Hilary Menos reviews The Process of Poetry edited by Rosanna McGlone (Fly on the Wall Press, 2023) and On Poetry by Jackie Wills (smith|doorstop, 2022)

As we said last week, The Friday Poem doesn’t normally publish costs, as they vary from site to site, but they might be relevant here if you’re trying to decide which – if any – of these books to buy. Last week we looked at Poetry Projects to Make and Do edited by Deborah Alma (Nine Arches Press, 2023) which is the most expensive at £16.99, and On Poetry by Roger Robinson (2023) which is is £10 for a digital download from Gumroad. The Process of Poetry comes in at £10.99 (on the Fly on the Wall site), as does On Poetry by Jackie Wills, though you can read this one for £1.40 if you’re happy with an ebook.

The Process of Poetry edited by Rosanna McGlone (Fly on the Wall Press, 2023) £10.99

Rosanna McGlone interviews fifteen contemporary poets, discussing the development of a poem from an early draft to its final iteration. The poets “reveal their full poetic process, sharing insights into their inspiration, influences, editing decisions and more”. As a (go on Hilary, say it) mature poet who wants to get down and play among the actual words, and doesn’t need to be told to “show not tell” or taught the fundamentals of self-care, I found real treasure here.

Paterson, the first interviewee in the book, responds honestly and thoughtfully to McGlone, and comes across as refreshingly straightforward and quite self-deprecating. I’m nodding and smiling when he says, “The basic level of poetic competence has risen a lot, because of the opportunities to learn. Alas, this has a tendency to mask the fact that you still can’t teach talent, which is currently drowned out by competence.” Perhaps stepping down as poetry editor of Picador has freed him up to speak his mind about contemporary poets more frankly. He’s interesting on form generally, and especially the sonnet: “There is an agitation between the language that you want to use and the constraints of the form, in terms of line, rhyme, rhythm and length. You don’t have enough room to put in everything you might be inclined to.” And he’s funny, too. When asked how he got into poetry, he recalls hearing the poet Tony Harrison on the telly when he (Don) was in his twenties. “And that was that,” he says, “and the rest is some kind of history. It’s Tony’s fault. He gave me the only career that pays worse than jazz.”

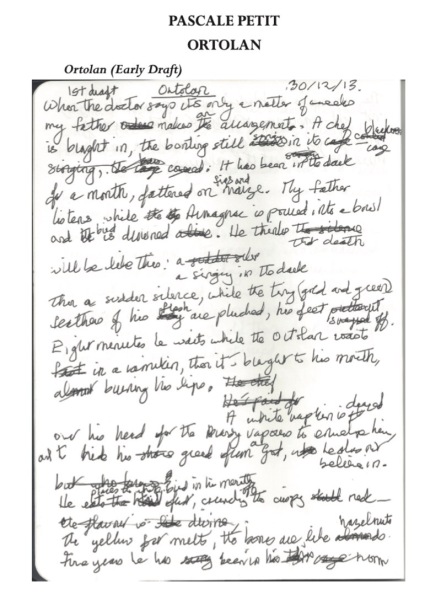

I found the story of how Pascal Petit wrote ‘Ortolan’ fascinating and compelling

I found the story of how Pascal Petit wrote ‘Ortolan’ fascinating and compelling. Her early draft is handwritten, with many scribbles and crossings out. She tells clearly and passionately how the poem came to her early one morning after she’d received a postcard from Les Murray which mentioned an ortolan – a small bird which the French eat whole, spitting out the bones, while their heads are covered with a napkin. Asked how she chose the form for the poem, she says, “I had this image of the single white cloth draping over everything, which lends itself more to a solid block of text.” She describes how how she pared the language of the poem back: “In my early notes, the napkin was ‘embroidered’, however this was irrelevant “. And she shares insights into her longer term writing process, saying, “I made a leap in my work when I discovered that you probably have to recast a poem, rather than just edit your initial draft until it becomes okay.” A tip for me to remember, I think.

Of particular interest is how different Caroline Bird’s finished poem ‘The Final Episode’ is to her first draft. Even she admits it’s not so much a first draft but personal jottings in a notebook. It’s a two-page screed which starts:

Will you forgive me in advance?

I’m not going to be like the other mums, baby,

To be honest I’m not even going to try.

They’ll be loads of things I’ll be supposed to care about

That I won’t care about. I’ll forget forms.

What will the limits of your tolerance be?

The finished poem, titled ‘The Final Episode’, starts:

The 18th century bawd who sells her daughter’s virginity

to an Earl. The tired CIA operative who says “just do it”

then half a village dies. The plantation owner’s wife.

The lonely CEO of the pharmaceutical company

who screams like a banshee when an employee’s baby

pukes milk on her pant-suit.

Bird says, “There was nothing in terms of the language that I wanted to keep from the early jottings. The one thing I wanted to preserve was that sense of disorganisation through feelings being piled on top of each other […]. The words are different, but the emotional heart of the poem is the same.” Bird is fascinating – and delightfully blunt – when she talks about how she decides which drafts to discard and which to pursue. The way she describes the process makes it sound a bit like fishing, waiting to see if the poem tugs on the line. Sometimes it just goes slack. “When that happens, you can rewrite it as much as you like, make it look as neat as you like, make it look beautiful,” she says, “but it’s like giving mouth-to-mouth to a log.” Ha!

Part of the joy of a book like this is finding where poets disagree. On truth, for example …

All of the poets interviewed here are fascinated by craft and are happy to get into the nuts and bolts of it. John McCullough talks in detail about particular words he changed as his poem progressed, and why. He says, “For example, ‘press’ becomes ‘slow chafe’, which is a more sensory image and ‘suddenly’ becomes ‘wildly’, which creates an emotional punch because of its contrast with the earlier, flatter tone. I replaced ‘click’ with ‘snicked’, as it works much better sonically.” Liz Lochhead, on making changes, says, “Sometimes you can’t explain to yourself why you’ve made a change, all you can say is you did so because you like it better. Simple as.”

Part of the joy of a book like this is finding where poets disagree. On truth, for example, Gillian Clarke says “The truth is crucial. I never tell lies in poems, never. I don’t use false description to get a line. It won’t convince if it isn’t real.” Victoria Kennefick says, “I suppose there’s real truth on a personal level, what actually happened, but then there’s poetic truth and I’m really interested in the space between those two realities. There’s a point where you, as an individual, have to let go of the truth of the event, to allow the truth of the poem to take over.” And Sean O’Brien says, “The fact that something is true doesn’t make it interesting.”

On Poetry by Jackie Wills (smith|doorstop, 2022)

Where Deb Alma’s Poetry Projects to Make and Do offers an eclectic collection of essays on a variety of directions poets might take, Jackie Wills focuses on writing for the page. Where Roger Robinson exhorts, Wills speaks quietly and humbly. And where The Process of Poetry talks to fifteen different contemporary poets, with varying processes and occasionally conflicting opinions, Wills’ book has a clear single voice. On Poetry is careful, considered, thoughtful, and full of insight and wisdom. It doesn’t read as if it has been written to be published, or to be fashionable, or to make a quick buck. It reads as if it has been written to be read, to forge a connection with a serious reader.

The first part of the book is part hands-on how-to-write and part reflection on ways that poetry can make a difference to how we live. It is also a survey of many varied and inspirational writers, especially (but not only) women poets, especially from the end of the 20th century. The second part of the book is a guide to running writing workshops which covers planning workshops, preparing workshop materials, writing exercises and prompts, and using model poems in writing exercises. She says, “I used model poems in writing exercises because a mechanic learns to put an engine together by taking it apart. A poem has to be oily and heavy too.” There’s a chapter on working in schools and colleges where Wills gives a couple of fascinating case studies and talks about running workshops for primary and secondary school-age children and pupils with special educational needs. She has considerable expertise in this area, with decades of experience as a poet and tutor, and it shows. She illustrates some of the exercises with poems, including an absolute scorcher from Catherine Smith, ‘Zephyr’, a poem which uses a car – the Zephyr – “that fuck-off hulk of a motor / you bought for three hundred quid / from a Birmingham art student, 1979; / two tons of scratched black metal” – to express the urgency of sex at 17, and freedom.

I found Wills to be an inspirational guide. She is not writing exclusively for women, but many of the poems she quotes or references are by women, and have the business of women as their subject matter. She says, “When I began writing I was troubled by the notion of an objective and single canon, and it was still being pushed as a standard of quality. It manifested itself in lists of white men. It set me up for feeling I’d failed […]. Thankfully, reading taught me a canon is personal, not learned”. She then shares with us her own personal canon, with poems from Elma Mitchell, Syvia Plath, Selima Hill, Grace Nichols, Olive Senior, and many more. Reading this book reminds me of how exciting the 1980s was, in terms of both politics and literature, and how important it is for me to reconnect with the long tradition of women’s writing and poetry.

On Poetry is careful, considered, thoughtful, and full of insight and wisdom

Wills writes particularly engagingly on Selima Hill, and especially on Hill’s poem ‘Being Fifty’, a poem which addresses ageing, HRT, and the voicelessness of the older woman. Wills says, “if there’s anyone at the bottom of the social pile, regardless of ethnicity, it’s an ordinary woman who’s no longer of childbearing age.” Hill’s poems, she says, help her focus her “fury”. I found it liberating (as an older woman no longer of childbearing age) to read this. Wills is generous too. She quotes a poem – ‘Lapwings’ – by Alison Brackenbury, and analyses it scrupulously, writing about how the poet achieves her effects. The poem is in couplets, and Wills examines form, rhyme, assonance, metaphor – the tools all poets need to hone their craft. On Brackenbury, she says, “What she gives her readers is sheer dedication to the craft and exquisite detail”.

This book is, for me, a much more consuming affair than the other books. It’s a slow read, and it made me stop and think often, particularly about my own way of writing. And oh my goodness what joy, she’s not afraid to use words like ‘gerund’ and ‘hendiadys’. She doesn’t dumb down. She expects a reader to stretch to meet her, and she’s humble enough to admit that she too must read more, think more, and stretch herself in the service of poetry.

On Poetry is worth £1.40 of anyone’s money for the ebook, no question, and for the more demanding and reflective poet it is worth every penny of the £10.99 paperback price.

I also have to put in one small plug here for the book that I found invaluable in my poetry practice, Writing Poems by Peter Sansom (Bloodaxe, 1993). Cliff Yates says it’s the Haynes Manual for Poetry. There’s no greater compliment. If you’re only going to buy one book on writing poetry, buy this one.

Hilary Menos is editor of The Friday Poem. Buy her most recent pamphlet, Fear of Forks (HappenStance Press, 2022).