Rowan Bell on impressionist painter Pierre Bonnard and the art of writing poetry

Pierre Bonnard was a quiet and unassuming man. In his self-portraits he depicts himself as myopic and vulnerable. His paintings eschewed classical tradition and form. Like Gauguin he used the asymmetric observer perspective of the Japanese prints he collected. This was not radical enough in some eyes and he was criticised by Picasso:

“Painting can’t be done that way. Painting isn’t a question of sensibility; it’s a matter of seizing the power, taking over from nature, not expecting her to supply you with information and good advice.”

Poets are familiar with this debate, ranging from “it’s not a poem unless it scans and rhymes” to “what we don’t like: forced rhyme, strict adherence to form at the expense of rhythm or sense” and the oft repeated “poetry died 100 years ago this month”.

Despite not doing it the right way, Bonnard was a profound influence on other artists, from the expressionist Gabriele Münter to the abstract colourist Mark Rothko. Today his work is exhibited in the world’s major galleries and sells for millions of dollars at auction.

Bonnard painted as if he was a poet writing a poem. Collecting images, colour and expression, and then melding them into the completed picture. Not that every poet writes this way. Some poets are like Jackson Pollock, spontaneously dribbling and dripping swirls of colourful words. Or like Yves Klein and his human paintbrush performance art in which the characters in a poem might energetically press their blue daubed naked bodies against a canvas in front of an audience.

Bonnard painted as if he was a poet writing a poem

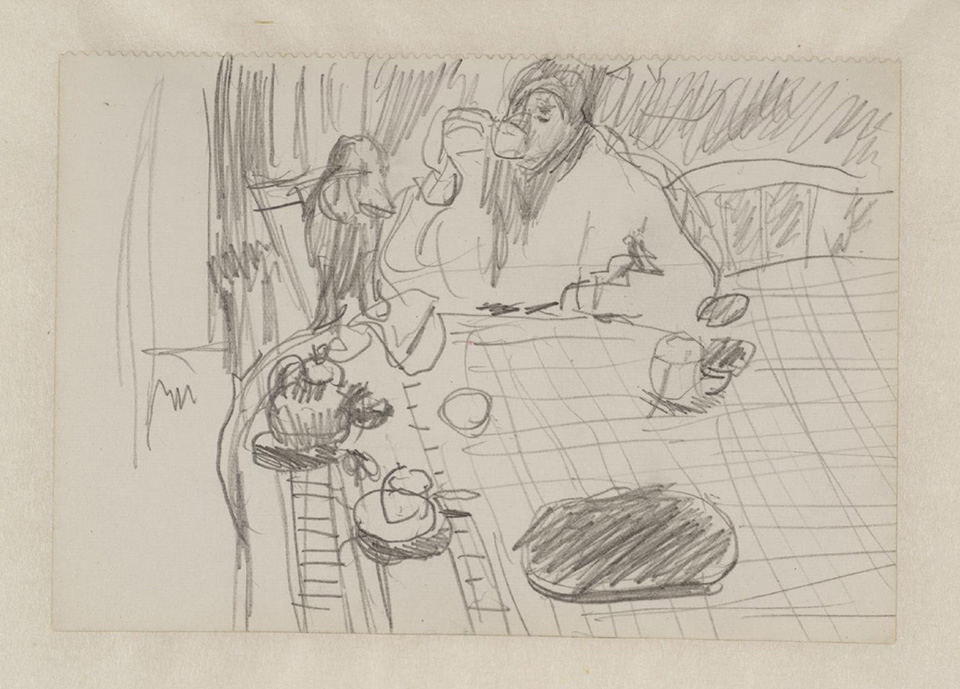

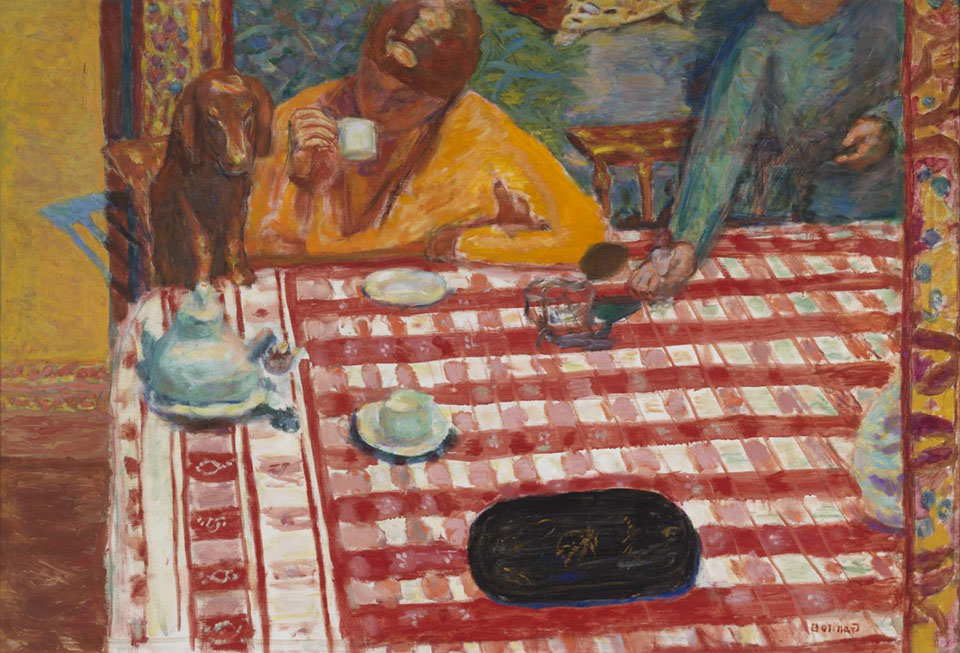

Bonnard worked from small intimate sketches. Like a poet he created fragments of everyday household detail. Simple truths and honesty. A woman sitting at a table drinking coffee, the cup to her lips. The table covered by a checked tablecloth. An empty chair to her left. On the chair to her right, a dachshund with its paws on the table.

These sketches would later be transformed into paintings and bright colour. The tablecloth white and vermillion red. The woman wearing a cadmium yellow dress. Ultramarine and cobalt blue in the shadows and in the mysterious arm of a woman reaching for a small glass on the table. An arm that wasn’t in the original sketch, but when added creates a movement and a story.

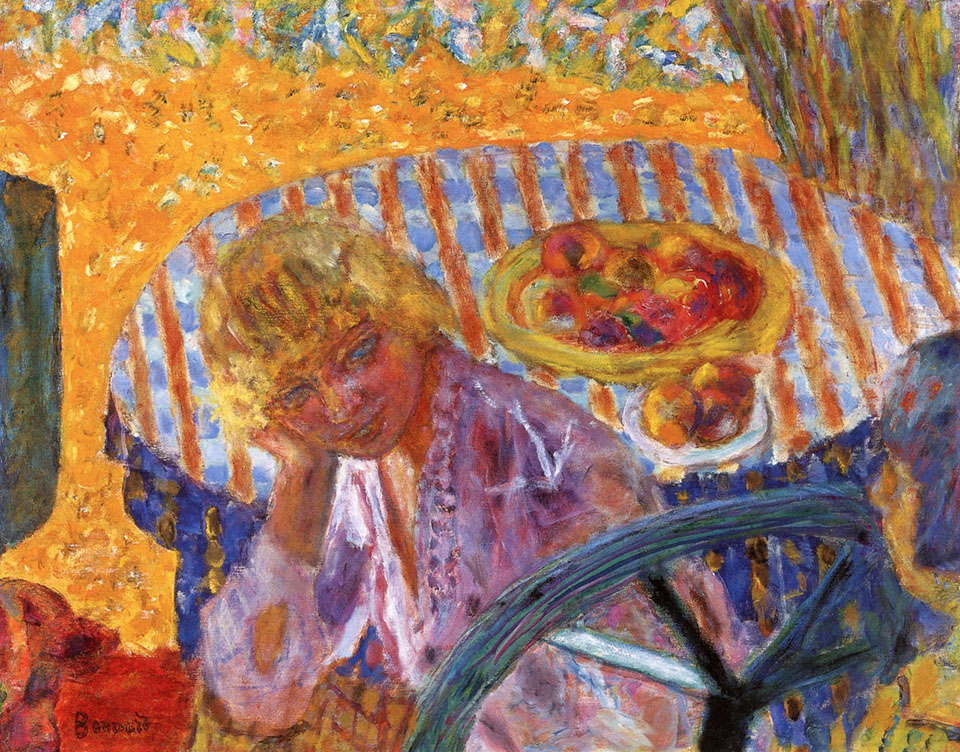

He worked on many canvases simultaneously, often taking a long time to complete a painting. Sometimes he would come back many years later and make changes. Most famously he did this to his painting ‘Young Women in the Garden’. In the picture the blonde Renée Monchaty is at the centre and the dark haired Marthe de Méligny on the right-hand edge.

Monchaty committed suicide two weeks after Bonnard married de Méligny. He recoloured the ground yellow two years before his own death and twenty-two years since he’d last worked on the painting when both women were alive. Poets do the same. Returning to poems about their tragically lost loves from decades before.

Read more about Pierre Bonnard at Escape Into Life, at the Tate, and at The Paris Review.