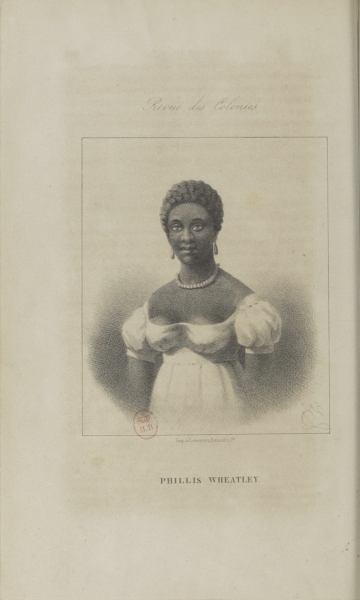

Transported as a slave from West Africa to America when just a child, Phillis Wheatley published in 1773, at the age of twenty, her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. Vincent Carretta takes a look at the remarkable life of the first ever African-American woman to be published.

The African-American poet Phillis Wheatley has achieved iconic status in American culture. A 174-word letter from her to a fellow servant of African descent in 1776 sold at auction in 2005 for $253,000, well over double what it had been expected to fetch, and the highest price ever paid for a letter by a woman of African descent. Elementary, middle, and high schools throughout the United States bear her name. A prominent statue in Boston memorializes her. Wheatley is the subject of numerous recent stories written for children and adolescents. Googling “Phillis Wheatley” turns up about 665,000 items.

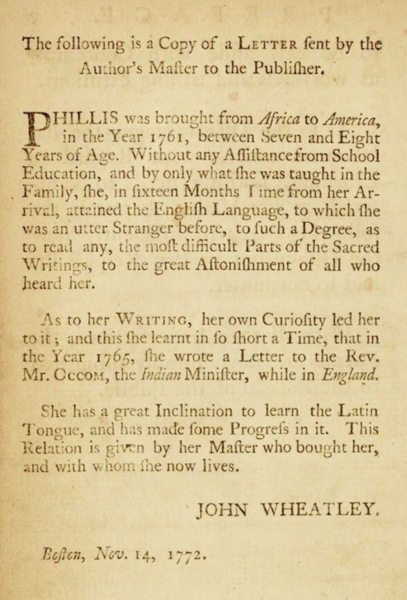

The author we now know as Phillis Wheatley was born around 1753 somewhere in West Africa, probably between present-day Gambia and Ghana. She was forced to endure the Middle Passage from Africa to America when she was about seven or eight years old, and brought to Boston, where she was sold as a domestic servant to John and Susanna Wheatley. They called her Phillis, after the name of the slave ship that brought her from Africa. Encouraged by her owners, Phillis Wheatley quickly became literate and began writing poetry that soon found its way into local newspapers. Notwithstanding the prejudices against her race, social status, gender, and age, Wheatley became the first published woman of African descent in 1767. She gained international recognition with her funeral elegy on the death of the evangelist George Whitefield, addressed to his English patron, the Countess of Huntingdon, and published in Boston and London in 1770. By 1772, Wheatley had written enough poems to enable her to try to capitalize on her growing transatlantic reputation by producing a book of previously published and new works. Unable to find a publisher in Boston, in part because of racial prejudice, Wheatley and her owners successfully sought a London publisher and Huntingdon’s patronage in 1773 for her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral.

Phillis Wheatley’s trip to London with her master’s son to arrange for the publication of her book was a turning point in her personal and professional lives. Her six-week stay in London enabled her to establish a network of associations that included many of the militarily, politically, religiously, and socially most important people in North America and Britain. She arrived in England a year after a court decision declared that slave owners could not legally compel their slaves to return to the colonies. Phillis returned to Boston shortly before her book was published. Within a month of her return she wrote a friend that she had been freed “at the desire of my friends in England.” She had apparently agreed to return only after her owner was compelled to promise to free her if she did.

Wheatley does not hesitate in ‘Poems‘ to proclaim her African heritage

The assertiveness that Phillis probably displayed in her dealings with Nathaniel Wheatley was anticipated more subtly in her Poems. Wheatley does not hesitate in Poems to proclaim her African heritage. Her opening poem, “To Maecenas”, thanks her unnamed patron, loosely imitating Classical models such as Virgil and Horace’s poems dedicated to Maecenas, the Roman politician and patron of the arts. Emphasizing in a footnote that the Classical Roman poet Terence “was an African by birth”, Wheatley implies that her “Maecenas” has enabled her to claim a place in the Western literary tradition, which has included Africans since its beginning. Elsewhere in her poems, Wheatley appropriates the persona of authority or power normally associated with men and her social superiors. For example, in “To the University of Cambridge, in New-England”, first composed when she was about fifteen years old, Wheatley speaks as a teacher to students, or a minister to his flock, in addressing the young men of what was to become Harvard University, many of whom were being trained there to become ministers themselves.

Several of Wheatley’s poems demonstrate a nuanced treatment of slavery unrecognized by some of her critics. For example, written in October 1772 to celebrate Dartmouth’s appointment the previous August, “To the Right Honourable WILLIAM, Earl of Dartmouth, His Majesty’s Principal Secretary of State for North America, &c.” is one of the most carefully crafted poems in the 1773 volume. In it Wheatley re-appropriates the concept of slavery from its common metaphorical use in the colonial rhetoric of discontent, which described any perceived limitation on colonial rights and liberty as an attempt by England to “enslave” (white) Americans. Wheatley appears to use slavery in this conventional sense in the poem:

No more, America, in mournful strain

Of wrongs, and grievance unredress’d complain,

No longer shall thou dread the iron chain,

Which wanton Tyranny with lawless hand

Had made, and with it meant t’enslave the land.

But Wheatley’s reference to her authority to speak against this conventionally metaphorical slavery reminds her readers of the reality of chattel slavery trivialized by the political metaphor:

Should you, my lord, while you peruse my song,

Wonder from whence my love of Freedom sprung,

Whence flow these wishes for the common good,

By feeling hearts alone best understood,

I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate

Was snatch’d from Afric’s fancy’d happy seat

[…]

Such, such my case. And can I then but pray

Others may never feel tyrannic sway?

Having gone to England as an enslaved African Briton, Wheatley returned to the colonies prepared to embrace the free African-American identity that the American Revolution soon made available to her. Her anti-slavery stance became more overt once she was free, compared to her poems published while she had been enslaved. She denounces slave owners as “Modern Egyptians” in a letter to the Indian Presbyterian minister Samson Occom that was widely reprinted in newspapers in March 1774 throughout New England, as well as in Canada. Wheatley increasingly came to believe that the colonial struggle for freedom from Britain would lead to the end of slavery in the former colonies. In her poem “To His Excellency General Washington” Wheatley pledged her allegiance in 1776 to the revolutionary cause, hoping that even the most eminent slave owner in North America would ultimately apply the revolutionary ideology of equality and liberty to people of African as well as European descent. In the poem “On the Death of General Wooster”, included in a letter to Wooster’s widow, Mary, on July 15, 1778, Wheatley exclaims, “But how, presumptuous shall we hope to find / Divine acceptance with th’Almighty mind— / While yet (O deed ungenerous!) they disgrace / And hold in bondage Afric’s blameless race?”

The hopes that Wheatley brought home with her from England were soon frustrated. She did not live to see the enfranchisement of her fellow people of African descent. Nor was she able to publish a second volume. Susanna Wheatley died within months of Phillis’s return from London, and John Wheatley died in 1778. Eight months later, Phillis married John Peters, a free black, on Thanksgiving Day. Although the marriage of Phillis and John Peters was initially prosperous, they soon fell victim to the general economic depression that followed the war. Peters, who at various times in his life advertised himself as a lawyer, physician, and gentleman was repeatedly jailed for debt. He was probably in prison when Phillis died on December 5, 1784, when she was about thirty-one years old. The cause of her death is unknown, but it may have been related to the “Asthmatic complaint” she suffered from in previous winters. The first American edition of her Poems was not published until 1786, in Philadelphia.

Wheatley was not only the first person of African descent to publish a book, but consequently the first international celebrity of African descent

Wheatley was not only the first person of African descent to publish a book, but consequently the first international celebrity of African descent. She also founded the literary tradition of English-speaking authors of African descent. Although Wheatley never met her contemporaries Jupiter Hammon, an enslaved African-American poet, Philip Quaque, an African-born Christian missionary to Africa, or Ignatius Sancho, a renowned contemporaneous African-British author, they all knew of her and her writings. Sancho called her a “Genius in Bondage”.

Eighteenth-century opponents of the transatlantic slave trade, as well as nineteenth-century ante-bellum American abolitionists, cited Wheatley’s poetry as proof of the humanity, equality, and literary talents of people of African descent. But she and her work have not always been so highly valued. Arguments about the significance of Wheatley and her writings, from her own lifetime on, reflect the evolving re-assessment of African-American and African-British culture. Some commentators, Black as well as white, questioned the literary quality of her writings, or the political and social significance of her life, in support of their own ideological positions on whether and how people of African descent should produce literature. The most notorious critic was Thomas Jefferson, who denied that she was a poet. During the period from the late nineteenth century to the 1970s, a number of critics expressed neo-Jeffersonian denunciations of Wheatley’s literary abilities, as well as of her racial loyalty.

Phillis Wheatley’s place in the developing tradition of early transatlantic literature by people of African descent, and her role as the mother of African-American literature are now finally secure. The many ways in which she subtly and indirectly confronted the issues of racism, sexism, and slavery have been increasingly appreciated. The prophecy offered by the pseudonymous “Matilda” in “On Reading the Poems of Phillis Wheatley, the African Poetess” (New York Magazine, October 1796) has been realized:

A PHILLIS rises, and the world no more

Denies the sacred right to mental pow’r;

While, Heav’n-inspir’d, she proves her Country’s claim

To Freedom, and her own to deathless Fame.