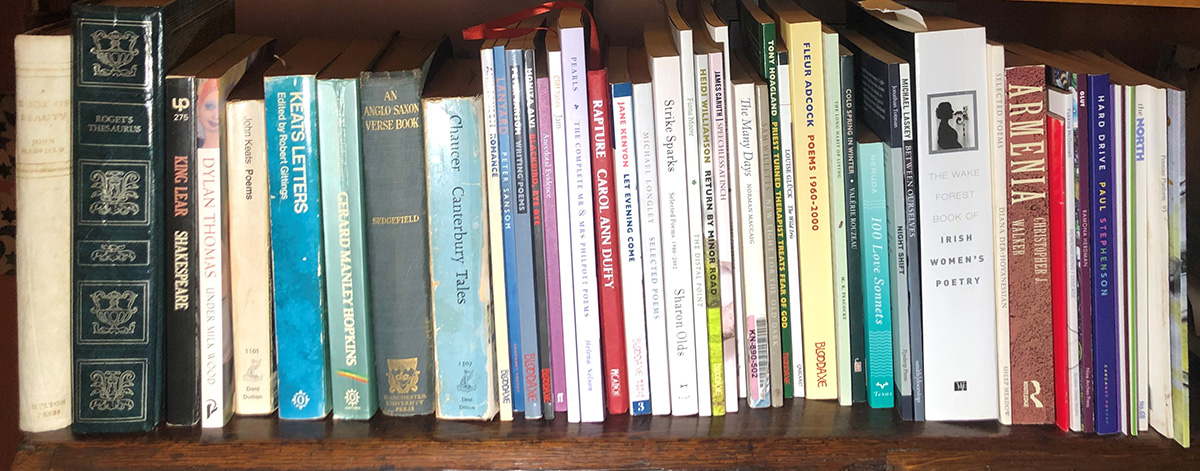

Sarah Mnatzaganian gives us a tour of her poetry bookshelf, explains her love of Shakespeare, Keats and Hopkins, and tells us how Ann and Peter Sansom helped her reconnect with poetry

For someone who took many years to become a poet, collating this bookshelf has been a fascinating experience. I’ve chosen a selection of the books which have led me through the forest of self-discovery to the place I now call home.

One of the first phrases which drew me like a moth to a candle was a quote from Walter Pater which I stumbled across in an anthology called The Book of Beauty by John Hadfield. The book was a gift to my aunt from an admirer in the 1950s and is full of romantic poetry and some beautiful prints. Here’s the quote from Walter Pater that captivated my ten year old self: “To burn always with this hard, gemlike flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life.” I’ve carried this phrase through my life, not realising that it sums up the fact that, to write poetry, you need to be almost painfully alive to everything around you.

I’ve always been a word addict, so to be given a grand green and gold edition of Roget’s Thesaurus when I started secondary school was a heady moment. I spent hundreds of hours in those pre-digital days, leafing patiently towards the right entry and discovering ridiculously obfuscating ways to say something simple. In those days, I’d much rather use three frilly synonyms to make my point rather than one plain and far more effective substitute. When I spent time in Jerusalem with my Uncle Hagop, who was an English teacher, I realized it was a family trait – he would never fail to find an opportunity to flourish his magnificent English vocabulary at the world. Why use one word when you can use three or four?

When I was fifteen, our state school head of English took a group of us to Stratford upon Avon. We camped. It rained. I tasted my first tzatziki at a Greek café and was chatted up by the waiters. My souvenir of that week was a small hardback edition of Shakespeare’s Sonnets which I read closely for many years (but have since sadly lost). Shakespeare’s genius with sonnet form and iambic pentameter entered my blood and has never left me (although I can count the number of my own successful sonnet attempts on two fingers). I also spent hours listening to recordings of the Tragedies loaned by a family friend, with Ian McKellen in the leading roles. I’d lie on the floor, reading the play, listening to his dry, searing voice and sobbing delightedly. How my bedroom carpet escaped mould I’ll never know. I was equally enamoured of Eliot’s The Waste Land and cultivated a cavernous voice to recite: “We are the hollow men, we are the stuffed men, leaning together, heads full of straw. Alas! …”. Deliciously depressing for a teen.

Another momentous experience was hearing Richard Burton reading Dylan Thomas’s Under Milkwood: “… down to the sloeblack, slow, black, crowblack, fishingboat-bobbing sea.” Perhaps I never experimented with psychedelic drugs because I knew where to get my fix – through language like this.

Keats stole my heart at 16, perhaps because he derived his linguistic energy from Shakespeare. I also read his letters fanatically, finding another tenet to live by: “The only means of strengthening one’s intellect is to make up one’s mind about nothing – to let the mind be a thoroughfare for all thoughts.” I found and underscored what I thought were the most compelling expressions of his love for Fanny Brawne, and copied extracts (no credit given to Keats) into letters to my boyfriend when I ran out of things to say. He was furious when he found out, but I hope Fanny would have found it funny.

Shakespeare’s genius with sonnet form and iambic pentameter entered my blood and has never left me

A more lasting influence has been Gerard Manley Hopkins, whose ‘Terrible Sonnets’ I memorised, and whose diaries I worshipped. I learned from these diaries the seriousness of being a poet: how closely he observed the natural world, and the massive challenge of creating an honest description with words, as accurate as a botanical drawing but imbued with the character of the artist, such as van Gogh’s irises or cherry blossom. Here’s Hopkins on bluebells: “If you draw your fingers through them they are lodged and struggle with a shock of wet heads; the long stalks rub and click and flatten to a fan on one another like your fingers themselves would when you passed the palms hard across one another, making a brittle rub and jostle like the noise of a hurdle strained by leaning against; then there is the faint honey smell and in the mouth the sweet gum when you bite them” (from his journal entry on 9 May 1871).

I’ve included Anglo Saxon verse and Chaucer on my shelf because, as a university student I spent many months trying to ‘learn’ Anglo Saxon and certainly took into my soul the rhythms and the character of its vocabulary, so different from Latin. Chaucer is earthy and playful, and the vagaries of Middle English are very liberating for a post-Johnson user of English. I still turn to the opening of The Canterbury Tales each spring: “Whan that Aprille, with his swete shoures sote, the droghte of March had perced to the rote …” if only to remind myself how different a music English made back then, and to remember that we can be free with our use of language now.

Motherhood and the associated brain fog and absence of time to read pulled in my literary horns until a poetry competition for parents at our daughter’s school inspired me to write about our post hibernation tortoise. I felt like a chicken full of unlaid eggs; poem after poem followed, virtually unbidden and with minimal clucking. A foolish submission to the Ledbury poetry competition and the predicable, echoing silence which followed, left me unable to write for several years, but thanks to the recommendation of a writer friend, I was rescued by an Arvon course with Ann and Peter Sansom. They are the most powerful poetry wizards I know. When Ann says, “Trust what comes” you tend to do just that, with great gratitude. As it was a beginner’s course, Peter would extemporize on the theme we were about to free write. I can see him now, sending effortless phrases into space, without fear of what would happen next. Like a good tennis player, his words always land lightly, just inside the line. Ann Sansom is a magnificent poet. I’ve never forgotten this powerfully unadorned last stanza from ‘Her Women (1463-1489)’:

One wipes the hefty wooden secateurs

one drags a sodden mop, two bundle sheets

and rags, one tends the stove. One leaves

and comes back, with the priest.

Cliff Yates was the guest reader on the Sansom Arvon course: what a perfect choice. Riding up on his bike from Craven Arms, he strode into the evening gathering and rolled his glorious, grounded, funny, unique poems towards us.

I learned from the diaries of Gerard Manley Hopkins the seriousness of being a poet: how closely he observed the natural world, and the massive challenge of creating an honest description with words, as accurate as a botanical drawing but imbued with the character of the artist

I’ve been very lucky to get to know Wendy Cope since she and her husband moved to Ely. We’re good friends now so we discuss many things besides poetry, but when she gave me feedback in the early years she would sometimes ask: “Do you really mean it, Sarah? Is it true?” Or, “I don’t understand this line and that annoys me”. Fantastic training from a mistress of clarity. She is serious and funny and scary all in one go, so I particularly love her pastiche poems in Making Cocoa for Kingsley Amis which never fail to make me laugh:

Because time will not run backwards

Because time

Because time will not run

Hickory dickory

(from ‘A Nursery Rhyme’).

The downside of reading English at an old fashioned university is that poetry pretty much ends with Eliot, so it was and still is a revelation to catch up on contemporary poetry, often thanks to the choice of prompt-poems at poetry workshops and anthologies such as Anthony Wilson’s Lifesaving Poems and the Bloodaxe Staying Alive series, as well as a writer friend’s early gift of Carol Ann Duffy’s Rapture which I still find stunning in its clear, passionate but grounded imagery:

I tend the mobile now

like an injured bird.

(from ‘Text’).

My bookshelf isn’t wide enough to show all the discoveries of the last seven years, but I’m a happy convert to the work of Sharon Olds and Mary Oliver; very different poets, both of whom tempt me towards a more confessional style of writing. Old’s Stag’s Leap left me reeling: could I ever commit such personal material to poems intended for the eyes of strangers? I adore the charm and energy of Tony Hoagland whose confessions are more nuanced and ironic than Olds. Here he is in beguiling form in the opening of ‘Butter’:

I think it was Marie who first taught me the art of spreading flattery on people

then smearing it around like marmalade on slabs of whole wheat bread.

(in Priest Turned Therapist Treats Fear of God).

Norman McCaig is another poet who often makes me smile. I was amazed to find none of his work at the Arvon library at the Hurst but perhaps it had walked off in a poet’s pocket. McCaig, a prolific Scottish poet, has a piercing but kindly eye and I enjoy the musicality and humour in many of his poems such as ‘Toad’ or ‘Summer Farm’:

A hen stares at nothing with one eye/

then picks it up.

(from ‘Summer Farm’).

As often happens, this master of comedy plays the other card equally well, as in his unforgettable elegy for his wife,

She grieves for my grief. Dying, she tells me

that bird dives from the sun, that fish

leaps into it. No crocus is carved more gently

than the way her dying

shapes my mind.

(from ‘Memorial’).

Another original delight is M.R. Peacocke, one of the many fine poets published by Helena Nelson of HappenStance Press who has also been a generous mentor. Here’s an extract from an extraordinary poem called ‘Put’:

At last my door, and putting everything down

to fumble for the key before life to come

and becoming aware of Put: these bags, weight

of potatoes, a couple of jars, all the stuff

settling into a sideways loll.

Last year I was thrilled to receive from an Irish bow maker friend, in return for the tiny pamphlet I’d sent him, a huge anthology of Irish women’s poetry which includes generous selections of the work of 16 poets, including Eavan Boland whose work I have long found inspiring, along with others whose names I hadn’t yet come across such as Eiléan ní Chuilleanáin and Kerry Hardie. Hardie’s poem about the death of her father is magnificent:

The sky didn’t fall.

It stayed up there,

luminous, tattered with crows,

all through

January’s short days,

February’s short days.

(from ‘After my Father Died’).

The last few years have seen me writing about family and learning more about Armenian history, including painful study of the Genocide of 1915-23. I’ve also discovered contemporary poets such as the magnificent poet and academic Diana der Hovanessian whose work has heart, depth and discipline, and who also translated the work of a wide range of classical and contemporary Armenian writers.

I was rescued by an Arvon course with Ann and Peter Sansom. They are the most powerful poetry wizards I know

I’m lucky to have been published by Against the Grain Press, and I have a few of their recent publications on my shelf.

I wouldn’t be the person – or poet – I am without the friendship and support of many fellow writers, especially an online Saturday workshop group formed at the start of Covid: Ramona Herdman, Kathy Pimlott, Pam Thompson, Fokkina McDonnell and Paul Stephenson, whose first collection, Hard Drive is a virtuosic exploration of loss. Towards the end of my shelf are copies of a few journals and magazines: a tiny taste of the selfless work of editors who select and collate the work of living poets online and in book form, to whom I’m forever grateful.