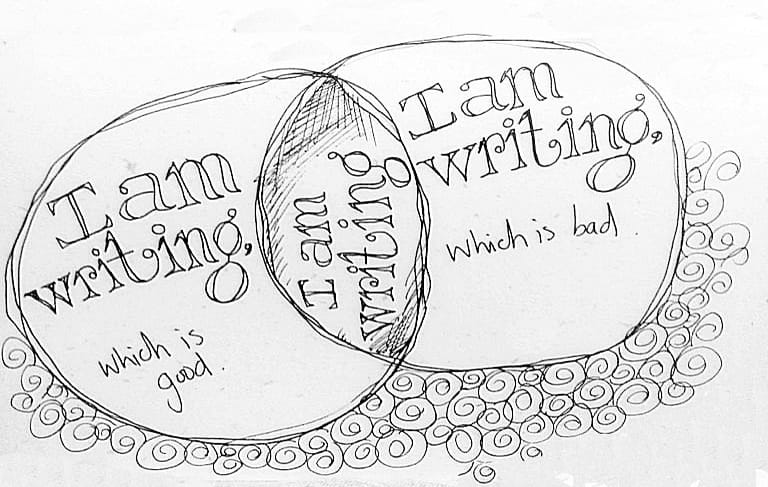

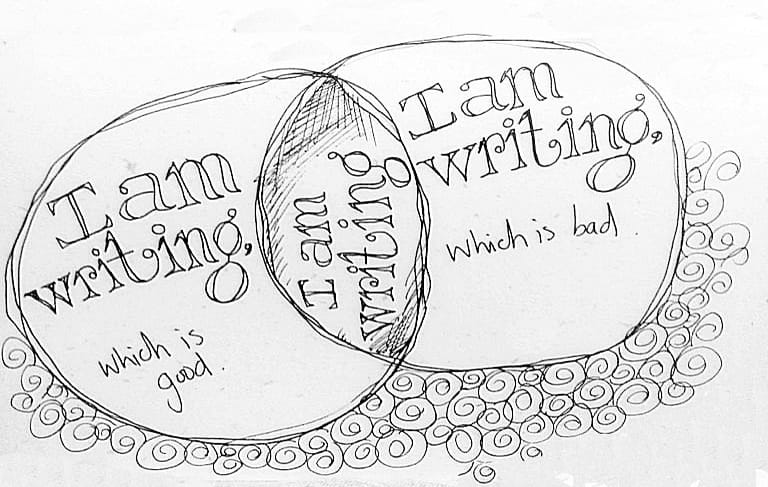

The Friday Poem would like to offer two versions of Jane Burn’s lyric essay A Poem Begins. In her original version Jane uses justified text and variable white spaces between letters and words. Partially-sighted readers and readers with dyslexia can find this problematic. We’ve written about accessibility here. We discussed this with Jane, who explained that her version was written specifically taking into account her own access needs. She says: “I have always had huge struggles with blocks of text. This has severely restricted my own ability to read / decipher text and on my ability to write, especially when it comes to essays. It was only when I began to learn to write in a style freed from large, solid blocks that I began to find expression. I must ‘break down’ what I am writing otherwise I utterly fail to express myself. I represent my roaming thought processes as they occur to me”.

We think it’s really interesting that the version Jane wrote to suit her own access needs is less accessible to some other readers, while the supposedly more accessible version is actually less accessible for Jane. We agreed with Jane to offer two versions of her essay. Version One, Jane’s original version, should suit readers who prefer not to read large blocks of text. Version Two should suit partially sighted readers or readers with dyslexia. Jane says, “I do understand the difficulty my original version might present to others. In changing my essay into a form that will hopefully help others while reading it, I felt as others might feel on reading my original – stressed, panicky, nauseous and shut out. Access needs differ between individuals and I hope, in offering two versions of the essay, we go some way to addressing these requirements and encourage further, valuable discussion of this subject.”

For Version One click here, and for Version Two click here. If you’re reading this on your mobile phone, for best results view it on landscape.

Lyric Essay – A Poem Begins, by Jane Burn

iA Poem Begins?

Poetry is a laser beam to the brain / a raw vein

leading straight to the heart. We find a poem

that affects us / that we love and we resonate

inside its vessel. A poet’s very blood is words.

How do we build these amazing things?

There are many ways in which you might begin to write – many ways in which you

might be ‘ambushed’ by the Muse. To discuss them all (as I would like to) would

mean an essay of great ( and possibly e n d l e s s ) length,

so I content myself (for the purpose of this piece) with documenting how a poem

of mine came about, via one of these muse facets –

Muse Apparently Callous.

ii

How do poems begin? They aren’t butterflies – don’t flit about the place

like beautiful moments, palps dripping nectar’s verse – don’t light upon you

just because they sense an upturned face. They creep up on you in the dark,

eerie, stealthy, intrusive, apocalyptic – when you’re late for the dentist,

in a meeting, on the loo. When your mind is an alleyway, they spill cold

breath down your neck. Give you shudders. Give you goosebumps. Come

at you violently alive. Give you thrills. Poetry is not convenient. Nor is it

polite. It doesn’t wait until you have finished whatever it is you must do.

(CAUTION: the following aspect of my relationship with Muse Apparently

Callous may shock, or cause offence)

If my head is an overturned stone, then poetry is the woodlice swarming on it.

It will disrupt sleep, meals, baths, conversations, a strict or sombre occasion

when it might seem wrong to wield a pen. I remember the poem that hassled

its way into my mind at a funeral. No, no! I whispered – which sounded

occasion-relevant, at least. I am not making light of what was a serious,

traumatic occasion. I am nowhere near as callous as poetry, though admitting

that it claimed the largest part of my head that day might make me seem

to be so. Words threw themselves at my brain like hail. I wanted to be left

alone – there was so much around me to process. I wanted the comfort

of a soft cloth stim, so I reached for my handkerchief. Of course there was

a pen. I am under the thumb of poetry. I carry one, no matter where I am.

Its nib glinted. The poem became a physical pain. I had no paper, except

the memorial booklet, its portions of unfilled space. It was Lockdown –

most of the mourners were outside. I was standing on the periphery, alone.

My head ached with the pressure of resisting. My fingers fought to answer /

deny poetry’s urge. I have, to my chagrin, ignored these poetical visitations

before. The Muse is abstruse, is a will-o’-the-wisp. Capture it or pay

the price later, in empty pages, hauntings and regret.

iii Allow me, perhaps, to justify.

Poetry is very much two sides of a coin for me. If I’m not producing work, stress

rapidly accumulates. I believe I have lost my means of expression. If I cannot

articulate / process what I am seeing / thinking / feeling then I quickly

become angry / confused / frustrated. Go catastrophic within an hour –

I’m losing my voice aren’t I I am going to forget

who I am people are going to forget who I am and

the urge to scream out loud is taking hold I cannot

be still my hands must be filled with actions I am

aware of the agony in my head I must I must

And if I am writing? Joy —— Fear / Ecstasy —— devastation. In the

space, the subtle hinterland between each opposite place, is poetry. During the

occupation of this space,

urgency.

Productivity.

Burnout.

Fatigue.

Obsessive hyper-production.

Self-expression.

Freedom.

Truth.

A way of being.

iv

Muse doesn’t offer many second chances – if I don’t grasp these flashes

there and then, I forget what they were trying to tell me, am left with only

the hazy trace of them in my mind, not the words or form. Nothing remains

but the overwhelming suspicion something crucial has been lost. One poem

will even gatecrash another, and say hey! This is MY party, or three come

at once, like insolent buses. A poem will hide from you when you most need it.

You’re not the boss of me. I’ll take my own sweet time, it fleers. Poetry is master

of the inopportune. Poetry, more often than not, is a bit of a shit.

v

Thwarted Belongingness was very much at the forefront of my mind at the time

of my friend’s death (you will find, should you need it, a brief explanation below).

The seemingly endless relearnings / researchings of self

I have endured over the last three years often expose something so raw I find it

hard to assimilate / concentrate on anything else.

Thwarted Belongingness was one such ‘discovery’ – its theory (as I saw it)

of ‘unbelonging’ and the distress / confusion / weariness connected

to this state began feeding into every aspect of life. I became ill, for a while,

recalling the many times I have endured suicidal thoughts and this was occupying

my mind at the same time that I heard the news of my friend’s death.

It certainly influenced my participation in my friend’s own ‘ceremony of

unbelonging’, which I catalogued, courtesy of Muse Apparently Callous,

step by step through each stage. The funeral came to me in a series of glimpsed

fragments and the poem’s form reflects this. In subverting the guilty / hasty snatches

I recorded during the funeral service, they appear, in the final product,

as moments of introspection / repentance.

The white space operates as moments of pause –

between ‘segments’ are representations of breath,

of the moment it took to focus,

become aware of the microcosmic vignettes

unfolding, before unfocusing again.

The ‘processional’ feel of the funeral, the stolen glances, fighting the urge

to stare, the portioned, scene-by-scene operations render the poem stilted

and strange, as was the day itself.

I wondered if my friend was there – are we just…gone, or are we ever really

dead? Are we shifted on to somewhere else? Was I wrong to write under such

circumstances? Weighing the appropriate is not my superpower. My friend was

very successful in business, with fingers in an extraordinary number of pies.

He was never one to let an opportunity pass him by.

I tell myself he would have wanted me to grasp the poem with both hands.

Perhaps none of this really matters and the poem was a way to help me try

to make sense of / try to connect with

a friend’s death. Was it wrong of me? I do not know.

Ultimately, I have a strong impression of having built my friend

a memorial of my own. After the poem was released from my head,

I found peace.

Does anything, in the end, belong to anyone?

Whatever the answer may be,

here is the poem.

Thwarted Belongingness

a car rolls past hushed and sleek & all stiff colloquies hush

at the sight of its elongated dark drizzle clings to its long roof

like a coat of pearls that only moments ago belonged to the sky

a spray of orchids almost as l o n g as the casket’s lid

& our tall friend somehow folded up inside none of them

belong anymore to blood or soil the blooms sham life

when they are brought into the bitter day how small death

has made him what happened to the size of his laugh

we all stand in our own wheels of space & all I want

is to ruin the immaculate glass with the glyph of my damp palm

& blur my view of the box that once belonged to living oak

all I want is to tell him time to get up & see him duck the lintel

of our door again I see his weeded wife & I am amazed at how

she stands her black chiffon flies like a tail no longer

attached to the bird everyone remembers how he loved to sail

an umbrella domes the name of some brewery in The Lakes so many

signs of water puddles the shape of Buttermere Red Tarn

leaves falling like soft prophets mark the silver

with mild green boats each no longer part of the whole crown

a voice turned metal by tannoy says join in the chorus

the words are in the memorial book & he is smiling on the cover

I lay my finger over his jaw without his grin his face is only

a plain shell We’ll meet again there are cracks in the way

we all sound & the salt woe on a mourner’s cheek is no longer

a part of their eye a pigeon grey and lone settles

the chapel’s ridge its wings no longer part of flight I look past

where a stone crop grows above where human seeds are sown

as I sang my mouth filled with rain & the wind took

each word as it leapt from the edge of my lip & the sigh

that I made was no longer part of my breath

iA Poem Begins?

Poetry is a laser beam to the brain / a raw vein leading straight to the heart.

We find a poem that affects us that we love and we resonate inside its vessel.

A poet’s very blood is words. How do we build these amazing things?

There are many ways in which you might begin to write – many ways in which you

might be ‘ambushed’ by the Muse. To discuss them all (as I would like to) would

mean an essay of great (and possibly endless) length, so I content myself (for the

purpose of this piece) with documenting how a poem of mine came about, via one of

these muse facets – Muse Apparently Callous.

ii

How do poems begin? They aren’t butterflies – don’t flit about the place like beautiful

moments, palps dripping nectar’s verse – don’t light upon you just because they sense

an upturned face. They creep up on you in the dark, eerie, stealthy, intrusive,

apocalyptic – when you’re late for the dentist, in a meeting, on the loo. When your

mind is an alleyway, they spill cold breath down your neck. Give you shudders. Give

you goosebumps. Come at you violently alive. Give you thrills. Poetry is not

convenient. Nor is it polite. It doesn’t wait until you have finished whatever it is you

must do.

(CAUTION: the following aspect of my relationship with Muse Apparently Callous

may shock, or cause offence)

If my head is an overturned stone, then poetry is the woodlice swarming on it. It will

disrupt sleep, meals, baths, conversations, a strict or sombre occasion when it might

seem wrong to wield a pen. I remember the poem that hassled its way into my mind at

a funeral. No, no! I whispered – which sounded occasion-relevant, at least. I am not

making light of what was a serious, traumatic occasion. I am nowhere near as callous

as poetry, though admitting that it claimed the largest part of my head that day might

make me seem to be so. Words threw themselves at my brain like hail. I wanted to be

left alone – there was so much around me to process. I wanted the comfort of a soft

cloth stim, so I reached for my handkerchief.

Of course there was a pen. I am under the thumb of poetry. I carry one, no matter

where I am. Its nib glinted. The poem became a physical pain. I had no paper, except

the memorial booklet, its portions of unfilled space. It was Lockdown – most of the

mourners were outside. I was standing on the periphery, alone. My head ached with

the pressure of resisting. My fingers fought to answer / deny poetry’s urge. I have, to

my chagrin, ignored these poetical visitations before. The Muse is abstruse, is a will-

o’-the-wisp. Capture it or pay the price later, in empty pages, hauntings and regret.

iii Allow me, perhaps, to justify.

Poetry is very much two sides of a coin for me. If I’m not producing work, stress

rapidly accumulates. I believe I have lost my means of expression. If I cannot

articulate / process what I am seeing / thinking / feeling then I quickly become angry /

confused / frustrated. Go catastrophic within an hour –

I’m losing my voice, aren’t I? I am going to forget who I am – people are going to

forget who I am and the urge to scream out loud is taking hold. I cannot be still.

My hands must be filled with actions. I am aware of the agony in my head. I must…

I must…

And if I am writing? Joy – Fear / Ecstasy – Devastation. In the space, the subtle

hinterland between each opposite place, is poetry. During the occupation of this space

urgency. Productivity. Burnout. Fatigue. Obsessive hyper-production. Self-expression.

Freedom. Truth. A way of being.

iv

Muse doesn’t offer many second chances – if I don’t grasp these flashes there and

then, I forget what they were trying to tell me, am left with only the hazy trace of

them in my mind, not the words or form. Nothing remains but the overwhelming

suspicion something crucial has been lost. One poem will even gatecrash another,

and say hey! This is MY party, orthree come at once, like insolent buses. A poem will

hide from you when you most need it. You’re not the boss of me. I’ll take my own

sweet time, it fleers. Poetry is master of the inopportune. Poetry, more often than not,

is a bit of a shit.

v

Thwarted Belongingness was very much at the forefront of my mind at the time

of my friend’s death (you will find, should you need it, a brief explanation below).

The seemingly endless relearnings / researchings of self I have endured over the last

three years often expose something so raw I find it hard to assimilate / concentrate

on anything else. Thwarted Belongingness was one such ‘discovery’ – its theory

(as I saw it) of ‘unbelonging’ and the distress / confusion / weariness connected

to this state began feeding into every aspect of life. I became ill, for a while,

recalling the many times I have endured suicidal thoughts and this was occupying

my mind at the same time that I heard the news of my friend’s death.

It certainly influenced my participation in my friend’s own ‘ceremony of

unbelonging’, which I catalogued, courtesy of Muse Apparently Callous,

step by step through each stage. The funeral came to me in a series of glimpsed

fragments and the poem’s form reflects this. In subverting the guilty / hasty snatches

I recorded during the funeral service, they appear, in the final product, as moments

of introspection/repentance.

The white space operates as moments of pause – between ‘segments’ are

representations of breath, of the moment it took to focus, become aware of the

microcosmic vignettes unfolding, before unfocusing again.

The ‘processional’ feel of the funeral, the stolen glances, fighting the urge

to stare, the portioned, scene-by-scene operations render the poem stilted

and strange, as was the day itself.

I wondered if my friend was there – are we just…gone, or are we ever really

dead? Are we shifted on to somewhere else? Was I wrong to write under such

circumstances? Weighing the appropriate is not my superpower. My friend was

very successful in business, with fingers in an extraordinary number of pies.

He was never one to let an opportunity pass him by.

I tell myself he would have wanted me to grasp the poem with both hands.

Perhaps none of this really matters and the poem was a way to help me try

to make sense of/try to connect with a friend’s death. Was it wrong of me?

I do not know. Ultimately, I have a strong impression of having built my friend

a memorial of my own. After the poem was released from my head, I found peace.

Does anything, in the end, belong to anyone? Whatever the answer may be,

here is the poem.

Thwarted Belongingness

a car rolls past / hushed and sleek / & all stiff colloquies hush

at the sight / of its elongated dark / drizzle clings to its long roof

like a coat of pearls that / only moments ago / belonged to the sky

a spray of orchids / almost as / l o n g / as the casket’s lid

& our tall friend somehow / folded up inside / none of them

belong anymore / to blood or soil / the blooms sham life

when they / are brought into the bitter day / how small death

has made him / what happened / to the size of his laugh

we all stand in our own / wheels of space / & all I want

is to ruin the immaculate glass / with the glyph of my damp palm

& / blur my view of the box / that once / belonged to living oak

all I want is to tell him / time to get up / & see him duck the lintel

of our door / again / I see his weeded wife / & I am amazed at how

she stands / her black chiffon / flies like a tail no longer

attached to the bird / everyone remembers how / he loved to sail

an umbrella domes the name / of some brewery in The Lakes / so many

signs of water / puddles the shape of / Buttermere / Red Tarn

leaves / falling / like soft prophets / mark the silver

with / mild green boats / each no longer part / of the whole crown

a voice turned metal by tannoy says / join in the chorus

the words are in the memorial book / & he is smiling on the cover

I lay my finger over his jaw / without his grin / his face / is only

a plain shell / We’ll meet again / there are / cracks / in the way

we all sound / & the salt woe on a mourner’s cheek / is no longer

a part / of their eye / a pigeon / grey and lone / settles

the chapel’s ridge / its wings no longer part of flight / I look past

where a stone crop grows / above where / human seeds are sown

as I sang / my mouth filled with rain & / the wind took

each word as it leapt from the edge of my lip / & / the sigh

that I made / was no longer part of my breath

Thwarted Belongingness is used as part of a suicidality assessment tool for autistic people. Thwarted Belongingness is a mental state that worsens when the need for connectedness and belonging is not met. Studies have shown that autistic people are at more risk of suicidal thoughts compared to not autistic people.[1]Cassidy, S.A., Bradley, L., Cogger-Ward, H. et al. Development and validation of the suicidal behaviours questionnaire – autism spectrum conditions in a community sample of autistic, possibly … Continue reading