Bruno Cooke meets Santo Niña, the Filipino poet, journalist and activist who uses poetry and social media to give voice to the voiceless

There are two ways Santo Niña keeps her identity under wraps. The first is her name, which isn’t really Santo Niña. Those who intend to educate others about government corruption and foster solidarity among the disenfranchised, whose activism brings with it threats against their personal safety, tend to keep their ‘real’ names under wraps. Shouting from rooftops is ill-advised. This may be especially true in the digital world, where breadcrumbs can be downloaded onto servers, meaning something someone said a decade ago can come back to haunt them.

The second is in ink, or rather, it’s what isn’t in ink. On her left arm are tattoos of some of the things she holds dear: the Philippines’ previous national bird – not the Philippine eagle you might’ve seen in Mikhail Red’s film Birdshot, but a mayang pula, or red maya, a sparrow-like passerine with a brick-red patch on its lower back; a sampaguita flower, also called Arabian jasmine, another symbol of the country; and her favourite, a banana leaf, which represents a ‘boodle fight’, or kamayan. Kamayan is a traditional Filipino hands-on way of eating, from banana leaves laid out on long tables. American military rule, starting in 1898, sought to stamp kamayan out as part of its ‘reform and civilise’ program, making the banana leaf a symbolic middle finger up to oppression – the sort that might’ve rankled those who ruled the country during the first half of the 20th century.

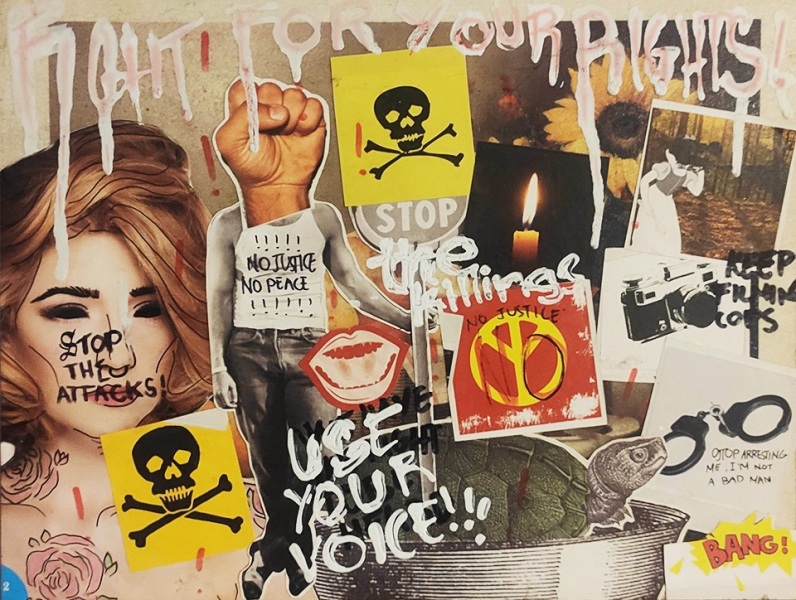

Sometimes, it’s what you don’t see that speaks the loudest

On her right shoulder, meanwhile, is a representation of something that might rankle today, in certain circles. It’s an M16, the kind used by the Communist Party of the Philippines’ guerrilla armies to fight what it saw in the 1960s – and apparently still sees – as the “bourgeois reactionary puppet government”. That’s a quote from the preamble to the New People’s Army’s founding charter. Obviously, there is history to unpack here, and nuance, but suffice it to say that, for Santo Niña, the military rifle she wears is an expression of solidarity. And if it looked like a rifle, it might identify her as a critic of the state. So, for the same reason she forwent the ol’ hammer and sickle (☭), the M16 exists in abstract form, as a series of squiggles and lines, disguised like her name. Sometimes, it’s what you don’t see that speaks the loudest.

Duterte, Marcos, Hitler and a puppy

When she was 11 years old, Santo Niña’s school adviser encouraged her to step up for the role of campus journalist. (For context, the Philippines is big on competitive feature writing. In-school winners take each other on in street-level contests, then, if they’re good enough, divisional, regional and national competitions. It’s a thing. We have them too, though maybe not on the same level.) She was told to ‘describe things’, so she described ukay-ukay, the clandestine importation and sale of cheap, second-hand clothing and accessories. A few years later, she won the national competition, but it wasn’t until university that she discovered poetry, or activism in its truest sense.

There, studying linguistics, she came into contact with Sining Bugkos, an alliance of cultural groups that, among other things, organises the construction, and burning, of massive effigies of political figures for public demonstrations. One, burned in 2017 on the anniversary of the date Ferdinand Marcos placed the country under martial law, was modelled on a Rubik’s Cube, with the faces of (current president) Duterte, (former dictator) Marcos, Adolf Hitler, and a puppy. Another had Duterte cowering behind Trump’s leg like a lap dog (which explains the puppy). It was through Sining Bugkos, which comprises artists, graphic designers, musicians and writers, that Santo Niña first came across what she calls “poets with a niche”, or “poets with purpose”. These are not poets writing for poetry’s sake. They write for the masses. They are protest poets writing songs for the streets, journalist poets writing about how difficult it can be for indigenous Filipinos to get a useful education in the provinces.

These are not poets writing for poetry’s sake. They write for the masses. They are protest poets writing songs for the streets, journalist poets writing about how difficult it can be for indigenous Filipinos to get a useful education in the provinces

The Marcos dictatorship drove NGOs, alternative media outlets and progressive movements underground, or hounded them into nonexistence. Santo Niña tells me that the “crackdowns” that took place under Duterte had a similar effect. The administration that followed his is led by Marcos’ son, known as Bongbong, and Duterte’s daughter, Sara. Manila Today, an alternative news outlet for which she has written, and which has reported on the activities of Sining Bugkos and other activist organisations, was shut down for a period of months, until recently. It’s now back online, but with its archive diminished. Santo Niña says people refer to Duterte as the man with the kamay na bakal, or “iron hand”, and there is the sense that, as the activists burning the effigies, she and her associates are on the wrong side of a game of Whac-A-Mole. When the fist comes down, you run. In the meantime, organise. Write. Spread the word.

Poetry with purpose, but that comes with a price

And so it was that poetry became, for her, an extension of her activist journalism. Whereas long reads and documentaries take time and energy to consume, Santo Niña aims to “catch their attention in just three stanzas”. There is strength in smallness, and in the social media era, a small poem can travel like an Internet meme, or like the humble, pocket-sized zine, which is another format she’s working towards. She’s written about political imprisonment in a poem called ‘Ina’; riffed on the notion that life is so short as to be represented by a dash on a gravestone; and praised the puki – the Tagalog slang for ‘vulva’ – for being the source of all life. Since the point of her words is to raise awareness and give voice to the voiceless, accessibility is key. Therefore she writes, for the most part, in Tagalog.

It comes with a price. Santo Niña has been trolled and followed, and even had her life threatened via text message. She’s relatively nonchalant about this, but also encouraged by the feeling that, by stepping into danger with her writing, she joins a tradition (somewhat ironically) much vaunted by the Philippine establishment. This country’s national heroes include José Rizal and Andrés Bonifacio, radicals who, in simple terms, died for their efforts in fighting colonial oppression. Rizal was a nationalist, author and polymath – he spoke 22 languages – who spent his adult years advocating for political reform for what was then a Spanish colony. Bonifacio was the “Father of the Philippine Revolution”. He co-founded the Katipunan, or KKK (not that KKK), which sought independence from Spain through armed revolt. Their names are hard to avoid as you travel around Metro Manila. Rizal has parks, monuments, a medical centre, a university and a whole province named after him. Bonifacio, perhaps ironically, has what is now Bonifacio Global City, one of the more bourgeois areas of the National Capital Region.

Santo Niña aims to “catch their attention in just three stanzas”. There is strength in smallness, and in the social media era, a small poem can travel like an Internet meme, or like the humble, pocket-sized zine

The parallels between Rizal and Santo Niña are especially strong. Rizal’s novel El filibusterismo, or The Reign of Greed, was banned in some parts of the Philippines for its portrayal of the Spanish government’s abuses. He died by firing squad in 1896. Rizal’s poem ‘Mi Ultimo Adios’, penned in the days before his death, played a direct role in convincing the US Congress to enable Philippine self-government. His last words, incidentally, were those of Jesus Christ: consummatum est – “it is finished”. When the Portuguese-born conquistador Ferdinand Magellan reached the Philippines in 1521 and arrived in Cebu, he gifted the local chief an image of the Holy Child, called the Santo Niño – note the spelling. The artefact is now a cultural icon; its name is synonymous with Christ. The poetic finish, to put rather a fine point on it, is that the name ‘Santo Niña’ suggests something along the lines of a Second Coming – except as a She, and of Rizal rather than Jesus.