Michael Grieve reviews Rapture’s Road by Seán Hewitt (Penguin Books, 2024)

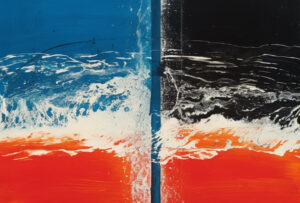

A painted hand. In its palm, a wound. Threaded through the wound, and wound around the fingers, a red snake. This is the image that greets Seán Hewitt’s readers on the jacket of his new collection, Rapture’s Road. The hand is Christ’s as painted by Hans Memling in the fifteenth century, and the snake – in such (apparently) intimate contact with Memling’s paint – is a digital addition by Robin Isley. Rather than the plural stigmata, the image highlights a singular stigma, and it is through this stigma that something contemporary – both beautiful and transgressive – snakily creeps.

Hewitt examines the stigma/wound in ‘We Didn’t Mean to Kill Mr. Flynn’. This two-part poem gives voice to Declan Flynn, killed in a homophobic attack in a Dublin park in 1982, and to one of his murderers. Both parts of the poem carry substantial footnotes that point the reader to material from the Irish Queer Archive, making the documentary reality of the murder impossible to forget. The first part, in the killer’s voice, pleads that “Maybe, that time, we went too far”, a not-apology that matters little after “it sunk in / that he was after dying”. This is as prelude to Declan himself, whose voice describes the park as “another Gethsemane”. But the park offers no biblical repose. It was “good for hiding in” and so served as a gay cruising area. This is “its blessing / and its curse” and why – like Gethsemane – it is a site of betrayal: “the trees I trusted / to cover me lent them their branches”. Flynn died, a footnote tells us, by asphyxiating on his own blood, and there are no transubstantive miracles here: “no stone rolled back, no ascension”.

But Rapture’s Road is a collection strung through with the miraculous and the diaphanous and the ephemeral. “Like a feather, I learned, the soul weighs less than it lightens” begins one untitled poem. And two poems here are called ‘Dispersion Song’. In one, a host of insects becomes a bride’s veil; in the other it seems “as though the woods / are to be newly broken, the earth split apart”. In ‘Immram’, the speaker lowers themself into water – “It threw icy hoops around me. Yes. / I felt ungendered in its arms”. This mirrors earlier untitled poems in which the speaker, an “androgyne of the garden”, raises their arms ready to put on “the gown night holds above”. In the very next poem, the speaker wears “the wind as a gown” until it “Ungenders / the shape of me – sweet seamstress / lightens the muscle of me”.

This repeated disavowal of the gendered, conventional self opens up the possibilities of identity. In ‘Immram’, “The soul, I knew, / was all plural. I could have spent / a thousand lives changing myself”. Similarly, in an untitled poem, “behind your life / there might be / other lives, waiting”. These lyrics have a mellifluous, hypnagogic quality, approaching the reader like gorgeous music half-heard while half-asleep. They do not want to be pinned down.

Rapture’s Road is a collection strung through with the miraculous and the diaphanous and the ephemeral

For me, however, it is when Hewitt gives us a pin that his lyricism achieves its most compelling effects. Take ‘Evening, with Ghost Moths’, in which the poet grieves for his father while watching the moths with their “flights of white […] and the underwing / dark”. This flickering between stark visibility and disappearance becomes “a door spinning open / then shut […] a fitful apparition undoing its sign / on the dark”. The poem reaches its heartbreaking conclusion:

I am held

like a child – my darting eyes –

waiting for you, father, to turn

your white side open, to show yourself –

The final phrases of Hewitt’s conceit throw it open to the reader. These really are ghost moths, and while they may look like “sycamore keys”, we’re faced with the fact that they will never unlock anything. Or at least not in the way he hopes.

A few poems later, in ‘Alcyone’, Hewitt consoles his mother who “All morning […] had cried in the bath / as I held her hand. Submerged // in grief’s deep water”. A kingfisher flashes by. But the poet – on the edge of comparing his mother to Alcyone (who threw herself into the sea after her husband’s death before being transformed into a kingfisher)– interrupts his own train of thought: “the image, // all beauty, stalls at the mind’s / dulled synapse”. Only the bird’s absence stands: “It passed / beyond our vision, and the sweet / water burned at its touch”.

Touch burns in many of these poems, most notably those that invite us into the half-lit world of gay sex in which Declan Flynn sought sanctuary

Touch burns in many of these poems, most notably those that invite us into the half-lit world of gay sex in which Declan Flynn sought sanctuary. “Go”, Hewitt instructs at the beginning of section II, “in the dew with your wet shoes […] to the white tissues / and the scuffed ground / and see that man, there”. He is “emptying / the animal of his body over the earth”, not unlike the young deer in ‘Whoso List to Hunt’ who are “rutting, one shadow hurled // into the next […] as they lock the cross // of their sex in place”.

When the speaker returns to the rutting site in another season, he uncovers in “the musk / of those hot glands […] a memory of violence, / its urgent expenditure”. The world of flowers also yields language of lustful force. In ‘Dogs’, for example, two men ride “a silicone piston […] with the slick glove of their own forms” and this becomes “urgent / hyacinth – regal, speared, violent”. Meanwhile, ‘Night-Scented Stock’ opens to a submissive voice (“he gripped my face in his hand // and threw me, God I wanted / to be pushed”) but as in previously mentioned poems, this giving over of self becomes its own creative act: “my name crushed // to its atoms, I made for him a word / Adam could not have said inside the garden”.

These strands are combined wonderfully in ‘Haw’, where the speaker, flirting at the edges of a cruising spot, picks hawthorn berries with which to infuse gin. Beneath his final description of the haws is the taut desire of held gaze and unspoken negotiation:

I would take

the pricked needle

like a thorn wielded back

to the fruit, would turn

the body against

its own tenderness

and violate it –

The deliciousness of this violation almost fizzes on the tongue. As an odd companion to ‘Haw’, ‘St Jude’s’ is named for the patron saint of hopeless causes. Here the speaker has claimed sanctuary in a church on Ash Wednesday and looks in despair for transformation: “I made / whatever sound it took / to call each part of myself by name / and return it to the house of song”. This rediscovery of the self comes only after a descent into “the filth // of life”.

Indeed, Hewitt’s second collection seems to direct us away from Eden into an altogether different garden, in which it is the dangerous temptation of the fruit, the slipperiness of selves and songs and sex, and the red serpent in the grass (or rather, in the hand) that might allow us to fall, not further into sin, but rapture.

Michael Grieve lives and work in Fife. He was shortlisted for the Edwin Morgan Poetry Award in 2020, and his pamphlet Luck is published by HappenStance Press. Other poems have appeared, or are forthcoming, in The Scores, Perverse, Magma, Gutter, and Bad Lilies.