Charlotte Gann reviews When the Swimming Pool Fell in the Sea by Carole Coates (Shoestring, 2021)

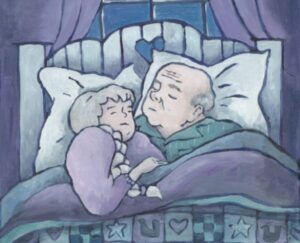

This is the kind of poetry where I lose sense even that I’m reading. The language and imagery are so smooth and seamless, transporting the reader invisibly into the room of the poem. Carole Coates’ beautifully-titled collection is ‘In memory’ of her husband, ‘John David Coates / 1943-2020’. It’s hard for me to imagine a more immersive memorial.

The poems are uncluttered, or perfectly cluttered, with exactly all they need to hold, as they softly introduce us into this home, this situation. The poet’s husband John is ill. And the two are living alone together with this in their home. In the opening poem, with the lovely long title ‘We were talking about the painter who destroyed his work because it did not “trap reality” but merely illustrated it’, we have:

and you replied this is the thing itself

this room and us and now

And so, we are included, folded into the world of this book. The second poem is the first in a sequence of ‘Crazy Days’. I found them tremendously moving, charting life inside this situation. The first poem, for instance, cataloguing how ‘you can’t remember why I left the big bed / in the crazy days’, also sweeps back effortlessly to ‘our first bed – / under the window that looked to the orchard’. These poems are addressed, intimately, to ‘you’. They’re layered with meaning they trust rightly the reader will pick up on.

It’s hard for me to imagine a more immersive memorial

Each of the poems shows us more of ‘Our circular numb life’ (from ‘Crazy Days 5’). Here, from ‘Crazy Days 4’, out and about:

Even in the Christmas queue at the post office

when you convulsed and cried Oh God Oh God

no one turned their heads they were so English.

We get acquainted with key features of the house: John’s ‘great Edwardian desk’ (where later, his ashes sit). That clock – ‘the slow tick tick of the long case clock’ (brilliant!). John’s chair – where, also in ‘Crazy Days 6’ he’s ‘fallen asleep’, and the poet notices how she watches, and feels his body, attunes with it, just as she did when they were younger lovers.

In ‘Crazy Days 8’, someone makes a chance potential diagnosis, which the poet then rolls round and round in her brain,

until those jagged unkind syllables

became a place –

a featureless dark plain

continent-wide and no-one there but us

I feel the aloneness of this image – and that’s really what these poems do for me: invite me into a space where there are only two other people, and later only one. It’s a privilege.

Or this, from ‘Crazy Days 9’:

I said you were doing fine, having lots of tests and they’d soon

find out what was the matter. And I was fine, thank you.

But it wasn’t soon and I wasn’t fine and the only day I cried

I was like a burst main and I drove on the flooded roads

through the rain in a car full of tears.

I find the sheer clarity of the writing stunning. The poet knows which images to pick and share, and notice. These speak volumes so naturally, catching the edge of emotion, and all while we’re simply walking round the house with her, or driving back from the hospital.

‘Part Two’ of the book opens with the poem ‘The window cleaner and life everlasting’. The first couplet is so gentle, and such a gentle way to break the news to us, now, too:

Then the window cleaner said you’ll be missing John

and he would miss him too although he didn’t say that.

There’s another couplet I want to share from that poem – again, an example of how deftly this poet pinpoints her husband’s character:

Both quiet men discussing without argument or rancour

important matters. This would happen under ladders

How I love those rhymes too: the tender matters, happen, ladders. Really, really gentle and beautiful.

I find the sheer clarity of the writing stunning.

And so we move on, into the latter parts of the book, still with this poet, still in this house. This, from ‘Mourning in lockdown’:

and I pace the house go up the stairs down

there was a man once in this house but not this house this replica house

The book does travel, towards the end, and there is much there too to enjoy and appreciate – while of course the dominant theme remains her grief. John’s ‘big grubby gloves for gardening’ in ‘Oh all you dead people’. Or this, from ‘This happened often in the early days’:

I woke crying out Where are you to the late afternoon starting up

from his chair in the stillness

‘Part Three’ broadens or extends the canvas a little – I thought it was genius to take the collection title from a poem here, by the by – and brings more politics, and feminism, and humour too into the frame – wry humour. I was intrigued by the poem ‘Coming back unexpectedly you look through the window at your own room’ – which put me in mind of Raymond Carver’s poem ‘Locking yourself out, then trying to get back in’, and yet was totally different:

the fireplace too its marble uprightness

the glass table that played many games of light

with the sun in the evening and the ceiling

And then the beautiful, final note ‘What we write on stones’, with which I’ll also end. This tender poem has a refrain ‘If I forget you what would I remember’, and contains another of this poet’s perfectly pitched, observed images:

I wanted to go back, read it again

would or should or could

but the river was out on the road

the estuary brimmed and drowned

and set the beached hulks bobbing

What a strong image this is for the inevitability of time passing, stranding us. How I love her choice of ‘brimmed and drowned’, and also, throughout this work, all her syntactical choices, including the punctuation and use of lower case. The poem continues, and ends (with no full stop, I note):

toc toc of a boat’s shrouds against the mast

over there that muddy edge of land

a small mist blown about like spray

an oystercatcher’s one-note cry

Charlotte Gann is an editor from Sussex. She has an English degree from UCL, and an MA in Creative Writing and Personal Development from the University of Sussex. She lived in London for years, working as Editor of Health Which?, among other roles, then moved to Brighton and had two sons. Her pamphlet, The Long Woman (Pighog Press, 2011), was shortlisted for the 2012 Michael Marks Award and her two full collections, Noir (2016) and The Girl Who Cried (2020) are published by HappenStance. She’s a freelance editor, helps on Sphinx Review, and is developing a project she’s calling The Understory Conversation.