D.A. Prince reviews Rock, Bird, Butterfly by Hannah Lowe (Hercules Editions, 2022)

Sometimes a pamphlet is the perfect length for its subject. Rock, Bird, Butterfly is short enough to read at one sitting, with the close-knit poems in a dialogue that gives a satisfying depth to the whole. When a group of poems are ‘about’ a subject – Chinese wallpaper, say, which is the focus of this thirteen-poem set – then to have them fitting comfortably in your hand works well for the reader. The impact of poems like these might get diluted within the more extensive range of a full-length collection. Here, each poem makes its own contribution to what becomes a more complex and conflicted subject, historically and in the twenty-first century.

Most of us, I suspect, will have a nodding acquaintance with Chinese wallpaper and a hazy sense that it was fashionable in the larger stately homes in the eighteenth century. We might retain a vague sense of birds and flowers and, because of its age, a sense of fading into a pleasing background. ‘Wallpaper’ is usually a dismissive term; it’s that background stuff we don’t need to dwell on.

Hannah Lowe shows us much, much more. The poems sit between an elegantly-written Introduction (‘Chinese wallpaper: a global commodity?’ by Clare Taylor) and her own Afterword. Clare Taylor, a Senior Lecturer in Art History at the Open University, specialises in interiors and decoration. Her five-page introduction gives context and background; it also removes the need for notes or footnotes. I approached the poems not only better-informed on trade, subjects, hanging, colours, and the all-important issue of survival but also ready to consider questions on these, and more. This is where poems bring an academic subject to life.

Lowe’s enthusiasm is infectious. The opening poem, ‘Dazzling Blue’, grabs our attention:

And soon I’m telling everyone I meet

about Chinese wallpaper, the lotuses

and butterflies, peacocks, parakeets,

how there are one hundred and forty known cases

in bedrooms from Perthshire to Powys

and more to be found. I’m raving about curators

and wallpaper restorers, how China

Those seven lines are the first stanza and if you wonder why it ends in mid-air, well that’s how excitement runs away with itself. Fluid, colloquial and racing ahead, Lowe’s style also plays inventively with pentameter. None of the five stanzas is end-stopped. It’s as though she can hardly draw breath in her eagerness to tell a friend – and us – about “tea-clippers, / Guangzhou, the Silk Road, the Empire”. A detail of dense blue wallpaper on the facing page matches the poem. The illustrations, twelve of them, are beautiful: some have no margins (so they fill the page) and the whole pamphlet is printed on heavy, coated paper that replicates the luxury of owning Chinese wallpaper.

… a pamphlet that fizzes with energy. Only thirteen poems but they open up new worlds

Who first started this export trade to provide the status symbol of its time? Was it European economic pressure or Chinese entrepreneurship? There are no clear answers – and ambiguity is always a good area for poetry to work in – and Lowe moves around within this with poetic and intellectual agility. ‘If the Wallpaper Could Speak’ questions what might be said:

Would the phoenix

name who painted her,

the red peonies name

who plucked them?

Those red peonies will appear again (in ‘Om’) and opposite a gloriously scarlet illustration. This poem is one of the fourteen-line poems in the pamphlet and while I don’t want to dwell too much on the variations Lowe used so well in The Kids I think fouteen lines is a length she is naturally comfortable with. Her seven-line stanzas are, of course, a part of this pattern too.

Historically, Chinese wallpaper was about money and the display of wealth.

Anyone who was anyone had to have

a China room and Lord Penrhyn had two

‘The Mines’ puts the China rooms in the context of where the purchasing power came from – Lord Penrhyn’s slate quarries, and his sugar plantations and slaves. This is another fourteen-line poem although Lowe adds a three-line coda, repeating the key words “slave/slate”, “quarry/sugar”, “slate/money”. I’m not convinced this is necessary; the source of Lord Penrhyn’s fortune was clear from the poem.

One of the more fascinating aspects of the wallpaper – and I can see how it takes over those who become interested – is the hanging of it. If they survived the journey the highly-valuable flat sheets had to be hung and adapted to fit the rooms. ‘The Hanger’ is the voice of Jonah Button, a man who knew the value of his work:

[…] – any wall

is much enriched by Button’s autograph!

And I’ll retire on an income soon –

without the Hanger, there is no China room.

Lowe’s earlier collections have explored her own ancestry and the London life of her Chinese-Jamaican father. ‘The Look of Things’ introduces what, as a child she would have taken for granted:

[…] the sofa

in my childhood home – pink peonies

and pagodas on black satin, a lilac river,

Chinese women in pale canoes. And the embroidered

hanging of songbirds in our living room.

And the Welsh dresser’s display of Chinese spoons.

Childhood shapes taste. “Even now / in Camden Market, I will always buy my notebooks / with Chinesey-looking covers” Lowe writes, letting the adjective show how the once-niche commodity has been changed by mass production. ‘Chinese Wall Hangings’ takes this idea further:

[…] if anyone asked, I called them heirlooms

from my father’s father’s village, from rooms

where workers in the mountain half-light sewed

pink songbirds to bamboo – though I knew

He’d bought them from Soho, from New Loon Moon

or Lucky Foods.

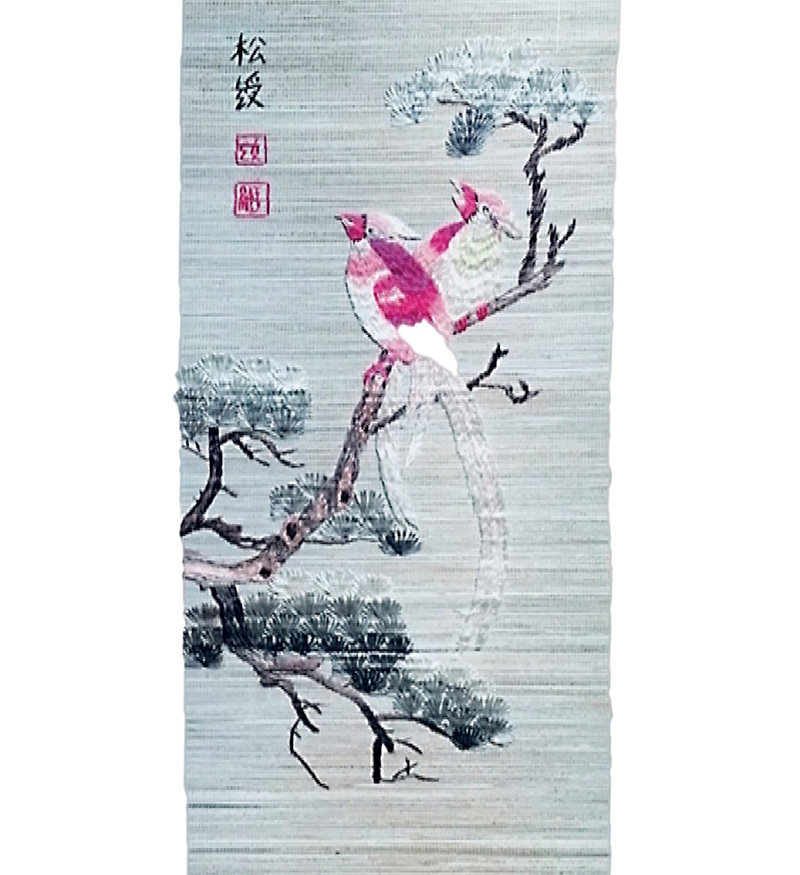

The accompanying photo shows how the elegance of eighteenth-century design has been debased. By contrast the poem shows how much family connections hang on and that there are values other than material ones.

Chinese Wall Hangings

After he died, I took them from his wall,

each with its pair of songbirds: pink silk plumes

and silver beaks. I hung them on my wall.

In Brixton, if anyone asked, I called them heirlooms

from my father’s father’s village, from rooms

where workers in the mountain half-light sewed

pink songbirds to bamboo – though I knew

he’d bought them in Soho, from New Loon Moon

or Lucky Foods. That’s what China was:

two chipped soup bowls, a fire-dragon spoon,

the rack of belly pork he’d string across

our oven spitting fat, a Chinese dress

from Top Shop, and songbirds, factory copycats,

all arranged like a shrine in my tiny flat.

Later, I took the lignum vitae sculpture

from Jamaica – a Rastafarian girl

with smooth swan neck, two twists of plaited hair.

I sat her in the centre of my windowsill

and saw her as my grandmother, from the hills

of Hearts Ease, though we’d bought her at Dunns River

from a higgler banging on the windows of our car.

While Lowe’s four-page Afterword repeats personal background shown in ‘The Look of Things’ and ‘Chinese Wall Hangings’, she’s on new ground when filling in the details of her research. There were visits to National Trust houses at Uppark and Felbrigg, and more academic research taking her to the London Library. Did this commission (from the ‘Colonial Countryside’ project) bring into focus a subject that was already latent in her? She doesn’t address this directly but, whatever the answer, this fusion of family history, love of texture and colour and Chinese design, and her lively curiosity have come together in Rock, Bird, Butterfly to give us a pamphlet that fizzes with energy. Only thirteen poems but they open up new worlds.

D.A. Prince lives in Leicestershire and London. Her second collection, Common Ground (HappenStance, 2014), won the East Midlands Book Award 2015. A further collection, The Bigger Picture, also from HappenStance, is due in autumn 2022.