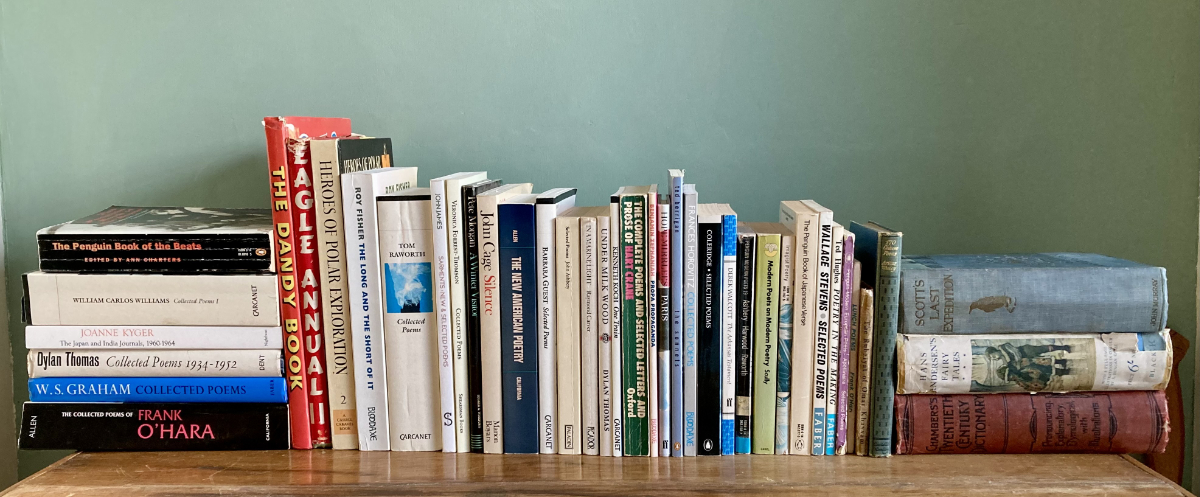

Cliff Yates gives us a tour of his poetry bookshelf and talks about Dylan Thomas, William Carlos Williams and Frank O’Hara

I read anything I could get my hands on when I was growing up, mostly fiction but also Chambers’s Twentieth Century Dictionary, the ambitiously titled Enquire Within Upon Everything, old Eagle Annuals and comics like the Dandy and Beano. I read the Oates biography, A Very Gallant Gentleman, from the glass-fronted bookcase in our front room and, along with a Christmas present Heroes of Polar Exploration, this was no doubt behind the Emergency Rations poems in Frank Freeman’s Dancing School where I sample texts from imaginary journals. Apart from Richmal Crompton’s Just William books which I loved, I had to wait for children of my own to catch up on many of the so-called children’s classics, though I did read Wind in the Willows in my teens when checking out the title of Pink Floyd’s first album Piper at the Gates of Dawn.

My main memories of school are of being bored, disaffected and disruptive. Mr Jones the PE teacher wrote on my report: “Thinks he’s the clown of the class”, and I was caned, slippered and slapped on a regular basis. I managed to enjoy English for the class novel (King Solomon’s Mines and Moonraker stand out). Poetry was thin on the ground but one memory makes up for it: the day Mr Young wrote the opening of Under Milk Wood on the blackboard (it must have taken him ages) and played us Richard Burton reading it on the school record player. I couldn’t believe language could do that. It stayed with me so much that on the day I left school for the printing factory I went into town and bought Dylan Thomas’s Collected Poems from W.H. Smith on Vicar Street before catching up with my friends in the Co-op cafe. It felt like a statement of intent though I had no idea what the intention was, and it wasn’t until years later that I started writing. I didn’t really know how to read the poems so I would listen to them in my head, not too worried about the meaning and seeing where they’d take me. I’d like to say that ‘Fern Hill’ stood out and it probably did: the glory of childhood and its passing:

Oh as I was young and easy in the mercy of his means,

Time held me green and dying

Though I sang in my chains like the sea.

And a few years later, studying English and American Studies at Swansea University, I found myself living in Sketty, not far from from Cwmdonkin Drive, Dylan Thomas’s childhood home.

… on the day I left school for the printing factory I went into town and bought Dylan Thomas’s Collected Poems

Another poetry book from that time was Edward Fitzgerald’s translation of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam, which Roy the poet gave me. I had a lot of respect for Roy, who turned up one day, sitting in a corner in the Coventry Cafe where we were hanging around, writing with a pencil in his notebook. I liked the feel of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam, the book as a physical object as much as anything, and learnt by heart:

The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

Moves on: nor all thy Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it.

I carried The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam around in my pocket for a while. In fact, I’ve just taken it off the shelf and found a card in it from the Kabul student hotel in Amsterdam where I stayed while hitchhiking around Europe, so I must have taken it on that trip too, which was at least three years later. Another lifetime, when you’re that age.

My degree at Swansea included a module in American Poetry and a poet that stood out for me was Hart Crane for the sheer beauty of lines like this from ‘Voyages’:

But now

Draw in your head, alone and too tall here.

Your eyes already in the slant of drifting foam;

Your breath sealed by the ghosts I do not know:

Draw in your head and sleep the long way home.

I started to write when we were living in Chester and I was working as an English teacher. I’d been getting students to write poems but hadn’t found a way in for myself (although I’d written bits and pieces over the years), and workshops were hard to find in the early 1980s. The change came in the shape of a Cheshire Poetry Project week in Anglesey with Pete Morgan and Gillian Clarke. I wrote a poem in Pete Morgan’s workshop, something clicked, and I was off. I was very taken with Pete Morgan’s poems, too. He’d just published A Winter Visitor about his time in Robin Hood’s Bay. There’s a warmth, humanity and conviction about his work, a way of elevating the ordinary, and his poems resonate like a ballad.

William Carlos Williams is a touchstone poet for me

William Carlos Williams is a touchstone poet for me, someone I go back to, to remind me what writing is all about. His two-volume Collected Poems is a monumental achievement, especially considering that he spent his entire working life as a doctor. I was drawn to ‘This is Just to Say’ (his note in the form of a poem apologising to his wife for eating plums) for its potential to impact on students’ understanding of poetry and its possibilities. Discussing the poem in a radio interview and answering the inevitable question about what makes that a poem, Williams said: “no one believes that poetry can exist in his own life … you can … make a poem about anything … the purpose of the artist … is to take the life which he sees and raise it … to an elevated position, where it has dignity”. In fact ‘This is Just to Say’ can be surprisingly provocative. On my first secondary school teaching practice, the teacher whose class I was about to teach asked me what I was going to do with his Year 10 and I showed him ‘This is Just to Say. “If a kid in my class wrote that,” he said, “I’d give it four out of ten”. Read ‘This is Just to Say’ on the Poetry Foundation.

I first came across Frank O’Hara in the 1980s, shortly after I started writing. I would travel across the Pennines to poetry readings and to Poetry Business Writing Days in Huddersfield, and a poet that I kept hearing about was Frank O’Hara so I tracked down a copy of his Lunch Poems and got hooked. There’s something about his poems, their apparent artlessness and lightness of touch, that somehow makes things seem possible. Take ‘The Day Lady Died’, which is essentially an account of what he was doing on the day that Billie Holiday died, ending with an account of the last time he saw her sing:

and I am sweating a lot by now and thinking of

leaning on the john door in the 5 SPOT

while she whispered a song along the keyboard

to Mal Waldron and everyone and I stopped breathing

This is pure O’Hara: minimal punctuation, unconventional line breaks, the impression of casualness, as if he’s written it down as it occurred to him, not explaining but trusting the reader. Read ‘The Day Lady Died’ on the Poetry Foundation.

I’m a fan of poetry that pushes the boundaries of what is possible, and Tom Raworth spent his entire life doing that. There’s an uncompromising integrity about his work, a willingness to take risks, and a sense that anything can happen, in the spirit of two key quotations from his poems: “the shortest distance between two places is to be everywhere” (from ‘Tracking’) and “the order is all things happening now” (from ‘Going to the Zoo’). And if there was a prize for best title, Raworth would surely have been in the running, though he’d have been the last person to bother to enter. Here are a handful of his titles, mostly from his collection Act, that I happen to have on my desk: ‘Future Models May Have Infra-red Sensors’; ‘7/8 of the Real’; ‘A Fall in French Furniture’; ‘Star Rats’; ‘Surgical Names: Ted’; ‘No + On = Noon (except when reflected)’; ‘Just Another Whistle Stop’; ‘How to Patronise a Poem’; ’Bounce.’

I’m a fan of poetry that pushes the boundaries of what is possible

I’ve been reading translations of Chinese and Japanese poetry since the 1970s when I became aware of its impact (and that of Zen) on the Beat generation, particularly Jack Kerouac and Gary Snyder, but it was only relatively recently that I came across Joanne Kyger’s The Japan and India Journal, 1960-1964, which chronicles her travels with Snyder in Japan (where they studied Zen Bhuddism) and India. The journal became an integral part of Kyger’s aesthetic and writing practice and this book shows her exploring its possibilities, in prose and poetry. Despite her seriousness of intention (“I want to write the world upside down”), Kyger never takes herself too seriously and can be deliciously ironic.

I’ve always felt an affinity with the work of Roy Fisher since I came across his Poems 1955-1987 in a bookshop, in part because of the Birmingham connection. I was only ten when we moved from Birmingham to Kidderminster but I still recognise the place in his poems. There is also a distinctive quality, a way of seeing, as if coming at things sideways, that catches me off guard however many times I read the poems. The work is so rich and various that there’s a lifetime of reading in Fisher’s The Long and the Short of It. One quotation won’t really do the work justice because of its extraordinary variety, but that’s not going to stop me, so here, to finish, is the last section of his poem ’Of the Empirical Self and for Me:’

What kind of a world? Even

love’s not often a poem. The night

has to move quickly. Sudden rain.

Thunder bursts across the mountain;

the village goes dark with blown fuses,

and lightning-strokes repeatedly

bang out their own reality prints

of the same white houses

staring an instant out of the dark.

Listen to Roy Fisher read ‘Of the Empirical Self and for Me’ on Poets Speak.