Chris Edgoose reviews Bioluminescent Baby by Fiona Benson (Guillemot, 2021)

“And crawling on the planet’s face / some insects called the human race … / lost in time and lost in space / and meaning” – The Rocky Horror Show

In 2019, Carol Ann Duffy, in her last act as Poet Laureate, brought together a selection of insect-themed poems by contemporary poets in order to highlight the importance of insects to Earth’s ecosystems, as well as exemplifying poetry’s role in environmentalism: “Everything that lives is connected and poetry’s duty and joy is in making those connections visible in language” she wrote.

The selection’s quality was, as you would expect, extremely high, and ‘Love Poem, Lampyridae’, the opening poem of Fiona Benson’s new collection Bioluminescent Baby, was one of the standouts. Like the collection as a whole, it takes us into the behavioural minutiae of these fascinating creatures (and Benson’s own enthralled amazement comes through in every line) before pulling us back out into the human world to ruminate on the similarities between the two and make the connections Duffy talked about.

In some poems the parallels are individual and personal (“I too”, “my own soul”), while others, as in ‘Love Poem, Lampyridae’, about the nocturnal attraction of the male by the female glow-worm, serve a wider, more emphatically environmental purpose. At the end of the poem, Benson cleverly doubles up the metaphorical layers of light and dark so that the glow-worms’ carpe diem (or carpe noctem?) becomes both an observation on the evolution of human thought and a sinister warning as to where that evolution may lead:

Once were humans wandered in the lanes,

led astray by fairies, foxfire, who found

their stranger selves and brought them home.

Now the dark is drowned, but some things

you can only find beyond the light,

and it is time and almost dawn and love,

my love, there is no finding then.

There is much to love about and learn from this collection. Not only has Benson been writing about insects for a long time, she has also thoroughly researched her work, and so she knows what she’s doing. The observations of insect life are expertly and economically rendered so that we read them almost as we might observe the insects for ourselves through a microscope, as here, in ‘Caddisfly Larvae’, where a Caddisfly larva emerges from its chamber:

Feelers extrude

like tobacco shreds

from a roll-up cigarette.

The nymph hauls out,

its lemon belly

feathery with gills

like an exposed nerve,

a tender knuckle

emerging from its foreskin,

pleasure branching.

The poet makes extensive and inventive use of simile to help achieve this microscopic effect (“like an ecstatic gymnast”, “like a train with two engines”, “like rainbowed cellophane”, “like quick spirits rushing”), with the “likes” proliferating and piling up in some poems to an extent which in another context would be bothersome but here seems appropriate, as though the similes themselves are insects within the nests of the poems’ wider metaphors.

The observations of insect life are expertly and economically rendered so that we read them almost as we might observe the insects for ourselves through a microscope

Benson is also a skilled prosodist and the patterns of rhythm that her poems build, with her subtle part-rhyming, also contributes to the connection we feel with these animals in almost every poem. Here, in the nine-poem sequence ‘Notes towards an Understanding of Butterfly Wings’, we sense the pulse and flow of life in every cell of a butterfly, particularly emphatic in the beat of the repeated trochees in the final couplet:

Here is your wing

in Methylene blue.

The tracheal tube

breathes in and out

like the ocean.

[…]

Here at your scent pad’s crux

a heart-shaped pump.

(from ‘Notes towards an Understanding of Butterfly Wings – 6. Notes: Blue Stain Revelations’)

Evoking this intangible sense of a creature’s ‘lifeforce’ is of course part of the ‘duty and joy’ Duffy mentioned, and is something scientific writing cannot achieve on its own. This is where collaboration between researchers and poets gives rise to a new and unique view of the intersection between human and non-human life. Benson’s success in providing this view is one of the main reasons for the success of the collection.

But it is not the only one. Benson’s theme is principally love and motherhood, and taking the often-overlooked strength, beauty and grace of insects as a metaphor for these things is a powerful central conceit. And a particularly apt one, as female insects are so often bigger and more powerful (and frankly more important) than males. They are a class of animal which seems to carry the feminist message in their very genes.

Although Benson is clearly a humanist and a Darwinian, her careful, loving descriptions now and then carry a tone of reverence which suggests that her wonder and joy at nature runs very close to sanctifying it

The ‘I’ of the poems can, I think, generally be taken for the poet herself, but this is not always entirely clear as both human and insect females experience the instinctual pull to attract the male (the first person of “If I spin for you / will you come?” in ‘Mayfly ii Imago’ could be interpreted as both a human and an insect voice, especially coming as it does between two third-person poems in this three-poem sequence).

And it is often the case that the attributes of the insects and their behaviour cause the poet to reflect on her own protective and procreational instincts: “I too keep guard – / my daughters // the softest part of me” she says in ‘Blue Ghost Firefly’; and in the collection’s final poem ‘Field Crickets’ as a male scientist passes her an insect she feels the brief brush of his finger against her palm and experiences “that giddy inwards swoop, its pheromone wash / its compulsion”; and later when she returns to the lab and all the hundreds of crickets under observation have died, she begins to “be dizzied by the whole whirling circuit / these desperate spells of singing and fucking and laying and death”, reflecting on how “(m)y single self sickens, understanding itself / as a slave to DNA”. As so often in Bioluminescent Baby, not only is the human elided into the insect, but the individual is elided into the entire species.

There is also a curious ‘almost’ elision of the scientific and the spiritual, and although Benson is clearly a humanist and a Darwinian, her careful, loving descriptions now and then carry a tone of reverence which suggests that her wonder and joy at nature runs very close to sanctifying it. One of the things she seems to be asking is at what point does love end and worship begin. In ‘Wasp Theology’ she links this “unusual deference” to fear, in this case the fear of the “paper balloon” of a wasps’ nest in a garden shed – a “tabernacle” containing a “holy monstrance” – but her language suggests that it is within such natural phenomena that the claims and metaphors of religion are appropriate. The nest is the wasps’ nursery

for the body of their Christ,

and all these black and yellow flames

are a thousand simmering tongues,

solicitous beings,

manifesting brood,

substantiating summer light.

(from ‘Wasp Theology’)

The wasps may be creating their own Christ, but they are creating a real thing, a physical substance from nothing other than what comes from sunlight, and herein lies the sense of awe in the face of the unknown which I think Benson refers to later, on considering the “spent purse” of a dead mayfly, in the line “what survives is code”. Here there is an obvious and simple genetic meaning of course, but a ‘code’ is also a secret system or a mystery, and you might go so far as to say that the word ‘code’ implies a ‘codemaker’ as well as a ‘codebreaker’ (though even scientific language suffers from limitations in our ability to describe naturally selected phenomena).

LOVE POEM, LAMPYRIDAE

Lampyris noctiluca

The female born again with little changed

except she has no mouth and may not eat,

except she has this urge to climb, this light

she must raise and twist; the male born again

with little changed except he has no mouth,

except he has this urge to search, and wings –

oh she must twist and turn her tail’s green fire

like bait, its little stab of brightness in the night,

and he must search with wings through troubled air

to find her pinhole lure, its single, green,

seducing star … All night she signals him in:

come find me – it is time – and almost dawn;

all night he looks for her in petrol stations,

villages and homesteads, the city’s neon signs:

where are you – it is time – and almost dawn …

For all the detailed observation, scientific rigour and careful research that this collection exudes, there is something here, something Benson’s language draws us closer to, which sits behind the science. We are kept from this by our limitations as organic, instinctual, biological machines – “oblivious and captive, all of us messengers – / we think we have meaning but already biology has done with us …”. This is again from the collection’s awesome final two-part poem ‘Field Crickets’, which ends with a beautiful section echoing the end of Darwin’s Origin of Species, the famous “It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank” paragraph.

Benson has noted how she “bear(s) the message / of both (her) grandmothers’ bodies” and this leads her to

(t)hink of that butterfly migration across oceans and deserts

completed in stages – how each butterfly undertakes

a section of the journey, then lays its eggs and dies

[…]

a sort of relay across the honeyed distances, across time.

Again, the individual gives way to the species, but there is Darwinian ‘grandeur’ in the idea of being part of something greater than oneself, and there is joy in reflecting (in being able to reflect) on this: “how much I love the meadow / turning under them, its tapestry of grass and wort and vetch / stitching and re-stitching green, its endlessly mutating song.”

So we see the female of the species as the messenger, the carrier of the genetic code, and as the dangerous protector (“coiled around your eggs, // like a diminutive dragon / guarding your hoard” in ‘Blue Ghost Firefly’). But Benson also plays on the imagery of witchcraft – that most contemporary and potent repository of symbols for female empowerment – to evoke and redraw the much-unloved earwig (“Forked mother, how you stoke your cauldron” in ‘Earwig’), and composes a love-song list of all the reasons to adore the female cockroach and rescue her from almost universal revulsion (“Someone must care for the dirt” in ‘Mama Cockroach, I Love You’).

Fiona Benson is not the first person to exploit the metaphorical potential of insects, and she won’t be the last, but she does it extremely well. I would highly recommend Bioluminescent Baby to anyone who wants to see just how effectively poetry can make the connections between human and non-human life on Earth visible in language

In this multi-layered collection, there are still other poems which carry the human-insect connections in a different direction. In ‘Marmalade Hoverfly’, the insects are on a “migrant flight… // towards a warmer meadow”, which of course refers to an annual migration, but the poem is positioned directly after ‘Wax Moths’, a fascinatingly concrete poem in which these parasitical creatures are described as “fat colonials / fleeing (the beehive) / with / their spoils / on grey and graceless / homicidal / wings.” It is difficult not to read both these poems, at least in part, as comments on contemporary political debates around history and Empire.

In the end, though, it is the bond or pull between mother and child that lies at the centre of the collection, and whatever name we choose to give it, it is the strength of this connection that Bioluminescent Baby celebrates. ‘Marmalade Hoverfly’ ends with a reflection on how an insect’s call to fly the “thousands of miles (to) / where their young will thrive”, a mother’s drive to protect her children, and every human’s compulsion to try and understand the world around them, are all, ultimately the same thing:

call it the fierce insistence

of our own genetic code,

call it love.

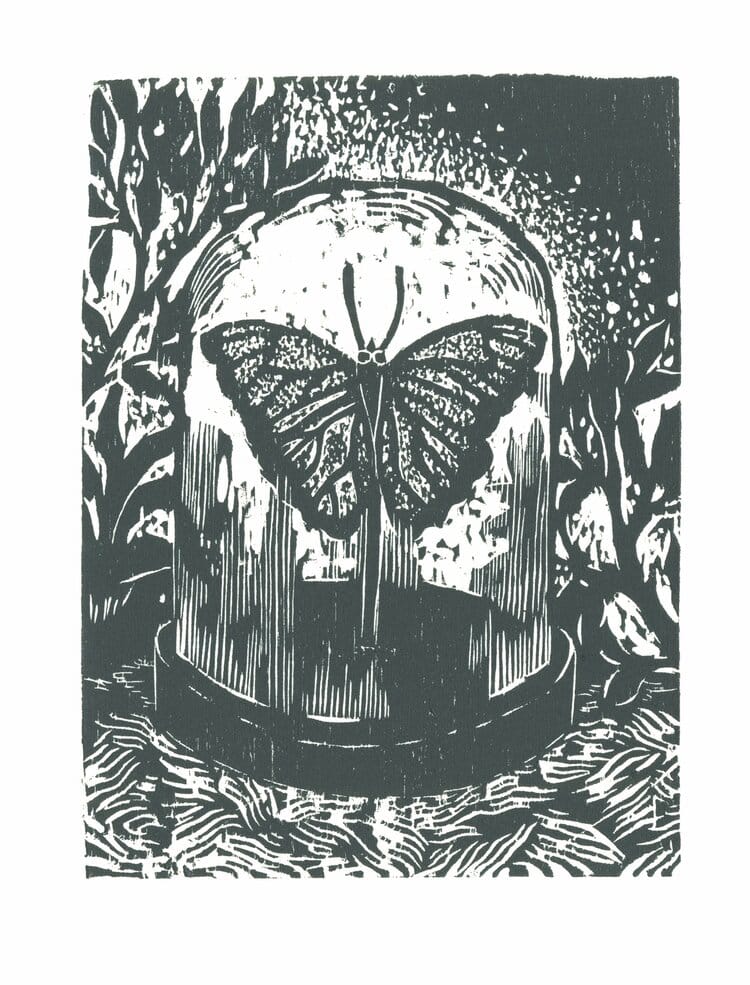

It is also, finally, worth noting that the collection is beautifully illustrated with woodcuts by Anupa Gardner. These have the interesting and very appropriate effect of giving the occasional impression that you are reading an old-fashioned children’s book; but they also of course add tonally to the poems they appear beside, drawing you in to the insects-eye-view and emphasising the themes of light and dark that are so central throughout.

Fiona Benson is not the first person to exploit the metaphorical potential of insects, and she won’t be the last, but she does it extremely well. I would highly recommend Bioluminescent Baby to anyone who wants to see just how effectively poetry can make the connections between human and non-human life on Earth visible in language.

Chris Edgoose is a poet and blogger at Wood Bee Poet. He lives near Cambridge in the UK, and has had work published in several magazines in print and online.