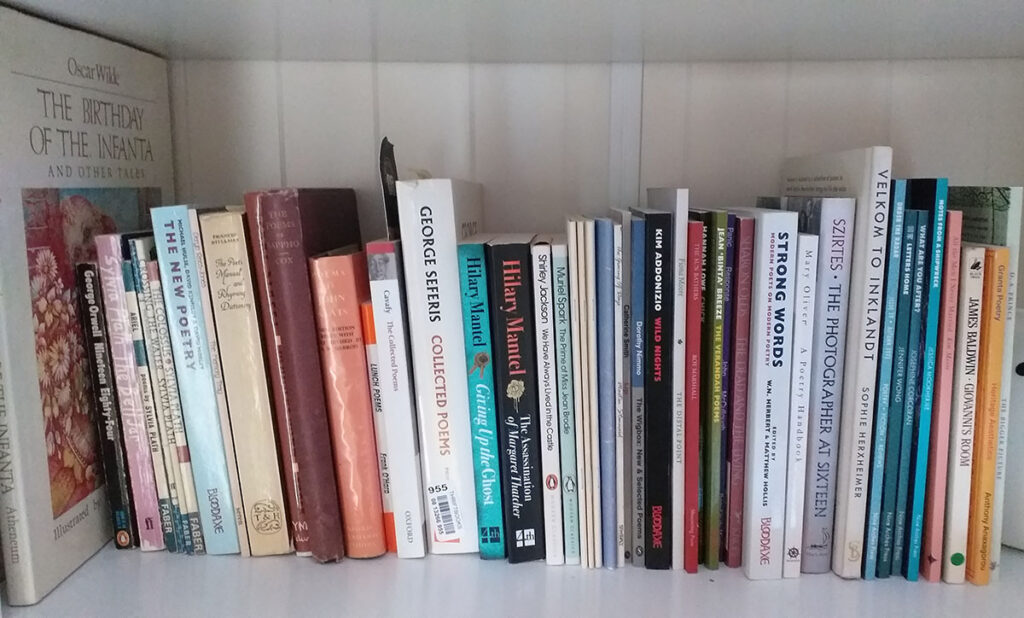

British Cypriot poet Maria Taylor takes a snapshot of her bookshelf and tells us why these books are important to her

Putting together this bookshelf has made me realise how much the books I’ve read have been like friends over the years. They have meant so much at different times of my life; a parallel life to the real one. I’ll begin with a childhood book. You’ll see an oversized book here, The Birthday of the Infanta, a book of abridged short stories for children by Oscar Wilde. There were not many books in our house when I was a child, so this stood out among the red-top tabloids, William Hill slips and TV Guides. I think I blubbed my way through ‘The Happy Prince’, ‘The Selfish Giant’ and the title story about the little boy who dies of a broken heart. When the pampered infanta announces, “For the future let those who come to play with me have no hearts”, it came as such a blow! As a child I didn’t care much about the differences between poetry and prose; both genres seemed to comfortably sit together. I’m sure these stories cultivated a love of lyric, image, and language.

Poetry began to creep in a more self-aware fashion when I was a teen, albeit poetry by the dead. I read the entire works of Sylvia Plath on the 266 bus from Acton to Hammersmith. Plath was very good but very dead. I also read Letters Home; a collection of letters from Plath to her mother Aurelia. I devoured The Bell Jar, and one of the English teachers caught me with it on a day I was wearing my trademark gothy black clothes and said I looked like “a picture of happiness”. Cheers. My inner compass gravitated towards Plath quite early on, and although I didn’t ‘get’ a lot of it I knew it was special. Other dead poets made a mark throughout student and degree days: T.S. Eliot holding “fear in a handful of dust” and Larkin’s trees “coming into leaf / like something almost being said”. I had mixed feelings at times. To be honest, I wanted to punch Andrew Marvell for ‘To His Coy Mistress.’ I felt a little queasy over his obsession with female body parts, although I liked his ‘The Mower Poems.’

Poetry usually came from a secret, magical part of Acton Library called ‘the reserve overflow’ collection. The librarian would vanish for a few minutes into some luscious underworld of writing and then reappear with something that could be mine and mine alone for a couple of weeks

Libraries were hugely important, both as quiet places to study and as sources of reading. My home life was pretty unsettled, so I hid in the library. Poetry usually came from a secret, magical part of Acton Library called ‘the reserve overflow’ collection. The librarian would vanish for a few minutes into some luscious underworld of writing and then reappear with something that could be mine and mine alone for a couple of weeks.

Things changed and I realised there was a living world of poetry. I would bet that many people come to poetry through reading anthologies. I enjoyed the ‘lucky dip’ quality that anthologies offered to me as a reader. Bloodaxe’s The New Poetry anthology changed my views on ‘dead poets’. It was the first contemporary anthology that came into my possession. You could dive in at any page and let the serendipity fairy of poetry do the rest. Among others, my favourites from The New Poetry were Eavan Boland, Geoff Hattersley, Selima Hill, Michael Donaghy, Carol Ann Duffy and Linton Kwesi Johnson. Johnson’s poem ‘Inglan is a Bitch’ was a refreshing, seminal moment.

Not all the books here on the shelf are creative works. A very special mention must go to Frances Stillman’s 1966 writing guide The Poet’s Manual and Rhyming Dictionary. I have a life-long habit of picking up second-hand books and when I brought The Poet’s Manual it was already dog-eared. The second half of this book is ostensibly a rhyming dictionary and was useful in the days before Google. The opening half, however, provided an apprenticeship in form. Frances (I must be on first name terms with my poetry godmother) taught me how to write in form and supplied all the rules; I tried all sorts of things, particularly villanelles, pantoums and sestinas. It’s not as if I write many poems in strict form these days, but Frances’ wise, no-nonsense teaching on form enabled me to get a poetic apprenticeship. It is necessary to know the rules before you break them. There are so many craft books out there, but this was my introduction to the weirdly addictive world of serious craft and inventive play. I still return to this book; I don’t intend to stop being a student of poetry.

And then the Greek poets. George Seferis’ poetry tapped into something which was there, but I hadn’t fully realised. My family are Cypriot, and my mother tongue is both Greek and the Cypriot dialect which draws from Greek. Seferis’ poems are stirring, very human and deal with loss:

[…] The times

happened to be unpropitious: war, destruction, exile;

sometimes the hunter hits the migratory birds,

sometimes he doesn’t hit them. Hunting

was good in my time, many felt the pellet;

the rest circle aimlessly or go mad in the shelters.

Those lines chimed with the displacement my mother’s family bitterly experienced. I was born four years after the Cypriot invasion, and it has left a scar. Seferis’ poetry offered a way into writing about war and exile.

… for years I would start every new notebook by writing out ‘Ithaca’ by C.P. Cavafy in Greek. It was a way of connecting with poetry, as well as a focusing method

I’ve gone out of the habit now, but for years I would start every new notebook by writing out ‘Ithaca’ by C.P. Cavafy in Greek. It was a way of connecting with poetry, as well as a focusing method. Surely every poet, or human being for that matter, carries their own version of ‘Ithaca’ within them:

And if you find her poor, Ithaka won’t have fooled you.

Wise as you will have become, so full of experience,

you’ll have understood by then what these Ithakas mean.

In a very different vein, I loved Catherine Smith’s 2009 collection Lip, and it’s a collection I read and re-read. Her poems are surreal and feisty; she writes about sex and relationships in a surprising and compelling way. Smith’s poetry is bold and surreal. Everyday things are turned on their heads. One poem begins in media res with a man “tightly bound” on a dominatrix’s table. This unfortunate soul has forgotten the “safe word” which is the name of a homely northern town he visited as a child. It happens to be the poem’s title, ‘Heckmondwike’. You feel like shouting it out to him. Smith has an inventiveness for dealing with complexity and dark humour. She’s one of my poetry heroes and her presence is missed. Many people say poetry has a ‘memory’ issue, so it’s an older collection I want to praise here.

Another strong poet for me is Jean Binta Breeze. The Verandah Poems was her last full collection and I have a signed copy, with a personal note inside, which I cherish. I met her at the WORD! poetry night in Leicester. Her performances were legendary and explosive. She covered a fierce range of emotions and taught me that poetry doesn’t need a set volume or style; it can be a spectrum of moods. Jean’s style could be affectionate and familial one moment then angry and political the next. The only thing that didn’t change was the surety of the voice. I remember at one reading she gave some advice to a young poet who she took the time to speak to after a show. It was quite simple. Be bold and don’t be afraid to write about the big things. This was contrary to advice to “write about the small things” that I was hearing in workshops. So perhaps, as with all poetry advice, take what you need to hear.

I’ve always looked forward to new poetry from John McCullough, from his debut The Frost Fairs to his most recent Panic Response. McCullough’s style is so individual and achieves that thing that very good musicians do, which is to offer a recognisable voice, even when playing with form and structure. I like the atmosphere and fluency of his poems:

To council estates where the glows of lone cigarettes

At night are souls drifting; to each corner beneath bridges

Where trolleys congregate, buskers cry; to the flat

Where a woman rises from under bathwater gasping.

(from Prayer for a Godless City)

Let’s also hear it for the pamphlets, which don’t stick out as much in this photo due to their deceptive smallness but have an immense influence. I have a few here, whose spines look more nondescript than the fatter books, but that’s the beauty of pamphlets. They feel more intimate. These are the ‘secret’ poems that somehow manage to find you. They slip into a pocket and join you on your travels. You can see the cream spines of HappenStance and the colourful ones of The Poetry Business here, but there are so many presses out there. I think one of my favourites, among too many is Fiona Moore’s The Only Reason for Time published by HappenStance.

Let’s also hear it for the pamphlets, which don’t stick out as much in this photo due to their deceptive smallness but have an immense influence

I’ve also been active as a Reviews Editor for Under the Radar, the Nine Arches Press flagship magazine, for several years. I include the latest edition here, along with some powerful Nine Arches Press titles. Editing is not an easy task in some ways, but it’s kept me up to date with new titles and emerging voices. For me, poetry reading has become about balancing a desire to look back and look ahead. In terms of looking ahead, I also include Anthony Anaxagorou’s most recent collection Heritage Aesthetics, which has really made me shift a gear in my outlook on voice in poetry and identity. We are both British Cypriot. It’s startled me and made me consider new ways of addressing related themes of identity. Again, that advice from Breeze about needing to think about writing poetry with a wide lens.

Throughout this bookshelf I’ve tried to weave in novels and collections which have meant something to me over the years. An inexhaustible task really! I can’t cover everything, but hopefully this provides a snapshot. I will finish with D.A. Prince’s latest collection, The Bigger Picture, which I treated myself to recently and is my next ‘to read’ book. I love Prince’s style and the mood of these poems. As a poet, Prince lessens the distance between certainty and mystery. It seems fitting, as I’ve written so much about the past, to draw this piece to a close with some lines from Prince’s poem ‘The Future’:

[…] How it shimmers, out there,

A beyond we can’t measure, out of time,

Erasing the words we pin on calendars. How

out of reach it is; how it could be anywhere,

Unfathomed, immaterial. How it’s not here.