Charlotte Gann reviews Be Feared by Jane Burn (Nine Arches, 2021)

Jane Burn creates her own language to talk about things. I guess we ‘poets’ all do, in our individual ways, and I love the idea of books creating their own ‘world’ – being a world unto themselves. It seems to me, Be Feared manages this more than most. One poem I really responded to was ‘The First Time I Really, Properly Swim’. Here’s how it starts:

Breathe and timid, walk – fiddle-foot a scree

of greasy rock. I did intend, in shorts to go

(maybe) up to the knee.

Crucially, I find this perfectly understandable – though written in the poet’s really idiosyncratic way. That combination works, for me. I find myself coaxing my mind to relinquish its conventional expectations, and suspend. Here’s more:

Look at my out-spanned crucifixion, shadow spread

along the shimmered hymn. My body brims with wants –

to wear the water’s shroud, silver my bulge,

slip my hulk, re-write myself in rippled ink.

I like the rhymes and alliterations in “shimmered”, “hymn”, “brims”; the “wear”, the “water’s”, the “silver my bulge”, “slip my hulk”, “rippled ink”. I enjoy this: submerge myself in it, alongside the poet.

It’s a book swelling with words – and, at times, feeling-translated-rawly into words

Be Feared is an intense read, and I did need to acclimatise. At times I felt overwhelmed. I certainly found the more personal seeming poems more accessible, for me, than the mythological ones. I appreciated something tangible to anchor pieces written in such exotic language. My instinct, as poet and editor, is to pare back: this work seems counter to that. But the rewards are real. It’s a book swelling with words – and, at times, feeling-translated-rawly into words. I especially enjoyed particular ‘passages’ (I know that’s not a term we use around poetry, but for me, here, it fits) – in, for instance, poems like ‘Aubade to the Noise of Chainsaws’:

I nudge your hillock, slowly breathing still.

Get up. Please. Get out.

There is much I am yet to forgive you for.

On my way through this book, I thought of Under Milkwood, and ee cummings; and novels, a little, like The Bone People by Keri Hulme, for instance, or the work of Eimear McBride. As Burn said in her introduction to the Be Feared online launch, “Every day I find a boundary, and I really enjoy breaking it.”

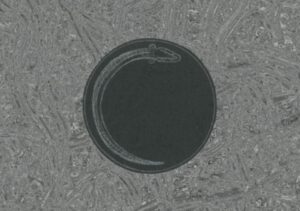

‘The Only Kind of Poetry I Seem to be Able to Write’, among other things, charts life in the womb (I think):

[…] I knew my mother as a tun

and there I grew from tiny round, translucent shrimp, to nix.

I drank. I swam and flickered, pissed and kicked. Was a miracle

for a while. How happy is a body that does not know?

I clung to her warm bank like a glass eel.

My head built a creel of esoteric wires.

How many poets would or could attempt this? Maybe her poems (like Heineken) set out to “refresh the parts other [poems] cannot reach”. She’s especially strong, for me, at conjuring images around the body, and the human experience of being (inside) one. In the second stanza of that same poem, we have “the craving shovel of my mouth”. Or, ‘Fat Alice’, which I think subverts the myth of Alice, reads:

Fat Alice

put her foot in a rabbit hole, fell like a sack of spuds,

almost set her neck. Curious, she says,

cheek on the grass, ankle shrieking, knee dunched,

neck lashed. Curious that nothing

broke my fall. […]

Jane Burn, at times, seems to me to conjure existence as it is for the lovable antihero (I even thought of A Confederacy of Dunces); and then, unashamedly, pours joy and abundance into that flask. The result seems to me a strange and exotic celebration of – perhaps ironically – normal life. (We are most of us, after all, not gods or superheroes, but down in the mud; however ostracised we may feel by all we see in the media around us.)

Jane Burn, at times, seems to me to conjure existence as it is for the lovable antihero … and then, unashamedly, pours joy and abundance into that flask

I liked ‘Aubade to a Wedding Photograph’. And ‘Spun from the Same’, which is a love poem to her son, where the two are sitting on a train, and she’s watching their reflections in the window. There’s also huge love for a foal – a cob – who “tends my loneliness / as if it were an ordinary thing”, she writes in ‘The love that Orca taught me while he grew’. “Together, we have learned / the trick of standing still, my cheek to his sun-warmed back, / his house of a head pressed to the dot of my own.” This poet is also an illustrator, and I can see that in some of these poems.

And then there’s also the other side of the story – the mass of pain. “There is always a wolf” starts ‘Hood’. And ‘So you made a thousand shit decisions’ chronicles a disturbing sexual initiation: “you he said had been broken in”. ‘There are things that give me away if you know how to look,’ has this:

[…] If you touched

me because it was easy / because I do not know how else to be loved /

because I wish I was lovely / because I was lonely / because between

right and wrong are nebulous lines / because you could, then

fuckyoufuckyoufuckyoufuck. […]

I find this very clear, and an important thing to have expressed.

So, there’s a LOT in this book. And often the special language opens doors for me – into ways of talking particularly, as I’ve said, about the body, but also our strange minds, and the relationship between the two. (In the author bio there’s reference to “a late diagnosis of Autism”). There’s much I can join with. I relish, for instance, some of the rich imagery in the poem ‘November’s Spoil of Rain and Plague’, which opens, “I am the daughter of stopped clocks”, and later has:

I am cupboards on uncertain afternoons –

the cube of petrified OXO, the sadly chipped cups.

Allow me to offer my stains.

Overall, for me, I come away thinking this collection brims with: love, pain, body, mind, joy, resilience, and life, including the high price we can pay for it – but, without it, what are we? I like the short poem ‘The Un-flight of Porcelain Birds’ (and indeed that very notion). And as the poet says in ‘The First Time I Really, Properly Swim’: “This, in an age / is the most adventure I’ve had.”

Charlotte Gann is an editor from Sussex. She has an English degree from UCL, and an MA in Creative Writing and Personal Development from the University of Sussex. She lived in London for years, working as Editor of Health Which?, among other roles, then moved to Brighton and had two sons. Her pamphlet, The Long Woman (Pighog Press, 2011), was shortlisted for the 2012 Michael Marks Award and her two full collections, Noir (2016) and The Girl Who Cried (2020) are published by HappenStance. She’s a freelance editor, helps on Sphinx Review, and is developing a project she’s calling The Understory Conversation.