Rowan Bell on the relationship between artist Pablo Picasso and poet Paul Éluard

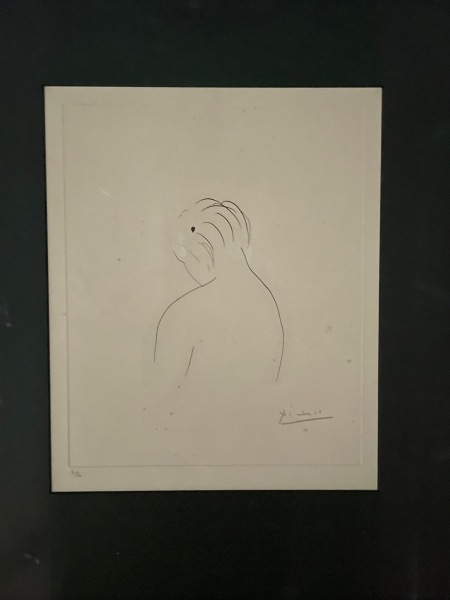

One of my favourite pictures by Picasso is also one of his simplest and least known. It depicts a woman’s back and head. Her hair is short and sparse, and there is a jewel above her ear. Although the drawing is only a few lines, it’s context and history are intriguing, and it is this I see when looking at its simplicity.

Picasso called it ‘Nu du Dos’ – nude back – and it is like an illustration from a medical textbook. The upper back is hunched in a slouched posture inviting the viewer to interpret this body shape being perhaps due to long periods of concentrated work with the upper body bent forward.

The picture was drawn in 1943 for his friend, the poet Paul Éluard, to raise funds for ‘Maison de la Midinette’ in support of the ‘Syndicat de la Haute Couture’, a union to provide relief to women exploited by the fashion industry – an exploitation depicted by the posture of the naked back. Eighty signed copies of the etching were made. Not all were sold and Éluard later donated the remainder in support of peace to the ‘Mouvement de la Paix’. The picture is evidence of the close friendship between Picasso and Éluard, and of the concerns both artist and poet had for the most vulnerable in society, even at a time when they were at the height of their fame.

‘Nu du Dos’ is evidence of the close friendship between Picasso and Éluard, and of the concerns both artist and poet had for the most vulnerable in society, even at a time when they were at the height of their fame

Éluard has an extraordinary life story, emotionally intertwined with some of the greatest artists of the period. As a child, whilst recovering from illness in a sanitorium in Switzerland, he met the young Russian Helene Dmitrievna Diakanova and fell in love. She was a major influence on his early understanding of great literature, introducing him to the writing of Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, but they were then separated by the tragedy of the First World War.

Éluard served as a soldier in the infantry, and was gassed. Romantically, he was eventually reunited with Helene in marriage in 1917 and – as a surrealist poet in Paris – he became an influential member of the Dadaist movement. But the marriage was complicated by a ménage à trois with Max Ernst, with whom Éluard was collaborating. He and Helene separated and Éluard subsequently wrote some of his most famous love poems:

The curve of your eyes circles my heart,

A circle of dance and sweetness,

Halo of time, nocturnal and sure cradle,

And if I no longer know everything I’ve been through

It’s because your eyes haven’t always seen me.

In the original:

La courbe de tes yeux fait le tour de mon cœur,

Un rond de danse et de douceur,

Auréole du temps, berceau nocturne et sûr,

Et si je ne sais plus tout ce que j’ai vécu

C’est que tes yeux ne m’ont pas toujours vu.

from Capitale de la douleur, published in 1926. Read the whole poem in French here.

Éluard and Helene divorced in 1930. Éluard married Maria Benz, known as Nusch; and Helene went on to have a relationship with Salvador Dalí. She is now perhaps better known under her name of Gala.

Éluard and Picasso became friends in 1935, just before the outbreak of the Spanish civil war. The depth of the friendship is expressed by Éluard in his book ‘Hommages’:

Picasso, here I see you, and I name you.

I have known your face for a long time, I see it quickly and see it slowly.

A face of my family, a big family made up of trusted friends, friends by day, friends by night, all quite beautiful, very different.

Picasso, ici, je te vois, et je te nomme.

Te connais ton visage depuis longtemps, je le vois vite et le vois lentement.

Un visage de ma famille, une grande famille composée d’amis très sûrs, amis de jour, amis de nuit, tous assez beaux, très différents.

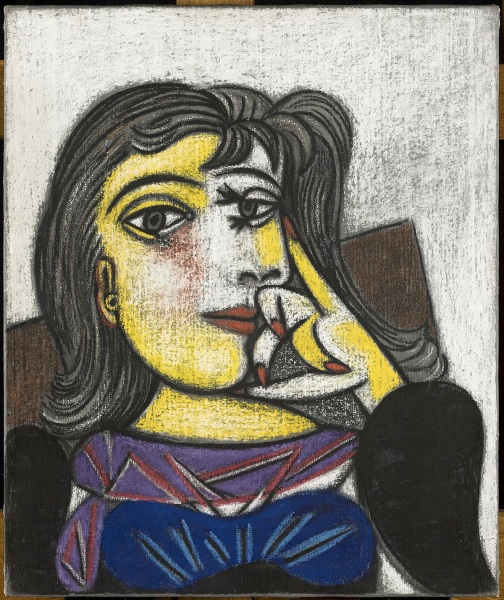

Before the civil war Picasso avoided politics, but as a famous artist he was pressurised to commit his name to the Republican cause and it was said that a political painting by Picasso could be worth a regiment in battle. Picasso’s political awakening was stimulated by Henriette Theodora Markovitch, known as Dora Maar, who was a well-established surrealist photographer and artist when she was introduced to Picasso by Éluard in 1936.

Both Picasso and Éluard were galvanised into radical action by the horror of war. It was after the bombing of an undefended town in 1937 by Nazi warplanes that Picasso painted his iconic masterpiece ‘Guernica’. Dora Maar’s photographs documenting the creation of Guernica reveal the intensity of the few weeks during which Picasso worked, and the painting became a political statement and fulcrum for public opinion.

Both Picasso and Éluard were galvanised into radical action by the horror of war

Éluard also used his skills against the horrors of war, and in 1945 he wrote the poem ‘Liberty’. Is it a great poem when devoid of its context and history? Probably not, but it is one of his better known because copies were dropped by the British RAF over Europe as part of the campaign against Nazi military aggression. The poem is driven by a powerful rhythm and repetition of the last line of each stanza, “I write your name”. The poem starts:

On my schoolboy’s notebook

On my desk and on the trees

On the sand on the snow

I write your name

‘Liberty’ ends:

And by the power of a word

My life returns to me

I am born again to know you

And to name you

Liberty

Another poem written in the same year is on a very different theme and is about those who are the most vulnerable in society. Entitled ‘Understand who will’ it is just a few lines about the treatment of women in war, but in contrast to ‘Liberty’ it is complex and nuanced. Éluard said of the poem “In that time, in order not to punish the guilty, they mistreated some whores. They even went so far as to shave their heads.”

Understand me who will

For me my remorse was

The hapless one who lay still

On the paving stone

Read about Paul Éluard on the Poetry Foundation

Seven things to know about Dora Maar at the Tate

BBC Radio on Picasso’s Guernica