Clare Best writes about making opera, “possibly the most intensely collaborative and most challenging of all art forms”

Take Me With You

I met Tim Andrews in January 2013 through Brighton & Sussex Medical School where at different times we had presented our work as part of the Ethics in Performance series. Tim and I had both evolved our very different experiences of medical challenges into creative work, and we bonded quickly.

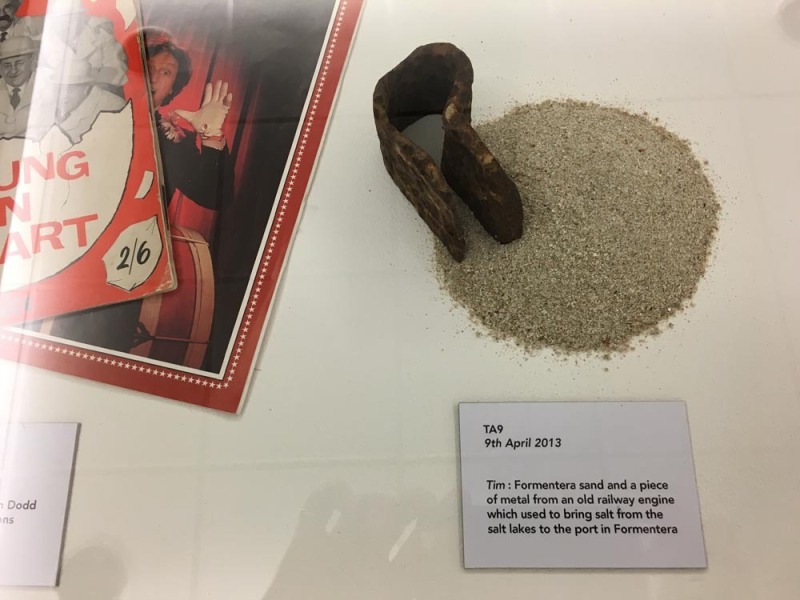

Our collaborative project Take Me With You began with this question: If each of us could choose 21 things to take with us to the next world (whatever that might mean) then what would those 21 things be? Over a period of nearly three years, Tim and I corresponded about our choices and the reasons for them – a dialogue that ebbed and flowed, accommodating life’s demands. This long conversation about memory and mortality led us into friendship.

One end product of our collaboration was The Museum of Friendship, Remembrance and Loss – a single-night display of the things each of us had chosen. This very short exhibition was part of an event at Brighton & Sussex Medical School, hosted by Bobbie Farsides on 18 February 2016. Tim and I talked together on stage that evening about our collaboration, about what the work had meant to us, and about how it felt to display our special objects in a public space. Take Me With You was an invigorating project, investigating how we think about and discuss (or not) uncomfortable truths. Later, Tim made a film attached to the project.

It had been in my mind for years that I wanted to work with composers and musicians, but the publication of my memoir The Missing List (Linen Press 2018) proved to be a watershed in my writing life as well as in my personal life. I knew this was a good time to make a move into immersive collaborative work, do new things.

The Apothecary

In 2019 I was accepted for the Masters in Opera Making and Writing at Guildhall School of Music and Drama. This programme takes three composers and three writers every year and leads them through a rigorous programme of workshopping and creative ‘speed-dating’ before pairing writers with composers. This is followed by months of hands-and-ears-on collaborative working, supported by professionals who know how difficult it is to successfully combine words and music on stage. The main thrust of the year is co-creating a 25 minute chamber opera (written for the voices of the extraordinary singers on the Opera Course) which is then designed, produced and staged by the Opera Department at Guildhall working with teams from Guildhall’s production arts and tech / AV departments.

When the pandemic struck, things had to proceed quite differently from the original plan, of course, but numerous additional tests to our collaborative working probably strengthened our partnerships and our operas, in the end. The Apothecary (the chamber opera with an X-rated poisoning theme, which I made in 2020 with composer Amy Crankshaw) and the other two operas made by our cohort that year, were finally given fully staged productions at Silk Street Theatre in June 2021 – a year late, but all the more exciting for that. Here’s a link to a film of the fully staged production at Silk Street in June 2021.

The Apothecary in production, Silk Street Theatre, Barbican, London, June 2021. Composer: Amy Crankshaw. Librettist: Clare Best. Director: John Ramster. Music Director: Chad Kelly. Designer: Louis Carver. Lighting Designer: Jack Wiltshire. Cast: Olivia Boen, Laura Fleur, Adam Maxey, Thando Mjandana, Laura Lolita Peresivana.

During that Masters year I also worked with composer Alex Mills. Alex was a journalist before he made his way as a composer, and we share a liking for repurposing pre-existing texts, or ‘found texts’. We worked together on Flame Robin, recorded with Exaudi just after the severe bush fires in Australia in winter 2019-2020; I assembled the text from a list of extinct and endangered bird species. Another piece I made with Alex, Testimony, used found texts describing conditions in flooded parts of the Far East around the same time. This, and a ‘mirror’ piece – Mirus – about the polar albedo, made with composer Erchao Gu – were both casualties of the pandemic; they should have been performed at Wigmore Hall in May 2020, but that couldn’t happen. However, I look back with gratitude on these collaborations – I learned so much through widening my collaborative net at that time, creating experimental texts in close association with two composers who have a particularly strong relationship with words as well as music. And in terms of subject matter, I will definitely be working in the future on other pieces relating to climate collapse.

Of course 2020 turned out to be a challenging year in which to extend my practice into writing for performance, but it was exciting to work with so many wonderful and talented composers, singers, instrumentalists and production arts people, not to mention the academics and other staff at Guildhall.

Although it’s possible to learn about which kinds of texts are more suited to being set to music, or the importance of pacing texts for singing, or how patterning and repetition can work hard to convey meaning, or the different kinds of language required by aria and recitative, or the vital aspects of dramaturgy and how they work in opera and musical theatre – certainly, these things and so many others can be learned – the success or not of a piece that combines music and words for stage depends to a very great extent on the viability of the creative partnership making it.

Sounds obvious, doesn’t it?

When it comes to a successful composer / librettist collaborative partnership, making opera or other similar work, the list of desirable features in the partners is long. Here are some of them:

- exceptional creative generosity

- wholehearted trust

- the courage to keep trying things out

- a working knowledge of the job the other has to do (plus of course the desire to acquire that working knowledge)

- a willingness to listen to and accept prompts and opinions in your specialised area from someone who might not have much experience of what your craft entails

- great sensitivity to the pressures and challenges of the other’s craft

- sublime communications skills

- even more sublime timetabling and deadline-juggling skills

- infinite patience

- the facility to talk turkey when things go wrong (which they do / will) and work the problems through, at every stage of the collaboration

- a well-developed sense of when to hold your ground and when to concede it

- the gift of inventing ways to talk across artistic fences – metaphor comes in handy!

And on and on and on.

Also, of course, the collaboration between composer and writer is just the beginning … alongside that there are collaborations with the director, the singers, the music director, etc etc etc, all of which will only really work comfortably if the original dynamic duo have cracked the thing of co-creation.

The libretto (comprising the story, the words and the stage directions) of an opera or related work serves three main purposes:

— The libretto supplies the shape and overall dramatic arc of the piece.

— The words inspire the composer to do their job (most composers I’ve worked with really do draw their imagery and the emotional language of their composition directly from the actual words on the page).

— The words, as delivered by singers in performance, communicate story, characters, plot and a lot else, to an audience. Key words, sentences and passages – once set – should be able to be sung clearly enough to be heard and understood. It is very unlikely that all the words will ever be heard clearly in performance (not least because in opera people often need to sing different lines at the same time) and at the risk of being controversial here, I’ll say that I don’t even think this is especially desirable. If the piece is working as it should, the music will convey much of the meaning at certain moments, but it is vital to know which lines must be understandable and then focus on making those really clear. Subtitles and surtitles are useful but should never become a prop or an excuse for a lack of clarity in the words and singing.

Rotten Kid and TEXT

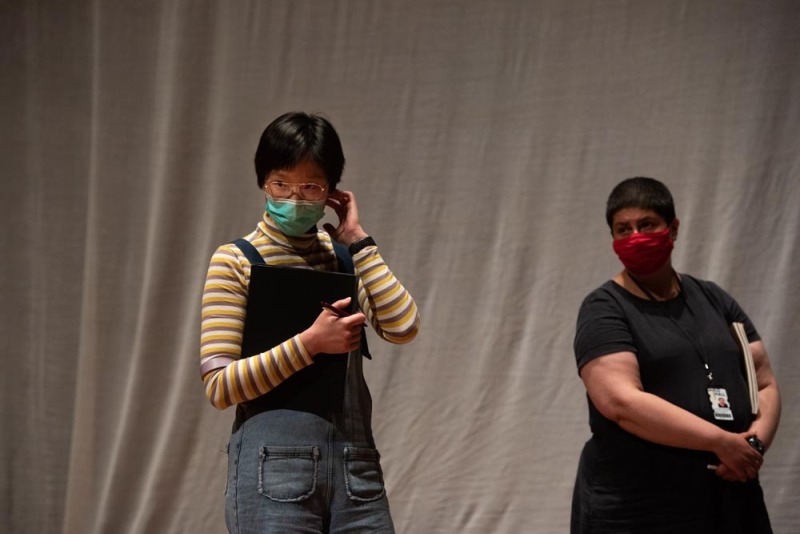

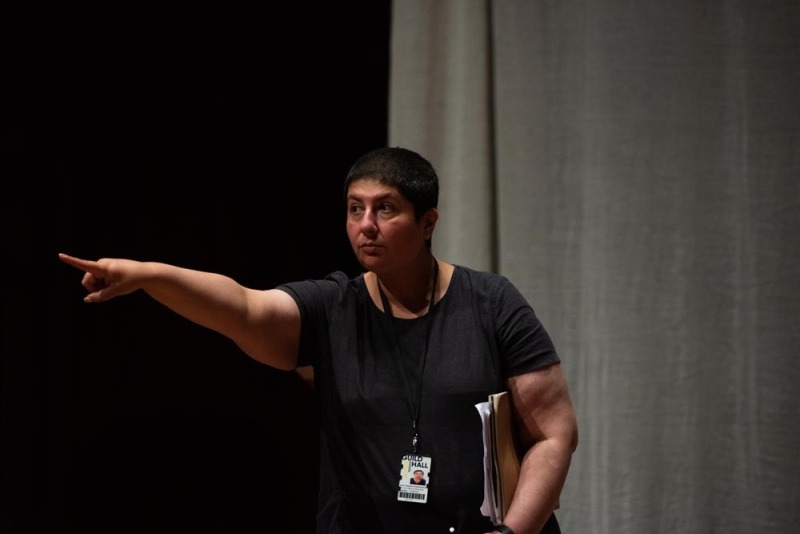

After graduating from the Opera Making MA, I was invited to spend another year at Guildhall as a Junior Fellow, so from autumn 2020 I collaborated on two more chamber operas: Rotten Kid with Erchao Gu and TEXT with Michael Bascom. Because that year started off in lockdown and moved towards more normal conditions (the reverse of 2019 which had begun normally and hit the brick wall of Covid early in 2020) it felt easier to cope, and by then we were all anyway used to doing ordinary and extraordinary – even miraculous – things on Zoom.

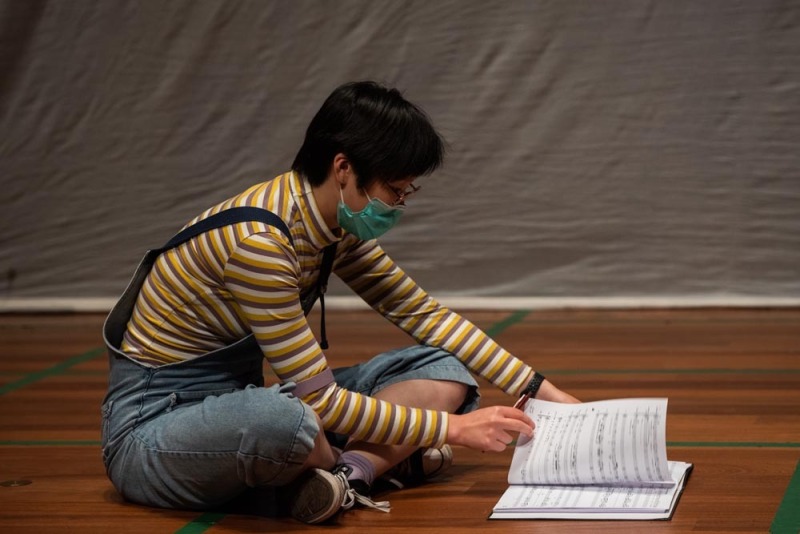

Rotten Kid production photos by Ábel M.G.E taken at the dress rehearsal and showing of this score-in-hand work-in-progress at Milton Court Concert Hall, London on 30 June 2021. Composer Erchao Gu. Librettist: Clare Best. Director: Nazli Tabatabai-Khatambakhsh. Music Director: Victoria Hofflin. Scenographers: Manuela Pecorari & Paola Sanchez. Production & Stage Manager: Paris Linxuan Wu. Cast: George Curnow, Juliet Wallace, Francisco Reis.

I learned a whole lot more about musical collaborations that year, and had the luxury of trying out all kinds of new approaches. Both TEXT and Rotten Kid were staged in July 2021, with their premieres on consecutive nights, soon after The Apothecary had its live run! Never again will I have three operas staged in the space of six weeks. Heady times … and what a steep learning curve.

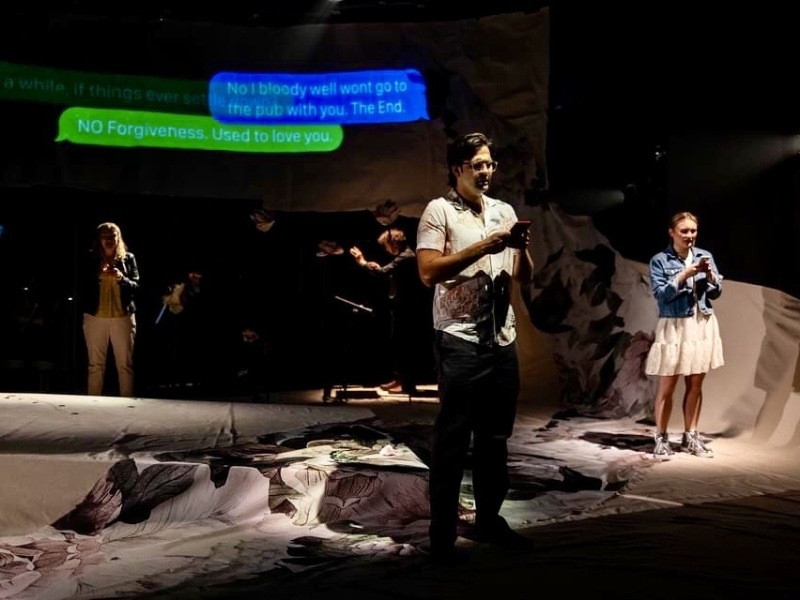

TEXT in production, Studio Theatre, Milton Court, July 2021. Composer: Michael Bascom. Librettist: Clare Best. Director: Martin Lloyd-Evans. Music Director: Dominic Wheeler. Designer: Louie Whitemore. Lighting Designer: Finlay Anderson. Cast: Jack Holton, Amy Holyland, Cleo Lee-McGowan, Ellie Neate, Florian Panzieri.

An additional, and serendipitous, musical collaboration with composer, writer and music critic Hugh Morris coincided with my Guildhall years. Hugh contacted me because he had seen the poem ‘Water Spirit’ (from Springlines) on my website and was keen to set it as a commissioned piece for Ludlow English Song Weekend. He composed a beautiful song, but its performance was another casualty of Covid, since LESW was postponed again and again. By the time the festival was reinstated, Hugh had decided to set three other songs from Springlines and these were performed in Ludlow in October 2021. It was a moving moment for me, after all the waiting, and especially with the strong connection to my much earlier collaboration work on Springlines with the painter Mary Anne Aytoun-Ellis.

I find working with composers and musicians an exciting and liberating field of collaboration. It’s visceral and all-consuming. The work takes a long time to make, and then performance is so fleeting, so ephemeral. This is sobering and refreshing – it’s very real life. You make the work, you make it as well as you can, and you move on. Exhibitions of visual art are performative too, of course, but the ‘performance’ is generally slower, lasting days or weeks as opposed to minutes or hours. Take Me With You – The Museum of Friendship, Remembrance and Loss, the exhibition that Tim Andrews and I put together for one night’s showing in February 2016, was more like a stage show than a conventional exhibition, in that respect.

What I really like about making work with other artists, in whichever artistic area, is how much the work stays focused on process, rather than product. The collaborative product is often, in fact, by-product.

I’ll always make solo work (I think of it as garret work!) and I hope I’ll always make collaborative work too. I need to do both. I’m still figuring out why, but I think it’s partly because when I’m collaborating I feel I can let go of the work along the way, or perhaps not ‘fix’ it until much later in the process. The work, the ideas, remain plastic for longer.

I enjoy the messy, generative soup of collaborative working. I like the adrenalin shots too, from that first surge of excitement right through all the meetings, the workshops, the deadlines, hanging the exhibition, checking the proofs, the rehearsals, the opening night. Plus it’s a bonus that good collaborators can constantly facilitate fresh aspects of creativity in each other, helping one another move out of comfort zones. Then, after the collaboration, each gets to take new skills back to their garret, or on to the next project.

What’s next?

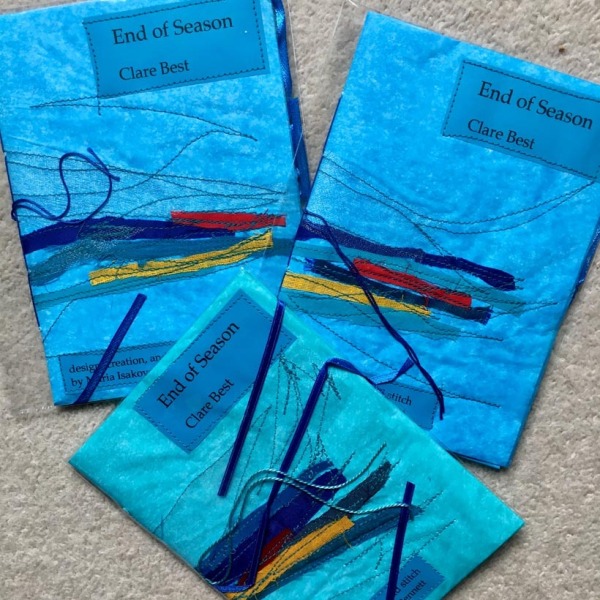

Presently I’m preparing a bilingual edition (English / Italian) of End of Season to be published by Frogmore Press this September. End of Season is a group of fifteen poems inspired by a place and landscape I know well on the northern shore of Lago Maggiore in Italy.

This is a project that has moved from the solo work of writing poems (the garret!) with no particular end in mind, through the realisation that they might in fact need to become songs, to the first publication of the poems with Coast to Coast to Coast in 2021 in a limited handmade and stitched edition by Maria Isakova Bennett through translation of the poems into Italian by Franca Mancinelli and John Taylor, to working on the design of the bilingual edition with graphic designer Katy Mawhood; through collaborating again with composer Amy Crankshaw who is setting some of the poems (in English) as a song cycle, to liaising with the musicians who will perform the work for the first time this October, in the very place that inspired the poems. Every stage of this process has been and is immensely exciting, giving me the powerful sensation that many strands of my life and work are being pulled together in a beautiful collaborative circle.