Emma Simon reviews What the sheep taught me by Mary Mulholland (Live Canon, 2022)

I have a theory about sheep in poetry: that they are often absent from the poems, and tend to be more symbolic of omission or loss. I don’t know whether it’s the Little Bo Beep connotations, counted sheep melting into oblivion as you fall asleep, or perhaps Plath’s magnificent Sheep in Fog, in which no sheep appear at all (although I often imagine them in the white space around the words, staring back). This theory though is roundly disproved by Mary Mulholland’s excellent pamphlet, What the sheep taught me, published by Live Canon. Although Mulholland is well aware of these references, and plays with them at times, the sheep are very much present, and a striking presence, in many of these poems.

The pamphlet chronicles Mulholland’s time sheep-sitting for a friend on their farm. But this isn’t a beginners’ guide to the nuts and bolts of shepherding – though we do get an insight into the work involved. These are poems that use this interlude to ruminate on past relationships and old scars, alongside present uncertainties. There’s a real sense in the poems of trying to find your way, of being not only out of place but out of time too. I wasn’t surprised to see in the acknowledgements that Mulholland stayed on the farm during the first pandemic lockdown; I think these poems capture the strange way time passed during that period.

I admire Mulholland’s sense of restraint in these poems, and her knack for ending a poem on an open image that doesn’t close down the meaning of the poem. She trusts the reader to do some of the work. We see this in ‘The Binding’, a poem in which the narrator describes clearing barbed wire from the woods with her former friend / lover (who does not seem to be a tremendous amount of help). While the scene feels real and believable, we also read the barbed wire as a metaphor for this relationship: knotty, rusted in places, but with the potential to harm.

I admire Mulholland’s sense of restraint in these poems, and her knack for ending a poem on an open image that doesn’t close down the meaning of the poem. She trusts the reader to do some of the work

The poem describes loops of the untwisted barbed wire being transformed into a sculpture, “the way painful things can seem beautiful”. The poem doesn’t dwell on the significance of this though, but moves back into the narrative of the scene and the friend’s barbed-wire facts. The wire also seems to me to represent the twisted, complex relationship between the man-made and the natural, where we sit as individuals in relation to nature – a theme which is explored elsewhere. The closing image though is both unsettled and unsettling, with a charm-like ‘love me / love me not’ quality:

The rays have made a glade of the wood,

I can see a hare statued among bluebells –

the smell of them is said to cast spells.

The juice of bluebells links love and death.

Last night I dreamt you were dead.

This does not mean I love you.

The construction of those last lines is intriguing. Those end-stopped sentences seem declarative, definitive, but then the meaning we infer hesitates and draws back from any sense of certainty. The narrator says “This does not mean I love you” but as readers we are left asking what does it mean? I found myself combing back through the poem again, trying to untangle the spiky details of this relationship to understand it better. Is the ‘heartwood’ of the trees that the narrator apologises to symbolic of her own heart, or that of her companion? It feels like a dramatic depiction of a narrator trying to work out her own feelings, what binds her, and what she wants to escape from.

‘The Binding’ is a striking poem, and sits opposite ‘The Lyrids’, one of my favourite poems in the pamphlet. This is a beautiful and mysterious poem, full of startling images, particularly concerning the sheep. This seems to be another poem that comments obliquely on the human relationships within the collection, with the narrator heading out at night to try to catch April’s meteor shower, while the ‘you’ is left asleep. Nature is capricious though, and does not always provide what we expect of it. Instead of the “dazzling display / of shooting stars” that should help the “dark to be alive with light” the poet finds stillness among the sheep. I was bowled over by Mulholland’s description of them as they enter the poem:

I flash my torch

over their field ablaze with eyes as if Aries

has fallen to earth.

What a vivid picture! At its heart, this poem seems to be about communication, and how connections can be made beyond language. I liked the way the visual images then merge with sonic ones via the sheep’s bleating and the poet humming to herself. It struck me that this is a good analogy for what a poem should be doing too, melding both to build otherworldly connections between writer and reader.

In ‘The Lyrids’ we catch just the sheep’s eyes, lit by torchlight. In other poems they are often glimpsed partially, but always with deft, well chosen descriptions. In ‘Lessons in Shepherding’ we see the sheep watching the inexperienced narrator “with amber eyes and breath-clouds”. In the moving ‘Still Life’ the ewe has “the eyes of an empress” and her lambs which are removed one by one described as “sculptured alabaster”.

These are clearly not the woolly idealised sheep of the Pastoral. There’s something real about them and they are often far from friendly. In ‘Preparing for Sheep-Sitting’ the lambs buck “like rodeo sheep” kicking, jostling and head-butting. Elsewhere a mother ewe rejects one “shivering” lamb with her “ruby cord dangling”. This un-idealised description of nature is seen throughout – cannibalistic Cream Legbar hens peck and eat each others eggs, crows attack a new born lamb “for the tongue the eyes”, a barn owl kills more than it needs to eat, spewing out what can’t be digested. Elsewhere ragwort grows with “toxic” yellow flowers and even the guardian oak is scarred by a lightning gash down its trunk. This all helps create a feeling of subtle unease that runs throughout the book, framing the human relationships, past and present, which the poems skirt around.

You come away from the poem, and the collection itself, entranced, perhaps like Mulholland herself after her time as a shepherdess, slightly changed by the experience, dreaming of strange sheep

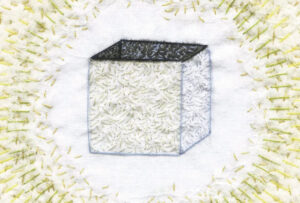

Mulholland is also formally inventive at times. While most are relatively short free-verse poems, it is noticeable that the pamphlet is book-ended by two poems with a more distinctive form. The first is a concrete square poem where readers, like the watchful shepherdess of the title, have to spot the dangers – FOX CROW STRAY DOGS – among the 250-odd sheep.

The final poem seems to draw on the more ancient folkloric elements that are hinted at elsewhere. ‘Hymn to Sheep’ plays with the cultural associations of sheep, lambs and shepherds, and has a haunting refrain, made up of largely (but not completely) unintelligible words. To me this refrain sounded like mis-heard dialect, translated into song. I don’t know what the individual words mean – or if they are meant to mean anything – but set against the invocations to lambs and sheep it felt like a magical chant. You come away from the poem, and the collection itself, entranced, perhaps like Mulholland herself after her time as a shepherdess, slightly changed by the experience, dreaming of strange sheep.

Emma Simon has published two pamphlets, The Odds (Smith|Doorstop, 2020) and Dragonish (The Emma Press, 2017). The Odds was a winner in The Poetry Business International Pamphlet & Book Competition. Emma has been widely published in magazines and anthologies and has won both the Ver Poets and Prole Laureate prizes. She works in London as a part-time journalist and copywriter and has just completed an MA via the The Poetry School and Newcastle University. Her debut collection will be coming out with Salt Publishing in 2023.