Helena Nelson and Hilary Menos discuss the recent Best Forward Prize-winning collection With My Back to the World by Victoria Chang (Corsair, 2024)

[…] But I learned that it’s

possible for a sentence to have no words. That the meaning of

a word can exist without the word. That life can still occur

without a mind. That emptiness still swarms without the

world. That it can be disconnected from the wall and still

light up.

[‘With My Back to the World, 1997’, p. 3]

Nelson: This definitely does it for Alycia Pirmohamed, one of the Forward Prize judges, who warmly praised it before Victoria Chang’s reading at the Forward Prizes event. What do you think? Can emptiness be disconnected from the wall and still light up? What did you think of this opening poem in the book?

Menos: At first reading, I didn’t understand what Chang meant by the being disconnected bit, and I felt crotchety and inclined to pick at the individual phrases and lines, and take issue with them. For example, surely it is NOT possible for a sentence to have no words? The very definition of a sentence is “a set of words that is complete in itself” (unless she’s talking about punishment, but this doesn’t seem likely). But your example – that emptiness can be “disconnected from the wall and still / light up” – is actually not the most problematic bit, for me. I think it evokes the notion of emptiness (or depression – a lot of this book is about Chang’s depression) as something (in this case a kind of appliance) which is usually connected to something other than itself / gains power from something external, in order to act / perform / generally do its thing. It seems to me that Chang is saying her depression continues even when she turns her back on / disconnects from the world. In that metaphorical way then yes, I guess ‘emptiness’ can be disconnected from the ‘wall’ and still ‘light up’, or at least it is true to say that Victoria Chang perceives that hers does. She’s saying that her depression is intrinsic to her, and not created by or powered by the external world.

I have more of a problem with “The best thing about emptiness is if you close your / eyes in a field, you’ll open your eyes in a field”. What do you get from that?

Nelson: Oh dear. What I want not to do is hurl criticisms at a prize-winning collection as if to bring it down a peg or two. Somebody always does that, and I really do believe that poetry, if it has any soul at all, has nothing to do with competition. These poems are not to blame for winning the Forward Prize. They just aim to be whatever they are and do whatever they do. I think poetry is, at the very least, a communication. A communication needs a response. In Victoria Chang terms, that might be said like this:

“What we make can only be seen by someone else.” [‘Falling Blue,1963’]

I see that this poet’s ‘gnomic statements’, as I call them, make you want to argue. I feel the same about many of them, and it’s a feature of her style that they recur. On the other hand, I did like this opening poem, which was the first I read. I liked its oddness, and I found its structure accessible and easy to read. It has a ragged right-hand margin: it’s not fully-justified into a box like so much that comes later. The phrasal repetitions give it a melodic surge. I especially liked:

[…] The first person ran

away like a horse. When the first person left, there was no

second or third person as I had originally thought. All that

remained was repetition. And blue things.

This conveyed a sense of isolation and unhappiness I could relate to. Odd but not impenetrably weird. I liked the simple diction. I liked the irregular groups of lines. I was content to let the idea of a sentence without words float out there (whatever it might mean and in whatever sense it might, or might not, be true). The possible ambiguity of the word “sentence” didn’t occur to me. The idea of emptiness “swarming” interested me, since it’s obviously contradictory. I thought the bit about being disconnected from the wall was something to do with canvases in the art gallery (see Agnes Martin discussion below), and I visualised lit-up paintings. I didn’t object to the “field”, partly because it tied in with the horse that ran away, so the field was obviously empty. But a field’s a good quiet place to be, a safe and natural place, though I might prefer a meadow. I’m not saying I found the poem deeply satisfying. But I liked it as an introduction to the book. I did want to read on.

We’ve both done an exercise in writing in the style of Chang. It made us look out for characteristic features and stylistic repetitions. I think we should share what we came up with, not only because it’s also a form of detailed response, but also because for me, both are remarkably convincing. Not that they sound exactly like Victoria Chang, but they sound perfectly credible as poems. Pastiche but not piss-take. Did you find this useful? Did you learn anything from it? Here’s mine:

The Beach, 1964 [p. 86] is a black square. At first it appears solidly black. Then I see it is less solid in the bottom right hand corner. I imagine it is a photograph of a beach at night, in which I can, with difficulty, make out several flanks of undulating sand. The more I look, the more sand I see. The sea in the distance is black and invisible. If I put my ear to the page, I hear waves lapping the shore. If I hold the page up to the light, even the black sea is permeated with stars. This page has no number. I’m very careful not to have ideas, says Agnes, because they’re inaccurate. There are two inaccuracies in the sea, one is astonishment, two is foam. To be astonished by a poem is to love it. The waves in the sand are the rhythm and the landscape of foam. The lines of the poem are not true lines. They are words of varying sizes placed on the page as though a line were there, but no grid is visible. All lines know that the human soul sees horizontally. I lift my eyes to the groups of words on the opposite page and they appear to me as lines. I bring my meaning to them. To bring meaning has meaning, even as words dissolve. I have learned that meaning is beyond words just as our souls are beyond our minds. That we can tear a book into a thousand small pieces without realizing that we have disintegrated a whole beach and maybe other landscapes too.

Menos: Ah, I really like what you did there, even down to the American spelling of ‘realize’. Yes, I found writing in the style of this book was easy. Chang uses a lot of non-sequiturs. She makes statements that don’t really make sense but look as if they might because of neighbouring sentences. There are deliberate repetitions (e.g. “Agnes must have miscalculated. There are 127 lines […] I miscalculated my depression.”) She often ends with something really odd or obscure. For me, this last sentence in the opening poem (“The best thing about emptiness…”) is one of the odder ones. Overall, I guess the first piece is about the process of focusing on one’s own internal landscape (field?) rather than the external world. Agnes Martin did this in order to better control her schizophrenia. Presumably Chang is mimicking this turning away from the world in order to better explore / control / mitigate her depression. My impression is she wrote this opening piece specifically as an introductory text. It references themes and tropes that run throughout (depression, language, horses, emptiness, blue), and of course it justifies the collection’s title. Here’s mine:

Night Sea (1963)

There are 2852 tiny coffins jostling in this blue ocean, each small rectangle filled with sadness. Do they each contain their own, individual, singular sadnesses or is the sadness one large unified sadness divided between them. And is it divided equally? Are some of the coffins nearly empty, and some bursting at the seams? The dead people who were in the coffins have fallen out and are congregating on the ocean bed. Agnes said you just can’t be an artist if you can’t be alone. Each coffin is alone in a different way, and all coffins are lonely. The one I’m standing on holds my depression. Once I walked into the sea until I felt the waves lapping my chin and all I could think about was the roses in the vase on my table, and how blue they were. The roses were blue, and that meant something. This is the problem with meaning. Perhaps it’s not the colour of the roses we are trying to see but the colour of our own souls. I took the ocean away and tried to write what was left. 2852 coffins, laid end to end. All of them empty.

Nelson: Very naughty! All those dead people falling out of their coffins! And yet, as you went on over-egging the pudding, I began to find it curiously moving. ‘Each coffin is alone in a different way, and all coffins are lonely.” I knew precisely what you were doing there: manipulating my emotional response with loaded words (coffins/lonely) and yet I still felt absurdly moved. When you said “I took the ocean away and tried to write what was left”, I actually empathised. Admittedly, I was perturbed to find I could be manipulated so easily. But like me, you brought in a comment from Agnes Martin (and the whole book is, according to Chang, “a conversation” with that painter) and it illustrates beautifully how the quotations call in a more friendly, conversational tone. What we can’t imitate, obviously, is the gallery experience, the stimulus for Chang’s poems. Do you need to know something about the painter to approach these ekphrastic poems meaningfully? I dived straight in without realising the strange titles are all paintings (no, it’s not plagiarism to steal other people’s titles) and was puzzled why some were dated before the author was born. Later the penny dropped that most poems here connect to a specific artwork, which (thanks to the internet) I could often (but not always) find online. Did that help with understanding the poems, do you think?

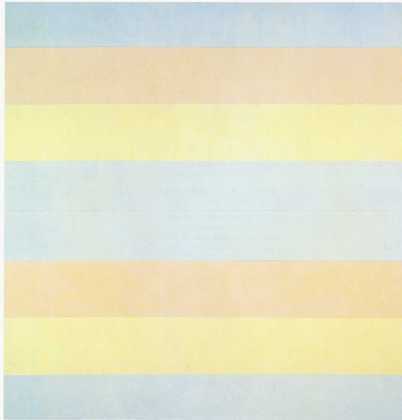

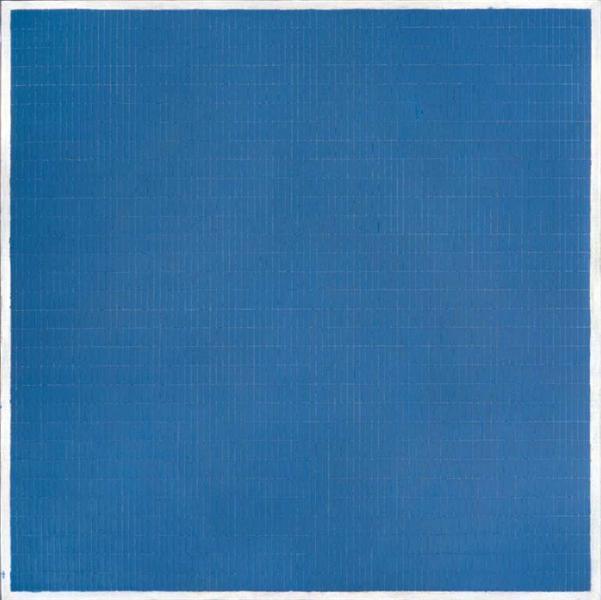

Menos: I think it is useful to know that ‘On a Clear Day, 1973’ (the second poem) was commissioned by the Manhattan-based Museum of Modern Art as a response to a particular artwork – see the Agnes Martin picture and Chang’s poem here and hear Chang read it, below.

This was Chang’s pathway into the book. In the conversation with her on the Forward site, she says:

“When I read the poem aloud for the first time, I suddenly realized that I wanted to keep corresponding with Martin and her work. Because of the challenges I was facing in my life related to my father dying, as well as some mental health issues I was dealing with, suddenly Martin’s work had a profound poignancy that it hadn’t before. I think working within the tradition of the ekphrastic was both exhilarating and challenging. I think the poem that began my conversation with Martin’s artwork is most important to me because it was the spark that began that conversation.“

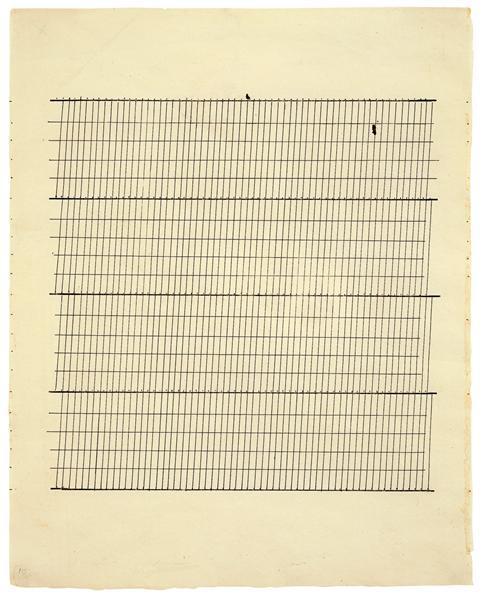

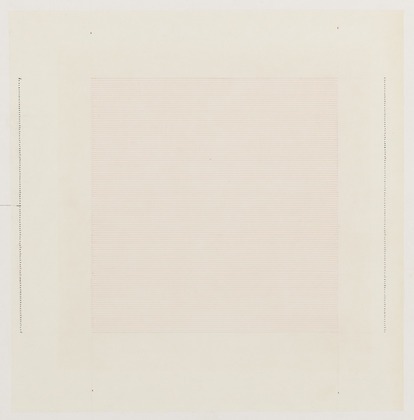

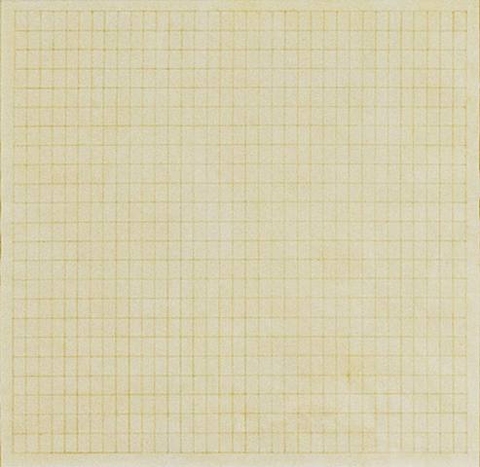

I think it’s also useful to know that the painter, Agnes Martin, struggled with her mental health. Her decision to leave New York and live alone in the desert to be able to focus only on painting was at least in part to keep her schizophrenia under control. She literally turned away from the world. Beyond that, I’m not sure how much you need to know about Martin in order to read Chang’s book meaningfully. I see the connections between certain specific paintings and Chang’s responses – some of them are obvious. Chang often describes the painting in her poem, for example, counts the number of grid squares, references the thickness of the pencil lines, etc. But it’s a one-way street. In looking up the background to the painter, I learned a lot about Agnes Martin (I found her work powerful, and the details of her life absorbing) but that didn’t illuminate the poetry particularly. And the content of the poems (mainly about Chang) didn’t help me understand Martin’s paintings. So in that sense the book doesn’t really strike me as a “conversation” between them.

Nelson: Do you think it’s inappropriate of me to feel the book is too much about Victoria Chang and not enough about me (the reader)? Too personal? Or is it just that I don’t want her depression as my companion?

Menos: I’m not especially drawn in by Victoria Chang’s depression. For me, she hasn’t made something beautiful (in the way Agnes Martin has) out of her experience. She doesn’t speak to me. I’m probably too cheerful / churlish / literal / short tempered to appreciate her.

Nelson: But now you’re doing that thing we all tend to do, blaming your lack of response on yourself, rather than identifying a lack in the work. The fact is, it doesn’t ‘speak’ to either of us strongly, it would seem, or at least only in part, whereas it evidently did communicate powerfully to the Forward Judges. So what’s going on? I don’t think we can ascribe too much to the fact that it’s ‘about’, in some sense, depression. It doesn’t really matter what poetry is about, does it? In the end, it’s the way it’s handled that does or doesn’t appeal. And we can certainly admire skilful writing, whether or not the subject matter is particularly relevant to us.

Menos: Well, I do sometimes worry that I am just too literal to enjoy this sort of poetry. Aside from being a bit of a grammar fascist and a staunch defender of established systems of punctuation, I also really feel the need for statements in a piece of writing to make sense, or at least not to make NO sense. When Chang says “There / must be a reason why we look at the mirror and see ourselves, not someone else. Why we see a face, not words.” I can’t help responding “That would be because it’s YOU looking into the mirror, not someone else. And (ffs) it’s a MIRROR.” Am I too literal, or is she too gnomic?

Nelson: She’s too gnomic for me. I think that might be what alienated most, actually. I mistrust assertions that sound ‘poetic’. Whenever she wrote something like, “The sayable, by nature, is an / elegy.” [‘Untitled IX, 1982, p. 31], I found myself scribbling in the margin (in pencil) “No it’s not!!”

She’s too gnomic for me. I think that might be what alienated most, actually. I mistrust assertions that sound ‘poetic’.

Menos: She definitely uses language in a slippery way and sometimes I find that difficult. I used to think everyone felt the same way about this, but Andy doesn’t give a monkey’s about the literal sense of words (or grammar, or punctuation — it’s taken me twenty years to cut his ellipses down to three, they used to run on into the tens or, worse, stop at two). But he still feels that a poem has to take him somewhere, or be beautiful to read / hear. I understand that poetry often uses language in a non-literal way, and can require a leap of faith, but with Chang this happens a lot, in a way that rarely convinces me.

What I do like is her sense of humour. She can be quite sharp. For example, in ‘Untitled, 1960’ [p.70], she writes: “When people die, the eyes still want to remain open, to continue stockpiling images. Funeral homes use spiky eye cups to keep the eyes shut.” I’m interested in the mind that generates that juxtaposition.

Nelson: You found that funny?!

Menos: I find the juxtaposition with the previous line (which sounds rather over-serious) comedic. It evokes an image of funeral home workers grappling with spiky eye cups to press and keep the eyes of the dead closed. It’s macabre, absurd, and strangely comical. Maybe it’s just me. In ‘Happy Holiday, 1999’ she says: “The horizontal line is gentle. The vertical is aggressive. // Surveillance is vertical. War is vertical. A holiday is horizontal. / Unless it’s a war holiday, then it’s a square.” I’m amused by the notion of a ‘war holiday’. She takes me with her, in this piece, and I’m completely (and strangely) happy to accept her assertion at the end of the poem that her heart has become a rectangle which makes the sound of splashing. In ‘Happiness [from Innocent Love Series, 1999’, p. 79] she says: “Agnes liked the horizontal line better than other lines. I like it too // because its weight is distributed so that more depression can hang from / it like laundry.” The line finishes in an unexpected way, but totally makes sense to me.

Nelson: Well, it’s interesting that you chose these two poems to comment on. I don’t find either of them amusing, but I like several things about them. Particularly that their shapes have a relationship to their ideas. The first of the two, ‘Happy Holiday, 1999’ is cast in right-justified couplets, effectively a series of stripes – and she’s responding to a series of red bands in the painting. And she’s focussing on the horizontal. Also the idea that different shapes have emotional resonance interests me. And if you accept that this is possible (as it is certainly for both Agnes Martin and Chang herself), the idea of splashing starts to be tenable. I don’t think it’s gnomic. I think it’s surreal. Martin is not a surrealist but Chang often is. The other poem you just mentioned, ‘Happiness (from Innocent Love Series, 1999)’, is two blocks of five lines – horizontal rectangles – with a thin block in the middle (a sandwich filling). This one is overtly about depression but actually it did make me smile, although I wasn’t sure that was the intention. She says the reason she, like Agnes Martin, likes a horizontal line best, is “because its weight is distributed so that more depression can hang from / it like laundry”. That’s both ridiculous and surreal, isn’t it? But after that, I thought she went off the deep end with: “The only way to see if my words are poems is if I crush / them into lines. I do this so no one can see my insides. I’ve learned that / the words are only poems if, when flattened into a line, the meaning is / still there.” The washing line has disappeared and a crushed line of words has taken over.

Menos: Something else I like is the way she personifies unusual things – her solitude in ‘Grass, 1967’, for example, where she says: “Sometimes / my solitude grabs my phone and takes a selfie, posts it / somewhere for others to see and like. Sometimes people / comment on how beautiful my solitude is and sometimes / my solitude replies with a heart.” I get this – it carries a sense of disassociation or disconnection.

Nelson: Really? I find that solitude posting a heart … well … it just goes too far!

Menos: There are other things I like less. ‘Leaves, 1966’ [p. 39] ends: “Language isn’t actually inside us, as I had thought. We / are tenants of language. We are leaving while writing.” This makes my head hurt; too many abstract concepts which just don’t seem to fit together in a meaningful way. So some parts of Chang’s poetry absolutely work for me, while others leave me cold or confused.

Some parts of Chang’s poetry absolutely work for me, while others leave me cold or confused

Nelson: Ah yes, And ‘Leaves, 1966’ has ants in it. Those ants appear regularly, don’t they? They reminded me of Pascale Petit’s ‘Self-Portrait with Fire Ants’, which I guess Chang wouldn’t have read anyway. But they’re a recurrent surreal feature. In this poem, they’re clearly leaf-cutter ants. But the imagery is deliberately muddled, I think. The ants are cutting up her depression “to feed a queen”, so there the depression is like a leaf. But then she says “everything / resembles // leaves at some point, the way they need a host”, and I start to think (we’re both too literal-minded) about the way a tree is not (biologically speaking) a “host”. The leaves are actually part of the tree, though you might argue the tree is a host to the ants. And then suddenly she blows my mind, though maybe not in a way I enjoy: “Language isn’t actually inside us as I had thought We / are tenants of language. We are leaving while writing.”. Being a tenant of language, just as an ant might be a tenant of a tree (in a sense) is possible, but then “We are leaving while writing” – that’s not so much wordplay as punning on the word “leaf”, and it’s fearfully complicated. And what I have I learned? I’m shaking my head again.

But those ants, those ants. They’re not just in the Agnes Martin poems. They’re in the central sequence of the book, which is quite different. They’re depression ants. Let’s take a look at the central sequence, ‘Today’, which takes its overall title and subtitles from On Kawara’s series: Today. This sequence has a consistent form throughout: a set of ten-syllable lines. No metrical pattern, but definitely syllabics here. What did you make of it?

Menos: I first read this section as simply a series of Chang’s diary entries dating from January 4th 2022. Then I read about ‘Today’. For those who don’t know, Japanese conceptual artist On Kawara began painting dates (calendar dates, not fruit) on January 4th 1966 (note the parallel with Chang’s first date) and continued for nearly five decades, painting one nearly every day, sometimes two or three, generating nearly 3000 paintings. Each ‘date painting’ is a monochromatic canvas of red, blue, or grey with the date on which it was made inscribed in white. It’s “word art”. According to the Guggenheim, the series “speaks to the idea that the calendar is a human construct, and that quantifications of time are shaped by cultural contexts and personal experiences.”

I can see why Chang was drawn to Kawara’s work. From 1962 to 1964 he made about 200 Paris-New York Drawings – their motifs include stripes and grids much like those of Agnes Martin. I guess Chang is emulating his ‘Today’ series in that she’s creating a brief record of each day. The ‘diary entries’ make a kind of long, thin poem, all in, as you say, ten syllable lines, and the collection also includes a reproduction of them in their original format – it is long and thin and makes me think they were originally written onto a mobile phone. Why ten syllables? What does that do?

Nelson: It think it imposes a form and a discipline. The first two entries are even in parallel metrically, although after that she’s back to prose rhythms. But the only meaningful connection I see between these poems and On Kawara is the series of dates. I’m not even sure it helps to know about On Kawara when you read this. Do you think it does?

Menos: On Kawara is preoccupied with chronological time and its function as a measure of human existence. Like you, I don’t see that this is particularly relevant to Chang’s second section, except in the broader sense of time ticking away, and no time left equals death. Also, ten syllables is a creative constraint, yes, but there’s no point in a constraint per se. And ten syllables alone isn’t much of a constraint – it’s hardly an abecedarian or a ghazal.

Nelson: Actually I find ‘Today’ depressing to read, not just because of the content (which is undeniably grim) but I think because of the flat tone. I can’t imagine reading these poems for pleasure and I didn’t find the artwork illustrations illuminating, though it’s interesting that some of them are blacked out (erasure, I guess, which is clearly something that interests her, but not so much me). I feel these poems record something vital for the poet (which I can respect), but not for me. I sound heartless, don’t I?

Menos: In an interview in The Rumpus, ‘Interrogating Grief: A Conversation with Victoria Chang’, Chang says: “I can be an obsessive writer. I’m very aware of the pacing in a book because of this personality characteristic. By the time I’m finally putting together a book, I’m aware of how my poems can be tedious, exhausting, require too much energy, or have too much sameness to them. These are things I’ve heard from other people about my personality, too.” Later, talking about her recent collection, Obit, she says: “I actually fall asleep all the time reading my own poems or doze off. I sometimes wonder if this means my poems are boring!” I guess she might be referring to what you call the flatness of tone in the central sequence. Here’s a flavour:

Jan.20.2022

Today is your birthday. Someone came in

and said, they’re still not feeding him?, thinking

I was someone else. The eyes press against

the glass of my brain. They can’t touch me but

they won’t stop looking. Eyeballs have footsteps

too. When they walk, they sound sticky. Hundreds

of them have gathered outside the window.

Nelson: Ah yes, there’s the surrealist at work again. Those walking eyeballs, which are starting to remind me of Selima Hill’s bizarre imaginative leaps.

Menos: Do you think you sound heartless? I’d say reasonable. Like you, I do feel these central pieces are more important for Chang than for me. If Chang (or her father) was a personal friend then it might be different. The inclusion of the illustrations showing what we might call “her workings” doesn’t really improve things – it’s just more paper to turn. As it is, I’m left hoping for more meaning (and less paper). On the other hand, what comes across to me most is Chang’s ambivalence towards her father, and I find that engaging. I think she conveys this really well. For example, she says:

[…] If I lean in

I can hear all the words said in your

life, now in a different order. There’s still

no love even though I’ve looked through all the

words twice. I go digging in the mass grave

of language for the extra loves and I

end up bringing loneliness back with me.

Later she says: “I let my father die alone […] I cried zero times. […] Another day went by. Still no feeling.” And later still, speaking as if she were her own father: “I saw myself for who I was—evil, / full of syllables. Poets are useless.” I’m not sure what the “full of syllables” bit is about but other than that, it feels very real to me. I can relate to it.

Nelson: I was interested in the way she couldn’t access an emotional response in herself, as in p. 51 above. That’s true to life. And I can admire her honesty in this horrible situation. But I don’t find the prosiness aesthetically pleasing. And I get irritable with the eyeballs on Jan 20, or with nit-picking details, like p. 46 where one of the titles (Jan.21.2022) is left sitting on its own at the bottom of the page with no content. Who would you recommend this sequence to? Who would like to read it? Someone who was sitting out a long death? An optimistic young person? Hm. Probably not.

Returning to the Agnes Martin poems, I’d like to know what you think of ‘Untitled #5, 1998’ [p. 91]. On the facing page of this one is a facsimile of the text (she has done this lots of times by now) and in this case there’s a thick swirly, graffiti-type line through every single couplet (the poem is structured in wide two-line stanzas). The opening statement is:

In the Cy Twombly room, I wanted so badly to be drawn on. The

curves of Twombly’s crayon as if possessed by syntax.

I think the swirly lines are in the style of Twombly. Effectively she is drawing on herself with “curves possessed by syntax”. I don’t feel this is subtle. Maybe it’s not intended to be. Then more gnomic statements, although this time in a perhaps/maybe mode. “Maybe every poem is an // attempt to describe lightning. Maybe lightning can’t be described / which is why there are so many poems.” And then “Some of us spend our lives trying / to pin language to the sky but language is the one that gets to stay.” Is that a metaphor? And in what sense might the sky metaphor be ‘true’? We (the living) certainly don’t get to stay. But I’m not sure the language we’ve been pinning to the sky gets to stay either. I’m not sure anything gets to stay. But most of all I was puzzled by the end of the poem:

Sometimes I think about the child that the grandfather dropped out

the window of the ship, and wonder what happened

to the scream that went down the side of the boat. And where all

the people who heard it went.

I couldn’t help visualising this, and found it haunting. But what grandfather? I was imagining a porthole, through which a child was deliberately dropped. But why would her grandfather do that? In any case, portholes don’t normally open. I googled the story. In July 2019, Chloe Wiegand, a toddler of 18 months, fell to her death on board a cruise ship docked in Puerto Rico. Apparently, her grandfather lifted her up to look through a glass wall inside the ship, later claiming he hadn’t realised the glass panel was open. The child fell through and died instantly on the pier over 100 feet below. Later there were contested versions of who was to blame. But none of the versions squares with what I had imagined. I thought, she had fallen “down the side of the boat” and into the sea (although the poet never mentioned the sea). I thought the grandfather had deliberately dropped her (the lines above give that impression). Did the child scream? (She might not have had time.) Most puzzling to me is why the poet has put this event into her poem. It’s accepted practice to write ekphrastically – a poem in response to a painting. This is a response to a news story, and to me it distorts what really happened. Is that what art does? Does it matter? (I feel awful for that grandfather.)

Menos: It’s one thing to write about a piece of art that someone has made for public viewing, perhaps another to write in response to a news story about real people. Of course Chang can write what she wants about anything, but this is perhaps in poor taste. Especially as, yes, it does apparently distort the true facts of the case. More importantly, it doesn’t seem to me to be doing anything useful here. What do you think?

Nelson: I think she half-remembered a news story that had stuck in her head. It connected for her and she popped it in. Perhaps she didn’t see any reason to look it up. But it wasn’t her own idea / image; it was a real event in other people’s lives.

Menos: Yes, I’m bemused by this. In fact, the more I read of this collection, the more polarised I feel. Some of it is frankly impenetrable, but other parts are impressive. I’m very taken with this piece about her father’s cremation, for example, where she writes:

Twice now I’ve read about the chamber,

this time I learn it is called a retort,

also a sharp reply. This time, I read

about the pugilistic stance when they

burn the body, the boxer-like pose the

body makes. I think about my father,

alone in the retort, in a small box,

two thousand degrees, his legs bent, his fists

ready to punch me and my live flesh.

Wow! I think this is splendid. The writing crackles with energy and force, and the imagery is arresting and powerful. So much is conveyed about the relationship between father and daughter. It’s smart, and it’s affecting.

Nelson: I am less impressed by this description than you. I feel unhappy about the blur between her father, her father’s body and her feelings about her father. She says earlier:

I wonder if it’s possible to live

by persistence, wanting so badly to

remain secured to the body, that his

soul left fourteen years before its vessel.

Soul. Another highly emotive word. Chang uses it in two of the Agnes Martin poems too, where her own soul seems to float in and out of her body unimpeded. I assume here she means her father’s illness had left him cognitively absent. And yet, when he does die, she continues to talk as though his body is him: “Today they burned my father.” (They burned his body.) “Today / my father is in a small jar.” (His ashes are in the jar.) Maybe this is a true reflection of the confusion we all feel in this situation. But it seems to me emotionally manipulative: “What is dying but a / form of hunger, visible to God?” What can I possibly do with a statement like that? Throw in God and your reader has no escape.

When I finally reached the end of the father sequence, I found the remaining Agnes poems surprisingly friendly. I was relieved to get back to openings like “Yesterday I slung my depression on my back and went / to the museum.” [‘Leaf in the Wind, 1963’, p. 82]. But there are a many more poems before the end of the book, and none are light reading. Usually I work my way through a collection for review at least twice, and after that I dip in and out several more times. Here, one slow immersion was enough. I was glad to get to the last poem, but I like it. ‘Friendship, 1963’ seems more joyous to me than the others. She’s writing about her favourite Agnes Martin canvas (you can get a sense of it here). (I imagine it might be stunningly bright in a gallery). The poet draws in the feeling of closeness she’s developed with Agnes Martin, so the title of the painting and the meaning of the poem connect. She shares experience that feels true (sometimes life itself is gnomic). She had called the front desk several times and the phone was answered each time by someone called “Angel”. That has to be true. “While I stared at the gold rectangles, two attendants / talked about whether to work overtime and get paid time and a / half.” Similarly, that detail must be real. Her sharing of experience felt generous to me, and rich. I’d like to see that painting. And although a pamphlet-sized set would have been enough for me, I won’t forget these poems. Not their oddness, nor their shapes, nor the way they made me work.