Sam Dolbear and Adam Green look at some 9th century examples of “pattern poetry”

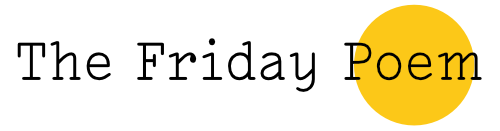

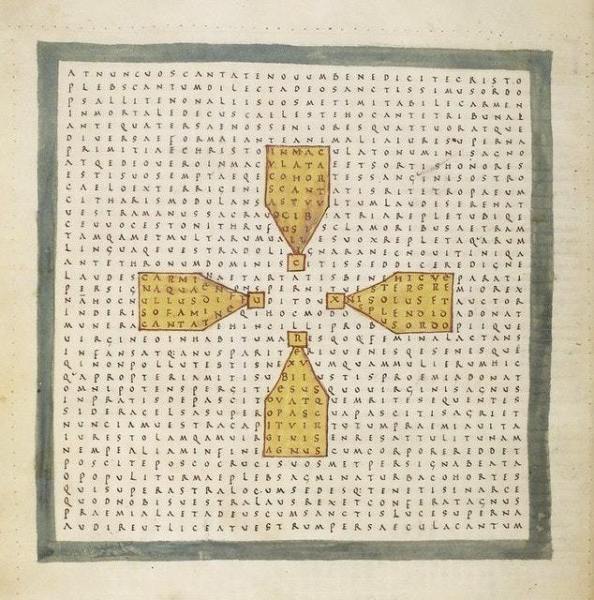

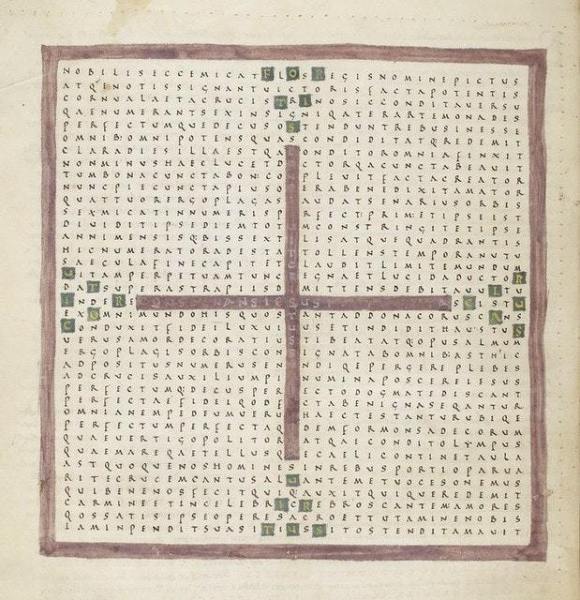

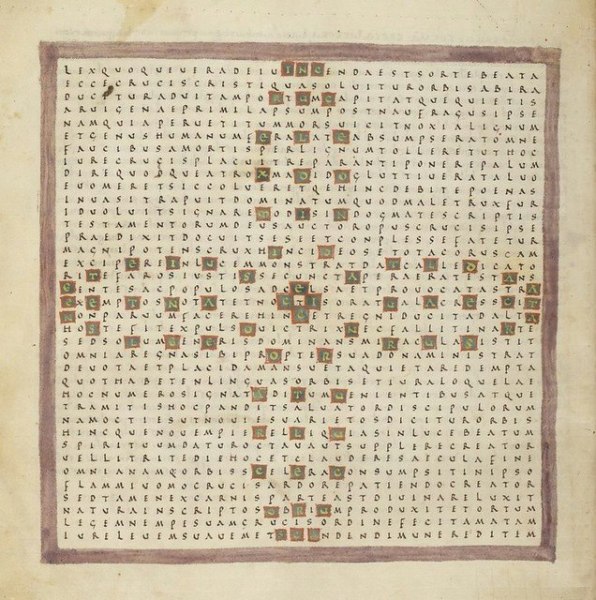

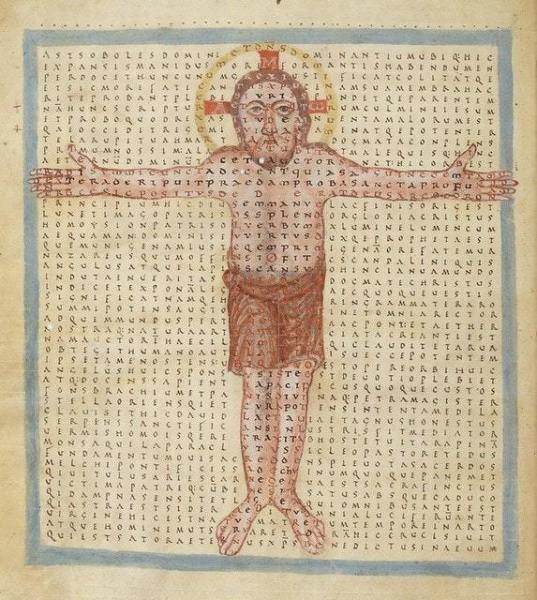

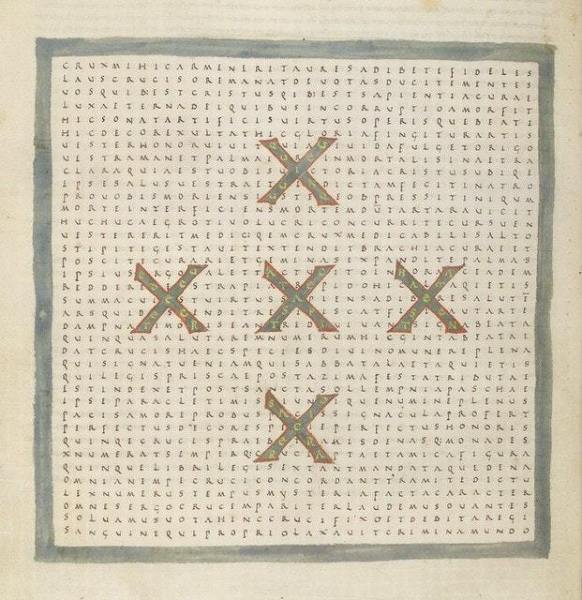

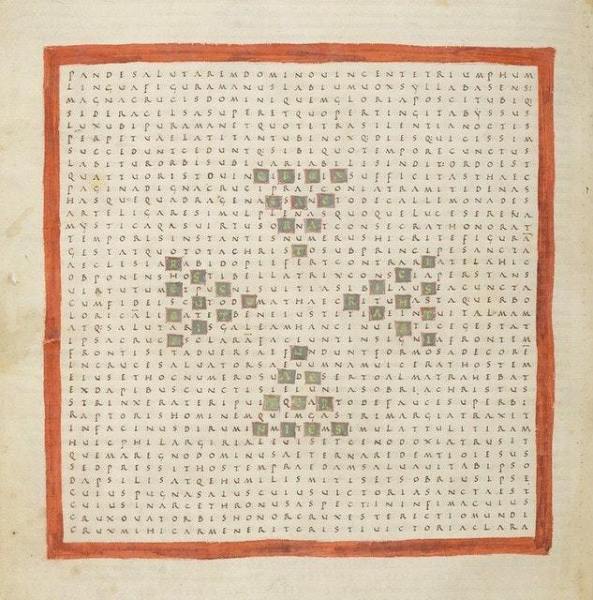

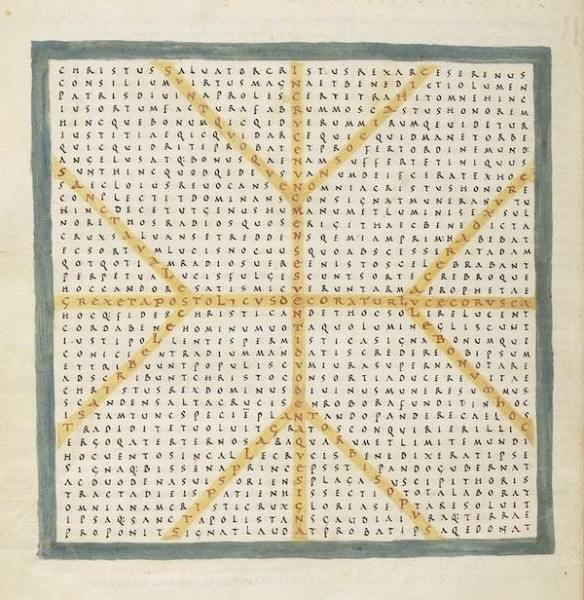

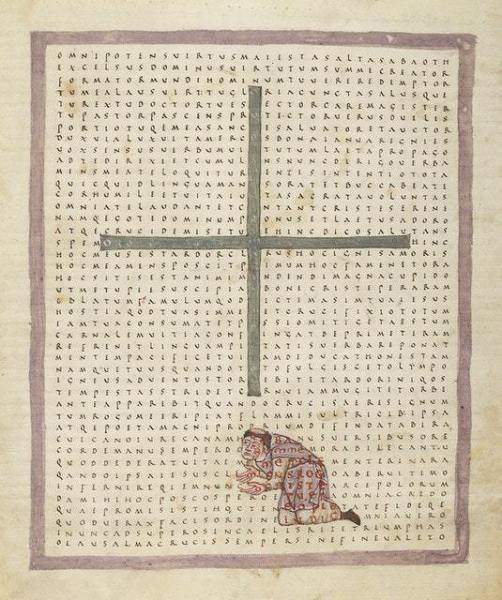

Take a quick glance at De laudibus sanctae crucis (translated as In Praise of the Holy Cross), a ninth-century manuscript by the Frankish Benedictine monk Rabanus Maurus, and you might think you are looking at an elaborate word search or even a medieval knitting pattern. But these spectacular images are actually parts of a devotional poem. Every other page of this unique work contains a poem written out in a grid of letters, a seeming chaos of letters from which emerge other forms: not only new words but figures and shapes too.

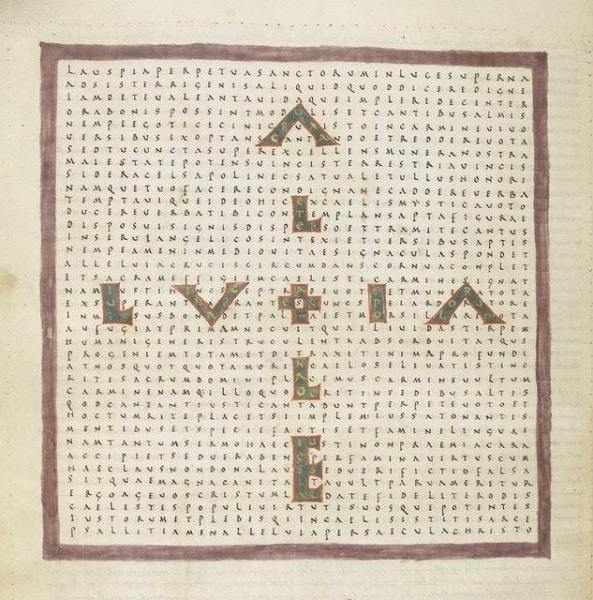

This text is an early case of what became known as “pattern poetry”. In the definitive study of the form, Dick Higgins traces its history to the Cretian “Phaistos Disk”, made in the 2nd millennium BC, in which hieroglyphic text spirals out of the centre, as if it is written on the shell of a snail. The technique took on many different manifestations over the centuries: from Aratea (another 9th-century manuscript), to George Herbert’s “Easter Wings” (1633), to Apollinaire’s Calligrammes (1918), to the poesia concreta movement of mid-1950s Brazil which tied up experimental typography with modernist poetic forms.

True even of its medieval incarnation, pattern poetry has always played with the entanglement between the signified and the signifier, between meanings and their conduits, whether letters or words

True even of its medieval incarnation, pattern poetry has always played with the entanglement between the signified and the signifier, between meanings and their conduits, whether letters or words. But the complexity and ingenuity of how Maurus has interwoven layers of meaning marks De laudibus sanctae crucis as a particularly unique example.

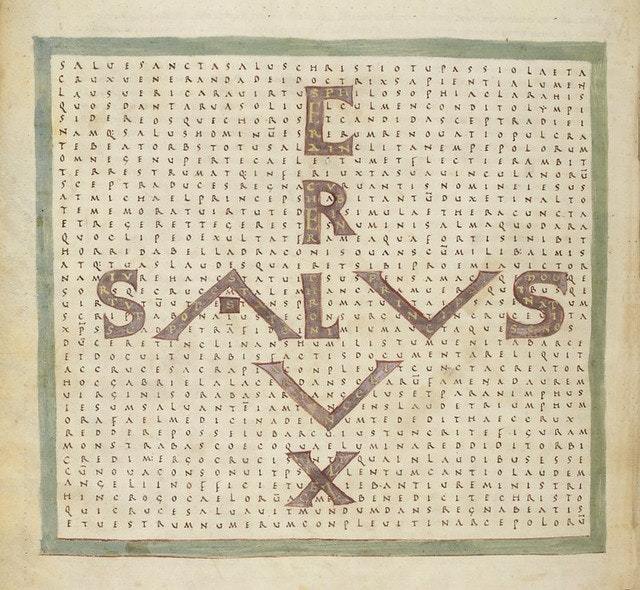

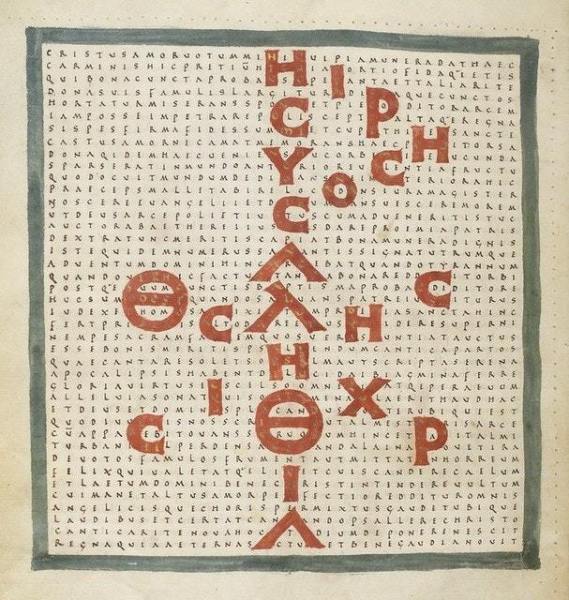

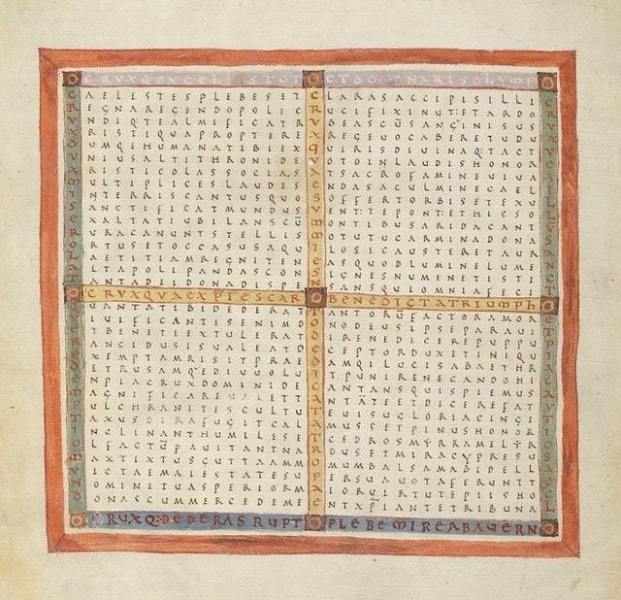

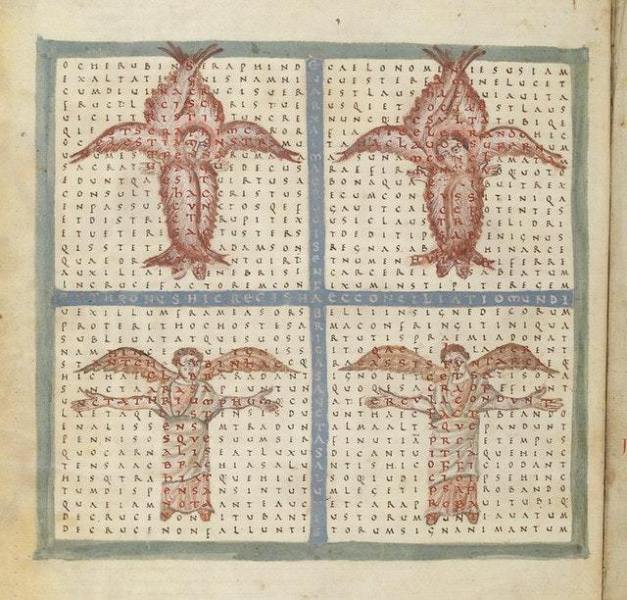

Each grid of letters gives birth to various additional layers, varying in complexity from page to page. Each of these additional forms — be they bodies, shapes, or larger letters — are placed into the grid in such a way as to incorporate and make use of the letters from the grid poem to produce new poems (or at least words or sentences). For example, in one the words CRUX SALUS (The Cross is Salvation) are boldly highlighted from the grid. But closer inspection reveals a third layer here. Each of these large letters itself is comprised of a word: for example, within the C is the word “Seraphin” and within the R another member of the heavenly hosts, “Cherubim”. Both these additional layers (of the large letters and the words within) fail to disrupt the background grid and its sense. It is a remarkable feat of planning and invention.

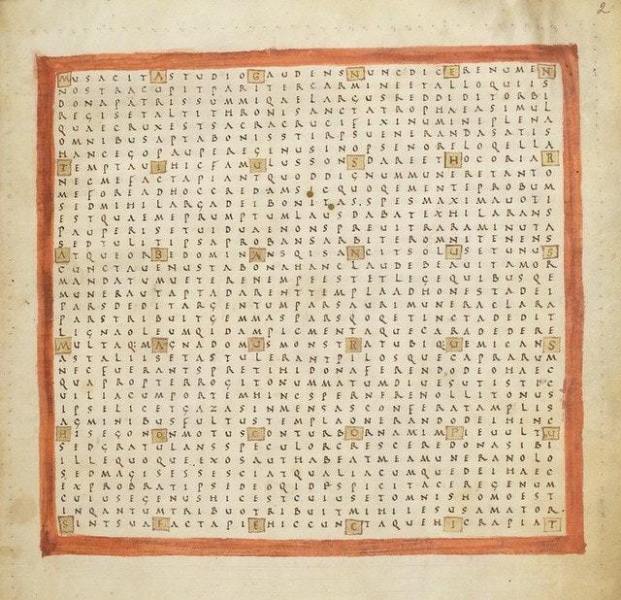

More angels appear elsewhere in the work, new words and sentences spelt out by the limits of their bodies. If angels are seen as envoys or messengers, then Maurus here makes the announcers become their very announcements. Another common theme is geometric shapes, utilised in the majority of the poems, of varying forms but always hinting at a cross in their arrangement. Here Maurus points to a long held connection between geometry, symmetry, and the divine, where shapes reflect a unified order in nature and thus the perfection of God.

Accusations have long been levelled against pattern poetry as an art form

Accusations have long been levelled against pattern poetry as an art form. Ben Johnson dismissed it as “a pair of scissor and a comb in verse”, as the crude prioritisation of form over content. One cannot, however, lay this accusation against the pages of De laudibus sanctae crucis, in terms of its beauty, its devotional care, and the many woven layers of its textual and visual interplay.

Originally composed around the year 810, there are around eighty different copies we know of that survive from the period, a sign that the work was very highly thought of at the time. The images we are featuring here are from a beautiful copy thought to have been done under the direction of Maurus himself and offered to the abbey of Saint-Denis in France between 845 and 847, now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Another notable version is a strikingly colourful copy held by the Vatican from ca. 825. The British Library also holds this 12th-century copy.