Alan Buckley unpacks the poem ‘The Walkers’ by John Glenday

The Walkers

As soon as we had died, we decided to walk home.

A white tatterflag marked where each journey began.

It was a slow business – so much water to be crossed,

so many dirt roads followed. We walked together, but alone.

You must understand – we can never be passengers any more.

Even the smallest children had to make their own way

to their graves, through acres and acres of sunflowers,

somehow no longer pretty. A soldier cradled a cigarette, a teddy bear

and his gun. He didn’t see us pass – our light was far too thin.

We skirted villages and cities, traced the meanderings of rivers.

But beyond it all, the voices of our loved ones called

so we flowed through borders like the wind through railings

and when impassable mountains marked the way,

soared above their peaks like flocks of cloud, like shoals of rain.

In time the fields and woods grew weary and the sea began –

you could tell we were home by the way our shadows leaned.

We gathered like craneflies in the windowlight of familiar rooms,

grieving for all the things we could never hold again.

Forgive us for coming back. We didn’t travel all this way

to break your hearts. We came to ask if you might heal the world.

I picked ‘The Walkers’ as the subject for a close reading for several reasons, the main one being that I think John Glenday doesn’t often get the recognition he deserves, and this is one of his finest poems. But I also think that at a time when many people are writing poems in response to world events, it’s a great example of how to approach that task. Glenday chooses to withhold some key information from the text (an artistic choice I’ll reflect on later) so I’ll try to engage with the poem as I did when I first encountered it, at the very end of Glenday’s most recent full collection The Golden Mean (Picador, 2015). In that context there’s no epigraph or note below the text, only a reference in the acknowledgements section to it having been commissioned to accompany a short film by the Dutch film-maker Judith Dekker. The film, with an earlier version of the poem, can be found here.

John Glenday doesn’t often get the recognition he deserves, and this is one of his finest poems

In Northwords Now (Issue 27) Glenday encourages poets “to begin the poem after the beginning; that politeness, that clearing of the throat”. There’s no preamble here – the opening line of ‘The Walkers’ takes us directly into the middle of a story: “As soon as we had died, we decided to walk home”. At once it’s clear that the poem is being voiced by an individual within a group; the group consists of the spirits of those who’ve died en masse in some unspecified event. And this feels key – I don’t need to know exactly how they died; what matters is their desire to get home.

This opening line also establishes from the off the poem’s relatively informal register – the tone is conversational, the language (in the main) plain-spoken – with a rhythm that is gently insistent rather than heavily stressed, as a shorter, more metrical line would be. Only one line (line 13) comes close to an iambic pentameter, while the longest line (line 8) is twenty syllables long. This lengthening of the line not only quietens the poem’s pulse down to something slightly hypnotic; it also allows entire sentences, or at least complete units of sense, to be much more easily contained within individual lines. This means that where enjambment does occur later in the poem, its impact is significantly heightened.

The first stanza carefully expands my understanding of the journey the walkers must make. It is “a slow business”, with the repetition that follows – “so much water to be crossed, / so many dirt roads followed” – implying a long journey across countries, perhaps a whole continent. In line 2, while I don’t know exactly what a “tatterflag” is, the fact of their being white (the colour of flags of surrender) suggests that we might be in a situation related to armed conflict. I find the closing words of the stanza – “We walked together, but alone” – quietly heart-breaking. The walkers are victims of the same event, but that doesn’t grant them any sense of post-mortem community. I notice I’ve again referred to quietness; although this poem is responding to something horrific, its emotional power is all down to its restraint, its persistent refusal to dramatise its subject matter.

Although this poem is responding to something horrific, its emotional power is all down to its restraint, its persistent refusal to dramatise its subject matter

The opening of the second stanza presents me with a puzzle. Why can the walkers “never be passengers any more”? The poem itself doesn’t answer this, though I don’t experience this as a problem. Without knowing the full background, lines such as this are left holding a sense of mystery; however, I’d argue it’s an acceptable level of mystery. There’s plenty enough in the rest of the poem that delivers an emotional impact with absolute clarity. There then follows a sequence of powerful line breaks: two striking enjambments separated by a line that is sense-ended but followed by a significant qualification. The walkers who must walk alone aren’t just adults; there are children, too, and even they must “make their own way / to their graves”. Their journey is through “acres and acres of sunflowers, / somehow no longer pretty”; “somehow” – in other contexts a perfectly ordinary word – takes on a particularly disturbing resonance here. The last break in the sequence is the most impactful, being not just a line but a stanza break: “A soldier cradled a cigarette, a teddy bear // and his gun”. “Cradled” – with its connotations of a mother holding a baby – inverts our expectation of what a soldier might do, before that expectation is flipped back by “and his gun”. The mis-en-scène of the poem is now confirmed: this is a poem that begins in a warzone, and so I can infer that the walkers’ death was the result of a human act of violence.

The poem then returns to lines that are end- or sense-stopped as it continues the description of the walkers’ journey. It’s here that the language subtly shifts into something more heightened, lending the walkers a particular grace and dignity. The use of simile is, for me, just perfect – spirits crossing borders would unquestionably flow “like wind through railings”. Line 14 contains a pair of beautifully doubled similes to describe the walkers, who rise above the mountains “like flocks of cloud, like shoals of rain”, where “flocks” implies sheep (whose whiteness and fluffiness suggest clouds), and “shoals” implies fish (whose shape and rapid movement suggest raindrops). It’s a mark of Glenday’s skill that such an ambitious layering of images feels utterly natural. So much in this poem is done by ordinary language used in unexpected ways – I love both “the fields and woods grew weary and the sea began” as a way of describing the change in landscape, and the leaning of shadows being an indication of the walkers nearing home. In the final stanza they gather “like craneflies in the windowlight of familiar rooms”, an unassuming but deeply evocative simile. The walkers grieve, of course, “for all the things we could never hold again” – their disembodied state denies them the life-affirming pleasure of tactility.

The opening of the penultimate line always makes me catch my breath: “Forgive us for coming back”. We’re not the ones who’ve suffered a violent death; isn’t it us who should be asking them for their forgiveness? This is followed by the poem’s final enjambment – “We didn’t travel all this way / to break your hearts” – the use of the negative conjuring (as it usually does in a poem) its opposite: hearts, inevitably, will be broken by the walkers’ return. And then the closing sentence, which I think is a textbook example of how to carry off a ‘big’ ending. In keeping with the rest of the poem, the language is plain, unmannered, although as I write this I realise that these ten monosyllables form the poem’s only perfect iambic pentameter – “We came to ask if you might heal the world”.

Glenday’s way of working as a writer is all about paring back, about cutting out unnecessary noise so that what really needs to be heard can sing out clearly from the poem

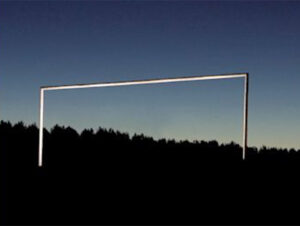

Now for the poem’s full context. In July 2014, not long after Glenday had agreed to write a poem in response to Judith Dekker’s film, Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 from Amsterdam was shot out of the sky over eastern Ukraine; Russian-backed separatists had mistaken it for a Ukrainian military plane. All 298 people on board were killed. The “tatterflags” were scraps of plastic on sticks, placed by locals to mark the location of the bodies; the image of the (rebel) soldier can be found by Googling images for “MH17 toy”. A distinctive feature of this tragedy was just how long it took for the bodies of the victims – two-thirds of whom were Dutch nationals – to be repatriated. There’s no doubt that the poem gains extra resonance from this knowledge, so why not reference it directly? Why not, for example, just use the flight number as an epigraph?

The answer, I think, goes back to the word quietness. Glenday’s way of working as a writer is all about paring back, about cutting out unnecessary noise so that what really needs to be heard can sing out clearly from the poem. Crucially, the fact that he’s writing a poem in response to a major contemporary event isn’t in itself important. While he’s very much a moral writer, concerned with how we relate to each other and the world we live in, he’s not, I believe, a writer who needs to be seen to be responding directly to what’s filling newspapers or social media feeds. Glenday isn’t interested in evoking the intense horror and anger that even the briefest reading around the destruction of MH17 generates in me. His purpose is much deeper than this.

Again and again throughout history, war leads to people dying terrible deaths far from home. The spirits of those who die in this way have an overriding priority: to make their way home, no matter how difficult the journey. But this isn’t simply to find a final resting place. Crucially, Glenday gives the dead an active role in life, which is to confront us with the senselessness of their deaths. The line “we can never be passengers any more” doesn’t just lose its mystery when the context is understood. The line carries a double meaning – the walkers can no longer be physical passengers on a plane or train, but also their experience means they can’t now be emotional passengers, sitting back while the roll call of worldwide atrocities lengthens. And that’s their challenge to us, the living. Are we willing to listen, and consider how we might act to help break the cycles of violence that surround us? (I’m writing this just across the Mersey from Liverpool, where three people, including a nine-year-old girl, have been shot dead in the past fortnight.) Or will we remain passengers ourselves, perhaps expressing our outrage, but then moving on? Are we willing to play our part, however small, in healing the world?

‘The Walkers’ can be read on The Poetry Archive. You can also hear John Glenday reading the poem on this page.

Read ‘Three men found guilty of murdering 298 people in shooting down of [Malaysia Airlines flight] MH17′ in the Guardian 17/11/22