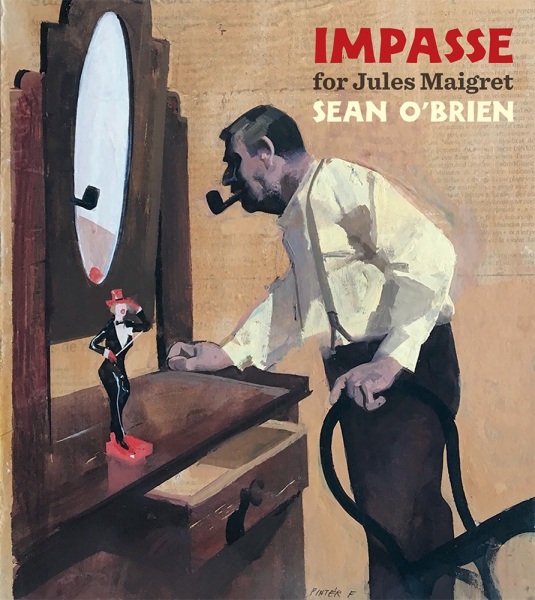

Chris Edgoose reviews Impasse: for Jules Maigret by Sean O’Brien (Hercules Editions, 2023)

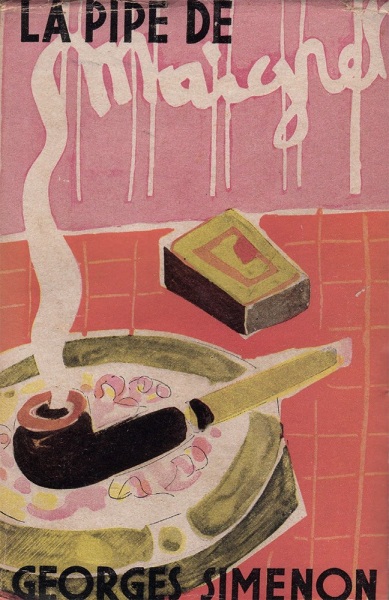

It’s not difficult to see what might have drawn Sean O’Brien to the Maigret novels. In his introduction to Impasse, Patrick McGuinness points out that the world in which George Simenon’s iconic detective exists is one largely inhabited by those Simenon himself described as “petites gens”, and whom McGuinness says we might today describe as the precariat: “people of modest often precarious means, with neither the prestige of the organised working class nor the social standing of the petite bourgeoisie” … “clerks and travelling salespeople, boarding-house owners, cleaners, chauffeurs, barge dwellers, tradespeople”. Compare this list to one compiled by Helen Dunmore in her 2015 introduction to O’Brien’s 2007 TS Eliot and Forward Prize-winning collection The Drowned Book: “The inhabitants of (O’Brien’s) England are withdrawn into themselves. Railway guards, doctor’s assistants, travelling salesmen, artists, convicts, quarrymen, tramps and children, they live in a past that floats just beneath the surface yet can hardly be touched”. You can see the similarities.

The first poem in the pamphlet, ‘Information Received’, is in part another list of ‘types’, characters defined by their profession: “The concierge. The slaughterman. The pharmacist. / The bargee. The cabaret dancer. Twist.” In thirteen lines of couplets, these character-types are imagined to be singing to themselves, and in defining themselves they create the world that gives Maigret meaning: “sing up, my friends, we are the policemen’s choir”. At the same time they suggest why it is that, unlike Holmes or Poirot, there is more to Maigret than locating and punishing criminals; “the facts alone cannot explain desire”.

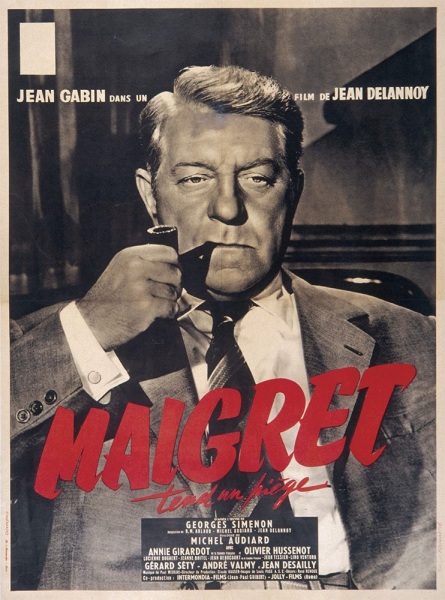

For me, this makes Maigret more profoundly human than his fellow iconic detectives. Of course, the solving of murders is what compels him as a character and drives the narrative of the books, but they are about instances of violence and subsequent sets of circumstances in a particular social milieu, not about the intellectual abilities of the great man who is investigating them. The books are not so much about what Maigret works out as what he sees, and, as O’Brien points out succinctly in his afterword to the poems, “we see what he sees”.

Unlike Holmes or Poirot, there is more to Maigret than locating and punishing criminals

The poems in Impasse emphasise that what we see with Maigret is indefinable because it is human – and the desire mentioned in the quote above is, I think, being used as something like a ‘proto-emotion’ to stand in for all that is inexplicable and yet at the root of what being human is (“rain / also known as desire” he says in ‘Deluge’, emphasising its all-encompassing and inescapable ubiquity).

Impasse, then, seems to stand as a homage to Maigret as an anti-Holmes or an anti-Poirot – a detective who knows (or at least through whom we know) that the solving of a murder is a balm at best, and a form of delusion at worst as it provides a pretence of having brought events to a conclusion. As O’Brien says (again in the afterword), “in human terms there is no ‘solution’, given that the ‘problem’ for those we encounter through Maigret is the fact of being here in the first place”.

Christopher Prendergast wrote, in the London Review of Books in 2007 that “Maigret is different from the heroes of inferential reasoning that populate the genre. His method is not so much cerebral deduction as immersion in a social world and its atmosphere, looking for signs of where and how that world has started to unravel.” It is perhaps this unravelling that in part accounts for the “deep note of melancholia” which O’Brien says he sees in Maigret.

There is more reason for melancholia than that though, as the title poem ‘Impasse’ makes clear. Maigret exists in a world in which there can be no progression, no movement, without death. A train comes to an “unexpected halt at the frontier / between these pages and a roman dur” somewhere in the industrial / agricultural French hinterland, and with it time appears to grind to a stop in the “(r)ain, darkness, the despair of the rational horlogerie” as this atmospheric and richly symbolic scene becomes the eternal prison of the detective genre, because “In this moment it is clear a death / will be required if the journey’s to continue”. But O’Brien seems to be suggesting that this existential blockage is not just applicable to the limited world of the fictional detective, but to real life too (despite the mention of two of Maigret’s ‘faithful four’ police inspectors, Janvier and Lucas, it is by no means clear that the ‘you’ in ‘Impasse’ is Maigret and not the reader themself).

And so again we feel we are in a world of more depth and philosophical significance than the worlds created by Conan Doyle, Christie and others. In some sense, as we read these poems, and the books, TV programmes and radio plays that inspired them, the bleak, rain-soaked landscapes stare back out at us as though they are our own reflection. We are like the patron of the bar Chez Leon in the poem of that name who “stands / transfixed at the tin counter-top / by his own dark face above it / in the mirror with the bottles, // staring back, as irredeemable as coinage / from the failed republic.”

Death being so central to the genre, it is not surprising that it is key to these poems where, as ‘Garagistes’ has it, “only killers and detectives are abroad, / apart, that is, from lovers’ corpses / sprawling in the ditches, with their pitiable candour / anguished in the fleeting moonlight.” (And what a couple of lines! To die for, appropriately). The dead are so much with us that they cannot even properly said to be dead, and they are an attribute of the Maigret paysage, which is – this becomes clearer with every poem – an interior landscape, as much defined by its dead-ness as its living-ness: “and all of this belongs to France / the heart of yellow-grey / long dead and beating still” (‘The Sacred Heart’). The still-living dead, or perhaps the dead within those who are still-living, come up again and again in Impasse – in the barges pulled by “the skeletons of horses” (‘The Sacred Heart’), in “the sleeping town” where the dead “live / in their retirement, modestly” (‘In the Zone’). And these references bring us back again to O’Brien’s earlier work The Drowned Book which had a similar instinct to pull the dead back to somewhere “just below the surface”: “Come for a walk down the river road, / for though you’re all a long time dead / the waters part to let us pass” (‘The River Road’). It might in fact not be out of place to describe Impasse in the same way Dunmore described The Drowned Book, as “a book of the dead”, and to claim likewise that in these twelve short poems, “(the dead) are mourned and elegised, and yet they sit down with us at table as they have always done.”

There is a pleasing intensity to its brevity, and the poems form a self-contained unit, almost claustrophobically so, which is appropriate given the subject

O’Brien is rightly suspicious of reading poetic qualities into Simenon’s novels themselves, but he has, I think, been inspired by seeing the poetic potential in Maigret’s world. Indeed, Simenon has been admired by various literary luminaries of both the past and the present, and his work has even been compared to that of Jean-Paul Sartre (Prendergast noting that “Simenon himself took the even more flattering view that Sartre had imitated his example”). As hinted at above, there is certainly something existentialist both in the original and in O’Brien’s ekphrasis – in fact, the title of the poem ‘Deluge’ has such a suitably biblical feel to it that it could almost sit alongside Camus titles like La Peste and La Chute as an allegory of the human condition (although actually the poem itself, with rain pouring all over Paris, soaking everything and everyone, actually has more of a Joycean feel, bringing to mind the epiphanic snow blanketing everything and everyone at the end of Joyce’s long short story The Dead: “It is desire, when the clock beside the bed is close to death from waiting / and the rain is beating on the fanlight. You will never see it all – the city / with its million needs and sorrows, but you’ll know at least / that happiness is relative.”)

If I have a minor criticism of the pamphlet, it is just that it is not long enough. There is a pleasing intensity to its brevity, and the poems form a self-contained unit, almost claustrophobically so, which is appropriate given the subject. But it would have been interesting to see what shade and light might have been added by a sequence two or three times the length. The poems included set off a lot of interesting trains of thought, treat us to some magnificent poetic turns of phrase, build a quite mesmerising atmosphere in very few lines, and provide an illuminating tool to take into and enhance further readings of Simenon. But they are in some sense a victim of their own success. Having been effectively drawn in, I feel as though there is still a vast dark terrain out there which I want to walk through, but which O’Brien has so far chosen to leave un-illuminated.

Chris Edgoose is a poet and blogger at Wood Bee Poet. He lives near Cambridge in the UK, and has had work published in several magazines in print and online.