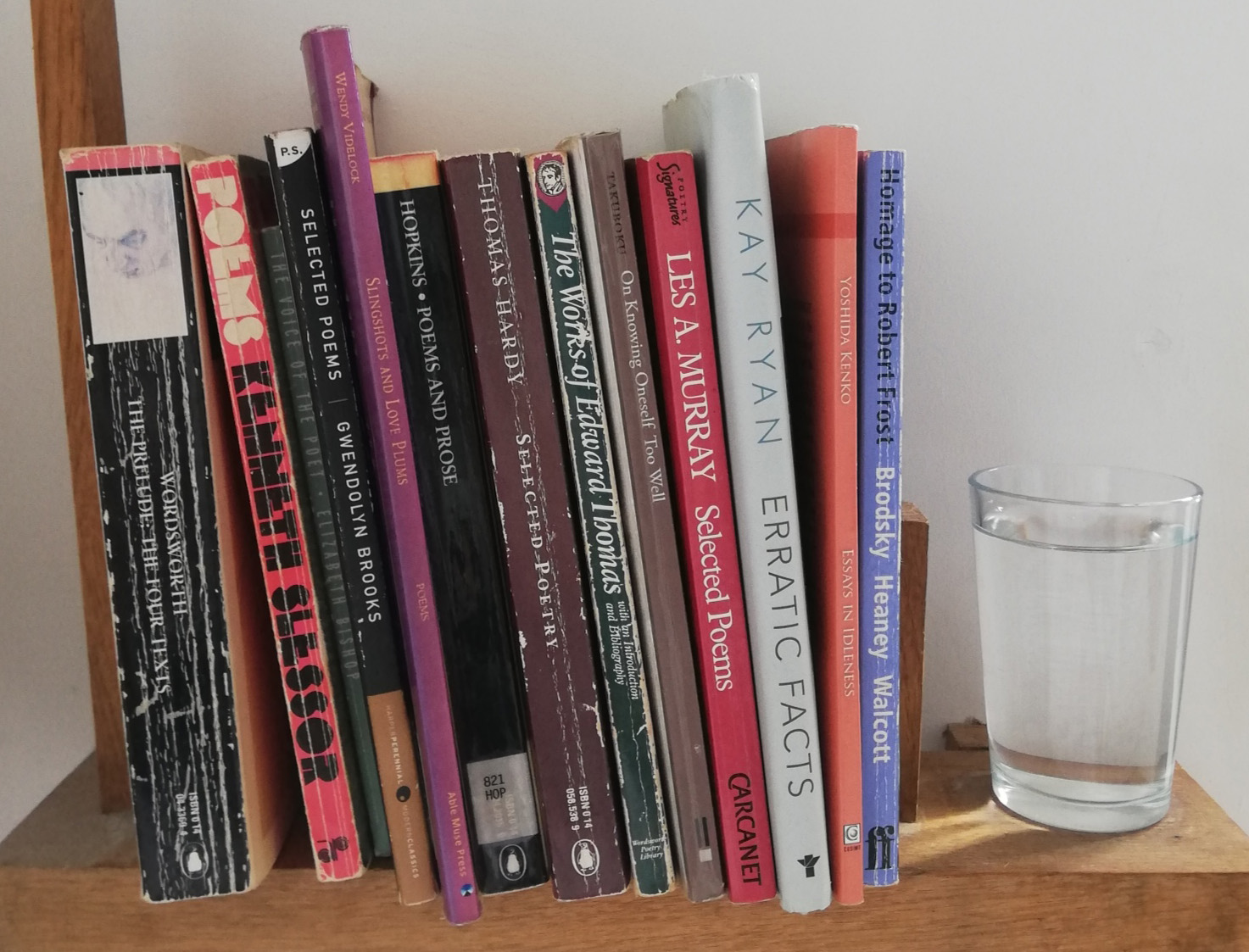

Richard Meier treats us to a tour of his poetry bookshelf

As a big fan of the American poet Kay Ryan (the best poet writing in English that I have read), any piece about those poets I would definitely have on my bookshelf must include her. Her dense, funny, affecting, skinny poems are peerless to my mind. To my ear. I’ve wondered sometimes, though, whether her best poem might just be one she never intended as a poem at all. She dedicated her collection Erratic Facts to her partner, who had died a few years previously. To Carol anyhow, the dedication reads. There’s so much in the music and sadness of this that I hardly know where to begin. It may be that Kay Ryan is such a poet through and through that she can’t help being this astonishing. The vowels. The absolute loss – the defeat – in the anyhow, and yet a sense of ploughing on. It’s just devastating.

It’s a pretty banal thing to observe that all good poets sound like themselves and themselves only. Sometimes it can seem particularly so, as with Kay Ryan. So too with Gerard Manley Hopkins. He even wrote about it, in a way: “What I do is me: for that I came”, he said in a poem called ‘As kingfishers catch fire’.

Nowadays, when it seems as though formal funkiness and political topicality (as opposed to any number of other criteria, such as clarity and sound for example) are the sole markers of what is worth reading and publishing, I find myself thinking about Hopkins quite a lot. In a poem such as ‘Spelt from Sybil’s Leaves’ he wrestled with and smashed open the sonnet form. But as wonderful and strange as his early sonnets are, can one definitively say they are better, more powerful than the Terrible Sonnets of his final years, in which the conventions of the form reasserted themselves? More sensible, more honest, I think, to recognise these poems simply as different.

A poet who I find as individual as Hopkins, but in a quieter way, is Thomas Hardy. I once visited the church in Stinsford, a village outside Dorchester, and which he called Mellstock. The council or the parish council had gone to the trouble of setting up a visitor information board outside the church on which were printed the first two verses of his poem ‘Afternoon service at Mellstock’. In their wisdom, however, they had omitted the third (that is, the bit about doubt and questioning of religious belief). Pretty pathetic but something I imagine which Hardy would have chuckled about, darkly. In those first two rather plain verses Hardy tees us up for the real shock: “So mindless were those outpourings!”. But he’s not done there. No, he’s going to tell us how mindless they were. And then be honest enough to admit to not being

aware

That I have gained by subtle thought on things

Since we stood psalming there.

Perhaps a similar poet next, Edward Thomas. Not showy, at all. Quieter than Hardy I’d say. Astonishing music. Yes. ‘Adlestrop’. Of course. But how about this one too:

Out of the wood of thoughts that grows by night

To be cut down by the sharp axe of light,—

Out of the night, two cocks together crow,

Cleaving the darkness with a silver blow:

And bright before my eyes twin trumpeters stand,

Heralds of splendour, one at either hand,

Each facing each as in a coat of arms:

The milkers lace their boots up at the farms.

There’s something about the finality of that final line which gets me, every time. This is how life is. Night comes, then daybreak. Time and time over. It sounds like the kind of poem Larkin may have had in mind when he wrote Aubade.

Talking about clarity (which I am) then I would have to mention the Japanese poet Ishakawa Takuboku, who died at 26 from tuberculosis. He’s the Japanese Keats and I can’t imagine why he’s not better known here

Talking about clarity (which I am) then I would have to mention the Japanese poet Ishakawa Takuboku, who died at 26 from tuberculosis. He’s the Japanese Keats and I can’t imagine why he’s not better known here. He’s actually my favourite poet ever (I’ve written about him here). Takuboku wrote tanka about childhood, about loss, about illness, ambition, disappointment, belonging. Has anyone ever written a more all-encompassing, more cinematic poem than this?

I picked up a pebble under a walnut tree

At the bank of a river

By a train station of my town.

And what about the pity in this one?

Nothing is more sad

Than to see the children from a country town

Rejoicing over their reunion in a city.

This is a poem which reminds me of Les Murray (e.g. ‘The Burning Truck’). And while Murray is certainly on my shelf, I also think a poet whom he cites as a major influence, Kenneth Slessor, deserves more recognition than he receives. Publishing just around a hundred poems, the Australian journalist and poet Slessor is a poet of great humanity. This, for example, from Beach Burial, a poem about the First World War:

And each cross, the driven stake of tidewood,

Bears the last signature of men,

Written with such perplexity, with such bewildered pity,

The words choke as they begin

A poet from a different age and different continent next – Gwendolyn Brooks. I think of poems such as The Lovers of the Poor, in which Brooks skewers the pieties of the well-off members of the Ladies’ Betterment League, with their loathe-love (what an astonishing construction), as being relatively rare examples of successful writing about inequality and unfairness (you can’t move these days for poems about those subjects, but the vast majority simply want to you to agree with them about how bad it all is – which is not, in my book, the job of writing at all). To me, Brooks has the naturalness of Robert Frost (who, naturally, is in prime position on my bookshelf), with her effortless, easy pentameter:

The worthy poor. The very very worthy

And beautiful poor. Perhaps just not too swarthy?

Perhaps just not too dirty nor too dim

Nor – passionate. In truth, what they could wish

Is – something less than derelict or dull.

With Brooks I have the sense of someone writing authentically. I believe that she knows what she is writing about. I trust, for example, that she knew people like those in ‘The Bean Eaters’, such is the sympathy with which she describes them:

Two who are Mostly Good.

Two who have lived their day,

But keep on putting on their clothes

And putting things away.

To me there’s something Wordsworthian about Brooks’ gaze, her attunement to the needs and plight of the disadvantaged. It’s convincing. I once met a recently published poet who claimed to hate Wordsworth. Somehow I wouldn’t have minded so much if they had been expressing a dislike for Keats or Coleridge, Shelley or Byron. But Wordsworth? How can anyone hate a poet of such vast and subtle sensibility and inclusiveness, who ushered in the modern and gave us all permission to write about the subjects we now all write about? But each to their own, I guess.

To me there’s something Wordsworthian about Brooks’ gaze, her attunement to the needs and plight of the disadvantaged. It’s convincing

A contemporary poet who writes with great authenticity is Phil Hancock. His new book, House on the A34, is published by CB Editions this October. Hancock is a careful observer of people and objects, as I hope is demonstrated by these lines from a poem about some paint-stirring sticks:

I pick one out: holly green –

the last colour it mixed –

clotted, knobbly, glistening,

an accidental Giacometti.

I started with an American, and I’ll (book-)end with one. I don’t know how I came across the poetry of the contemporary poet Wendy Videlock, but I love it. Humorous, profound, playful and triste. Listen to the music in this one. Videlock is a very good and unshowy poet. I really recommend her.

To the Woman in the Garden

You did not notice the roses,

the stones, or even

the toad, the child,

the sapling, the totem

pole, the crow, the dusk,

or the hummingbird,

the mantis, the dove,

or the hushed

word

but spoke instead,

but spoke at length

of the horrible

horrible

horrible world.