D.A. Prince reviews Old Friends by Hannah Lowe (Hercules Editions, 2022)

A good cover is an asset and Old Friends has a very good cover indeed. A map (Ordnance Survey sheet VII.70, London,1895) is wrapped round from the back, filling the front cover and continuing inside. We know it’s Limehouse because the name is printed in lemon capitals across the inky blue-grey of the streets. The title stands out in the same colour; next to it, Chinese characters, which I trust is Old Friends translated into Chinese. At first I thought the pamphlet format was square but it’s not, quite. At 125 mm by 140 mm it’s compact, hand-sized, as is Lowe’s other Hercules Editions pamphlet (Rock, Bird, Butterfly, 2022) with each poem partnered with a photograph.

Lowe’s two pamphlets from Hercules Editions make a good contrast. While Rock, Bird, Butterfly is about that luxury product Chinese wallpaper, Old Friends enters a totally different world – sailors, dock workers, restaurant owners, cooks, laundry workers. These were people who settled near where they arrived, living in their own close community. A four-page Introduction by Anna Chen, ‘How many Chinese are there?’, gives a necessary context to what she calls their ‘shadowy identities’. The first Chinese seamen were brought in by the British East India Company in the early nineteenth-century, taking the place of place of sailors enlisted to fight against Napoleon. They were cheap labour, a commodity.

Lowe’s two pamphlets from Hercules Editions make a good contrast. While Rock, Bird, Butterfly is about that luxury product Chinese wallpaper, Old Friends enters a totally different world – sailors, dock workers, restaurant owners, cooks, laundry workers

Worse than that, they became demonised – foreign, different, and a target for sections of the press, whipping up anti-Chinese rage among the white urban population by the early twentieth century. In the hundred years some things haven’t moved on. Now, as Chen (and Lowe) remind us, we have China demonised because of Covid-19 and economic threat.

That’s a lot of background but it opens the door to the poems – and poems are what we’re here for. A vivid, visual opening shows Lowe’s personal connections:

A white tablecloth, a spinning table, a heap

of hot spare ribs. Wine glasses hung from stems

above the bar, bells I wanted to tap

my chopsticks on. Old Friends, Good Friends, New Friends?

My brother remembers dad slapping the owner’s back.

[…]

Someone’s birthday? I can’t remember whose.

Only my bowl of won ton soup is clear,

pulled into focus through my mind’s binoculars.

There’s no title for the poem but the name in the photograph opposite will serve: Old Friends Restaurant. Two men in chefs’ whites, lean in the doorway, eyeing us. On the wall a metal street sign ‘Mandarin St, E.14’. It’s real place – circa 1950, according to the Acknowledgements. Typing ‘circa’ I realise how significant a haziness around precise detail becomes throughout this pamphlet. There are no major collections of written archive to draw on; nothing like all those letters, certificates, journals that underpin the histories of the tidy-minded English, the white population.

That final metaphor, “the mind’s binoculars” is what we all need for examining the past. I’m conscious that binoculars close in tightly on a small detail and not a broad sweep. Isn’t that how childhood comes back, via the immediacy of a favourite food, or something as strange as upside down wine glasses? Sight, taste, sound, touch – and I’m sure the spare ribs had a smell to stir memory. The scene is sketched and it’s personal. In a single poem Lowe has moved our focus from a socio-historical introduction to her family, via her Chinese-Jamaican father.

Where do you find connections to a past that was largely unrecorded? Lowe distills the archive photographs:

Limehouse. Run-down lodging houses. Seafarers

from Malaysia, Cape Verde, China. The Thames

laps the docks, hauls in the tea clippers –

the smell of oranges and ginger crams

the air. The photographs are monochrome –

the restaurants, shops and laundries lining Ming Street,

two Chinese men inspecting chickens in a crate

but I see colour.

I’ve quoted the first stanza of this two-stanza poem in full, not just for the dizzying list of trade and activity, but to show how Lowe uses her seven-line stanza in a sonnet-ish way. She seems relaxed in a seven-line form; it’s large enough to be conversational and rangey. It doesn’t feel restrictive in the way a more familiar sonnet form can be.

I’ve quoted the first stanza of this two-stanza poem in full, not just for the dizzying list of trade and activity, but to show how Lowe uses her seven-line stanza in a sonnet-ish way

Colour is what Lowe is bringing to the monotone past. Here the accompanying photograph is of Anna May Wong, an American actress of Chinese heritage, whom Lowe imagines in these London streets. Early films were often hand-coloured in an assembly-line process, as Lowe reminds us; it’s been legitimised by the anonymous workers of the past. She doesn’t labour this connection but it’s the first of many links to popular culture.

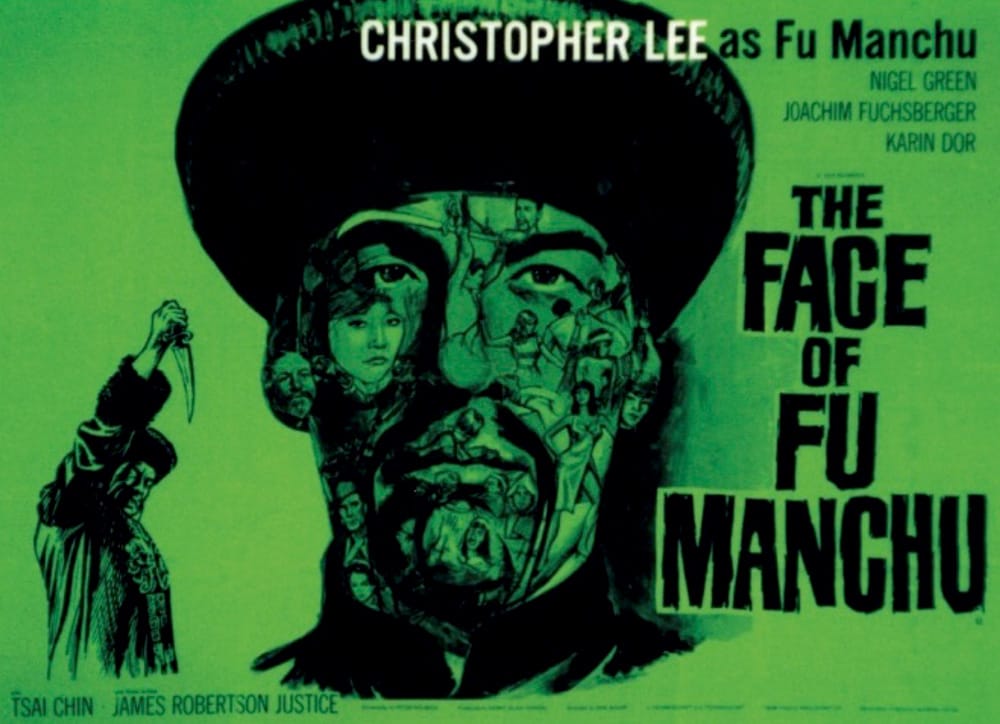

The yellow peril, incarnate in one man…

Deep below the waterways, Sax Rohmer

set the lair of Fu Manchu. No urge

to read the Mystery or its sequels. On the covers

a pair of long-nailed yellow hands emerge

like claws in darkness, above Chinesey letters.

His face is drawn like every fictive evil

Chinese face – sallow, evil-angled.

I watch The Face of Fu Manchu instead.

Christopher Lee in a sweeping black silk gown,

a double-slug moustache. In his riverbed

headquarters under Limehouse, he drowns

a double-crosser – she’s swallowed down

into the murky river water-tank

as Fu looks on, face yellow-powdered, blank.

Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu novels (from 1913 onwards, and subsequently filmed) poisoned the popular imagination with tales of an evil Chinaman, based in Limehouse. On the covers,

a pair of long-nailed yellow hands emerge

like claws in darkness, above Chinesey letters.

HIs face is drawn like every fictive evil

Chinese face – sallow, evil-angled.

How does Lowe counter this? With a a two-stanza poem about her son embracing the idea of his Chinese heritage, proudly telling everyone at school, the stanza break cleverly capturing the turn in his teacher’s initial disbelief.

I tell her Rory is

a little bit Chinese. No way? she says

then laughs, then blushes, her cheeks two rosy blots.

The language looks simple but beneath ‘blushes’ and ‘blots’ is something more complex, harder to admit: a mistake, and about identity. About race.

What does China mean to London now? In Lowe’s longest poem (four seven-line stanzas) she describes a lockdown walk through Limehouse with the poet Richard Scott, past ‘warehouses turned galleries’, seeing a tourist. The tourist is Chinese. A century ago the tourism was of a different kind –

[…] you’d pay T.Cook & Son three pennies

for a tour to colour in your fears

and fancies – Ladies, Gentlemen, just here,

beyond this door, a real life opium den!

And down this street, a murder!

Opium: part of the trade and China wars, touched with danger. Charles Dickens used an opium den in The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Sex is part of the frisson, too. ’Brilliant Chang’, one of the few poems with a title, moves from the real-life, highly-seductive drug-dealer by way of her father’s friend –

This makes me think of Tony

Chinn, my father’s Chinese gambling crony,

who in A View to a Kill, played the ‘Taiwanese

Tycoon’ In other movies, ‘Unnamed Japanese’

and ‘Unnamed Burmese Businessman’ and also

‘Oriental Agent’.

It could be such a slight anecdote but I find this sharpens what Lowe’s “mind’s binoculars” are seeing in the past. Here an individual, named and known, is reduced to a bit part with even his racial identity blurred, as though it didn’t matter.

In these confident poems Lowe lets the ideas play across the map, not just of London but a wider world. She gives the past – and her present – texture and colour

But poetry can preserve the past. In ‘Hauntology’ Lowe claims “My grandfather is captain of this book” and it’s his cooking (passed on to her father) that is another thread holding these poems together. From the won ton soup of the opening poem, through the “callaloo, / bok chai and bean sprouts” she cooks for her son, to the “boiled rice with sardines” in this final poem, food unites the generations.

The pamphlet closes with a six-page ‘In Conversation’ between Lowe and Richard Scott, partly about their walk and investigating the past but also about his own writing about Soho and “the fractured and incomplete archives of queer activities in this dense metropolitan area.” I’m not convinced that introducing a new focus, interesting though it is, entirely works at this point. It breaks the concentration on Limehouse and how the multi-faceted idea of ‘Chinese’, particularly as refracted through the media and popular culture. It’s a lively conversation but I wonder if is this the most appropriate place for it.

This is a complex pamphlet in its fusion of social and personal history. In these confident poems Lowe lets the ideas play across the map, not just of London but a wider world. She gives the past – and her present – texture and colour.

D.A. Prince lives in Leicestershire and London. Her second collection, Common Ground (HappenStance, 2014), won the East Midlands Book Award 2015. A further collection, The Bigger Picture, also from HappenStance, was published in autumn 2022.