees.

Onward they flow, making five or six miles daily;

over Hurd’s Deep – where the MoD

dumped its phosgene shells and plutonium-239 –

and the paleo-valleys and fossil meanders

of the Weichselian Glacial Maximum.

In the Wreckage of Dunkirk and 1588,

they bury themselves among pieces of eight

and the little boat bones of drunken sailors.

“I’m making it up as they go along”, he writes later in the poem: “Almost nothing demonstrated, almost / everything inferred”. Indeed, we have thus far learned little about how European eels behave in maturity in the wild – and I know this because Ely tells us in a copious section of notes at the end, which also help us to make sense of some of the poem’s more esoteric references. In any case, human lives are happening around the eel and her coincidental fellow travellers without being aware they are doing so. And as the ever-dwindling shoal pushes its way up (and eventually back down) the Humber, Don, and a series of ever-smaller tributaries, in frantic, semi-submerged counterpart to Alice Oswald’s bucolic if uncompromising Dart, the “survivors persist” despite significant despoliation: “blue shit seeped from chemical toilets”, “grey froth of used condoms and sanitary towels”, “Nitram, Roundup, / Viroxide Super, Supalyx Equine Mineral Lick”. Eventually, they find cleaner water, where they wait “buried under banks, in the clefts of rootballs, / wherever the beck finds a yard or so of depth”, including the specific star of the show, who “knots her tail / in the crevice of a rootball and pokes out / her gape in a predatory billow of breathing”.

From the Don to the A1(M), Ea flows

in its V between flat-topped mounds

dredged and piled by long-arm Komatsu crawlers.

The silts are dumped to dry out in the sun,

with their writhing collateral of suffocating eels.

In the filth and smashed flag, under squalls

of gulls and chancing crows, the survivors persist

in their straggling ascent, labouring the shallows

between moated Tilts and the ruin of Bentley Colliery,

its unpumped workings black with coal

and seams of dungeoned eels. What species

will they become there? What have they become

already—the legend of the Bentley Worm,

roaming the anthracite bowels of the earth

starved on the firedamp ghosts of miners,

emerging each Walpurgis Night from the depths

of the Welfare pit-pond, seizing tribute

from the ranks of the High Street’s drunks

and the graveyard’s coked-up, shrieking children.

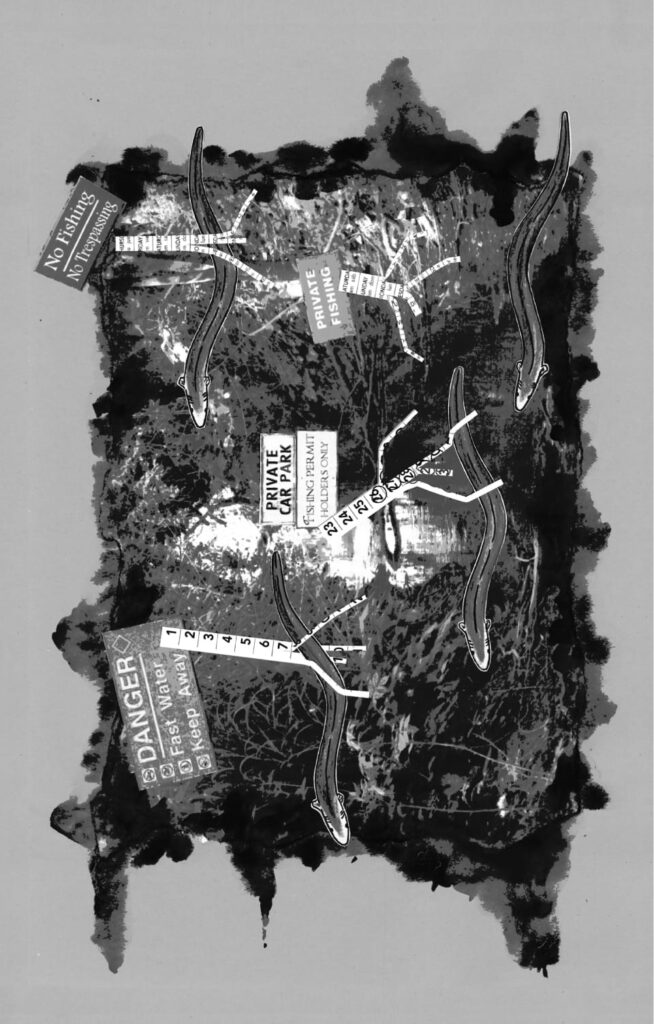

Artwork by P. R. Ruby

The poem’s short metapoetic middle movement is a pause for breath in prose, an account of taking custody for the purposes of what we might call ‘poetic inquiry’ (and what Ely’s managerial apparatchiks at Huddersfield University, where he teaches Creative Writing and which he thanks for a ‘small research grant’, might term ‘a research output’): “I tipped her in, and watched her circle in whiplash panic the walls of her glassy cage. ‘Just for the summer’, I told her. ‘Just for the poem. You’ll be back in your pool by autumn.'” Without labouring his point, the speaker invites us to consider our unwelcome intrigues, and attempts to bring us eye to eye with a being we can never understand, whatever we might know: “I was nothing but a heretic cormorant, one that toyed and would not kill, unaccountably parallel with her living.” The third part of the poem then returns us to the form of the first, and follows the eel back out on her onward journey. The poem is again in the third person, as she shoots “from the H&B culvert like a cork”, out into the swell, and eventually back to the wide Sargasso where the life cycle begins anew with

[…] gusher

after gusher of glittering golden ova,

sparks from the cornucopian flame

of Archaea’s unkillable, dark pleroma,

quickening though the mist of sperm and rising

through the photocline to join the thermonuclear

microplankton of the drifting epipelagic.

But, I imagine many of you thinking, I’m not very interested in the minutiae of an eel’s existence, and certainly don’t want to read an entire book about it. Poetry doesn’t work quite like this, though, does it? We turn to poetry, those of us who do, in part because of the euphoric quantum leaps of semiotics a good poem might cajole our brains into making. The mind’s eye can do things the body’s eyes cannot. The mind’s eye can be given a fleeting glimpse through another – even a very other – mind’s eye. Ely’s command of image is such that he can achieve this, and often does, as above.

… engrossing, fevered, and rich with image, allusion, truth, and imaginative fabrication

In Ely’s native Yorkshire, and as a guest of the poet Matthew Welton, I recently attended the ceremony for the Laurel Prize: ‘an annual award for the best collection of nature or environmental poetry to highlight the climate crisis and raise awareness’, as the prize’s website puts it. Simon Armitage introduced proceedings, and told us how important he thinks the award is; Seán Hewitt won with his celebrated debut collection from Cape. Ely’s book was published at almost the exact cut-off point for this year’s shortlist, might be eligible for the next, and would be a worthy winner. The way things are at present, that certainly won’t happen: he is one of the country’s several perennially overlooked poets who doesn’t deserve to be, a true original with a voice and a mind all his own. At fifty pages, the poem in places feels too long, and yet it remains engrossing, fevered, and rich with image, allusion, truth, and imaginative fabrication. It does not need them, but is accompanied by seventeen pleasingly ethereal full-page monochrome artworks by P. R. Ruby: on one, a map of the Humber is laced with a huge eel and trees and wind turbines apparently constructed from calendars and tape measures; on another, a lattice of pale eel stencils rubs out the background murk. This is an attractive, odd, fulfilling volume.

Read Body of Dark: on writing ‘The European Eel’ by Steve Ely on the Longbarrow Press blog

Rory Waterman is the author of three collections from Carcanet: Tonight the Summer’s Over, which was a PBS Recommendation and was shortlisted for a Seamus Heaney Award; Sarajevo Roses, shortlisted for the Ledbury Forte Prize, and most recently Sweet Nothings. He teaches English at Nottingham Trent University, has written several books on modern and contemporary poetry, and co-edits New Walk Editions. Rory Waterman’s website is here