Hilary Menos reviews nine by David Harsent (Guillemot Press, 2023)

A beautiful object arrives in the post. It’s a small grey hardback. It has a spine. The front cover is decorated with a black-line scribble of hares and an embossed cursive ‘nine’ in shiny red. Inside it has bright yellow end papers. As with everything from Guillemot, it is beautifully produced – I can feel every penny of its ten quid price tag. And it is authored by David Harsent, who has won pretty much every gong going and wrote Legion, one of my all-time favourite poetry books. So I’m fizzing with anticipation.

nine opens with a note: “What follows is a reconstruction of certain passages from a notebook found among the writer’s effects. Some pages had been damaged, removed or scored out. Gaps in the text are not lacunae: they follow the note-form manner of the original. Nine is a magic number.”.

More of the gaps later, but let’s start with this idea of a discovered text. The first time I came across this kind of thing in poetry it was in Ian Duhig’s poem, ‘Margin Prayer from an Ancient Psalter’ which is supposedly found scribbled in, yes, the margin of an old psalter, and which involves the aside “(Text illegible here because of teeth marks)” and ends “(Text completely illegible from this point / because of lake-water damage and otter dung.)”. I’m sure others have made poems by creating ostensibly found texts, and Harsent himself has played with this trope before, in the first poem in Fire Songs, ‘Fire: a song for Mistress Askew’, where he intercuts the stanzas with quotes from a (real? imagined?) notebook. But to do this at pamphlet length is quite a thing to pull off. Easier, perhaps, in prose. And in fact this book feels more like a short story than a poem, though it is too slippery to call a story, as it is impressionistic and jumpy, full of gaps and implication (yes, more of the gaps soon).

nine opens:

—the riddle of how she came to me at the tideline (of

a sudden in a drift of rain) riddle : tall tale

from some other place : what place? at her sudden

arrival the lost things fell to hand

Is this what this small book is, I wonder, a riddle, a tall tale, a thing to figure out? Bring it on, I say. I’m always ready for this kind of work. But there is the matter of the gaps, oh the gaps. When I see them my heart sinks. This has become such a common tic in poetry, along with various types of non-standard punctuation, multiple slashes and dashes, words scattered over the page to somehow represent what’s going on in the text – oh please no more acorns literally

falling

to

the

ground

and don’t get me started on the problems people with dyslexia often have with justified text. All of these gimmicks – yes, gimmicks – can be a challenge for blind, partially sighted and dyslexic readers, who often need to use a screen reader. A screen reader vocalises certain punctuation marks, implements some, and ignores others, so a screen reader user may experience a poem quite differently from a fully sighted reader. I listened to parts of nine through my screen reader. It paused for some gaps and ignored others, depending, I think, on whether the gap incorporates a colon (most don’t). Also, how long a pause, exactly, does each gap require? My fizz is starting to fizzle. If the project of the poem is to give a disjointed, notey, impressionistic feel then the gaps do do that. But I don’t really see why Harsent is after this result.

So I read the text aloud. I read it with a comma’s beat for each of the gaps. I read it to my husband in the car (he likes it, both the reading and the actual poetry). I read it to my son over supper (he’s not so keen, but he’s had to deal with poetry being read to him for 17 years now so we forgive him). Slowly the sound of the words starts to woo me, seduce me, convince me.

Harsent’s use of language is masterful. He’s an old hand and never fails to impress

Why? Because Harsent’s use of language is masterful. He’s an old hand and never fails to impress. He is audacious in his wordplay and his rhyme, and his imagery is rich, vivid, interesting and new. He has “rags of fog in low branches”. A woman works with knives, and “the shape her hand / makes when she guts a fish describes a fish”. When the woman dreams, “if I were / to read her dream I might find Fool dancing to a sackbut / Fool as putto Fool as maiden aunt Fool playing / ragtime piano in the Chicken Dance Saloon”. And fool can also be found “sitting / on the sea-wall with his two-scoop tutti-frutti”. Ta-dah!

So what is nine about? A woman? It seems so. A specific woman, perhaps, a past lover, maybe:

—the story of herself is simply told. childhood half-

hidden solitary rage unearthly dreamscapes

husband in the usual way skillet stove doorstep

cradle

It is also, perhaps, about women more generally, “their / hands at the skillet pail grate cradle kettle bobbin stove / broom doorstep cradle”, and particularly about those who don’t conform, witches, wise women:

[…] women defenceless against rope

and brand against flame against purge women at

barred windows women lost to themselves women

whose wombs are ransomed

I’d like to be more specific, but specifics are elusive in this book. There are brief descriptions of places, events, physical movements, interactions, but these do not join up to make any sort of narrative. The whole leaves me with more questions than answers. Perhaps Harsent, like the character of the Fool, is using nine to ask questions about “corruption in high places […] about the deaths of children […] about evil and contagion […] about the mechanics of loss […] about how the world has come suddenly to its knees”.

These would certainly be themes familiar to him. His woman picks up a thumbstone from the beach; there’s also a thumbstone (and an inordinate amount of angels) in his recent Dare-Gale pamphlet, Of Certain Angels. Here is a Fool, rats, and the number nine; these also appear in Fire Songs. He has written about destruction, war, and environmental apocalypse. It’s hard to say what ‘happens’ in nine but the end involves broken bones, ash, plague, drought, corruption, “fire-in-flood”, “carnage”, “cities falling”. I’m left with a mosaic of impressions, many of them doom-laden “as when every doorway gives on to a boneyard […] as when a swan is seen to bleed from the eyes”.

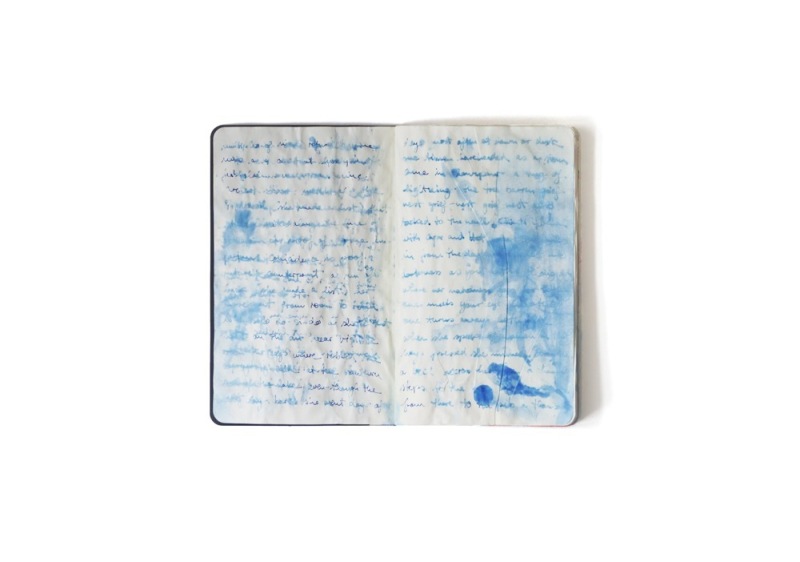

Inside the book there are also eight pages with illustrations by Antonia Glüksman (see two of these above). These show what the found notebook is supposed to look like. They are small illustrations, 4.5 cm high and 5.5 cm wide on pages that are 17.5 cm high and 11.5 cm wide; in terms of page design I wanted them to be bigger, perhaps even to completely take over the actual pages. Perhaps Guillemot or Harsent, or Glüksman) wanted to retain the impression of something in a gallery with white space around, but I think it would have been a bolder choice to go the other way.

When read aloud, nine is theatrical, bold, playful and delicious

In nine Harsent has created a strange and rather fabulous thing. It is loaded with religious and mythological freight – with Christ, angels, women at the foot of the cross, selkies, naiads, hares – and all shot through with the magic number nine. Running counterpoint to this heavy symbolism is the occasional use of ultra-contemporary diction (oddly, most of these words start with ‘p’) – punchline, pay off, pub, marker-pen, Parker Achromatic. He’s particularly keen on two syllable spondaic portmanteau words such as wave break, blood-debt, grief-nest, cloudrace, sound-surge – these sound weighty and charged. When read aloud, nine is theatrical, bold, playful and delicious.

Nevertheless, the cynic in me rather despairs at all these selkies and naiads. And sometimes I feel it is all a bit moonlight and shadow on the darksome tideline; we’ll be in the realms of spindrift next. But I’m from Luton, so you’ll have to forgive me a bit of urban scepticism. For me, nine is a bit like a seven-inch concept single. It’s not the full-length concept double album (there’s fancy artwork but no sleeve notes). I’m not sure that there’s enough to get a hold on to experience the sort of pay-off I want. But if you take it on its own terms – gaps and all – it has a lot to offer.

Hilary Menos is editor of The Friday Poem.