More than the sum of its parts – Clare Best writes about her experiences of collaborative artistic work

Collaborative creativity

There seems to be an interest at the moment in the theories and workings of collaborative creativity. I wonder if this is in counterpoint to the First World’s love affair with a romantic notion of individual artistic genius that’s rooted deep in our cultural history. The cult of the individual, coupled with the cult of the author / artist, and a well-established competition and prize culture underpinned by capitalism, sustains a structure with a small number of successful ‘winners’ at the top of a wide pyramid of (often struggling) artists and makers. This is a huge and complex subject, but worth mentioning at the beginning of these two articles about my experiences of collaborative artistic work.

Collaboration is not the answer to creative work, in any arena, but a fact as well as an option in many of the arts, and it could be tried in many more. It so happens that writing (at least most writing for the page) remains largely a solo activity. And I’m not saying that areas of artistic endeavour such as opera, which are historically and traditionally more collaborative by nature, don’t have their problems. In fact they have particular and persistent hierarchies, and can be slow and stubborn when it comes to opening up and eliminating the ‘isms’, though change is now well under way.

All the collaborations I mention in these two pieces have been exceptional and productive, but each has of course needed plenty of work on the relationships, to keep the collaboration on the road. That’s just how it is. The hard work tends to be about constructing resilient frameworks and methodologies, learning to speak frankly, nip problems in the bud, and hash out difficulties in a way that is both emotionally intelligent and professional. I’m grateful to all the collaborators I cite here, and to others too, for their insights, for what they have taught me, and for the work we have made that could only have been made together.

Vertical collaboration and sideways collaboration

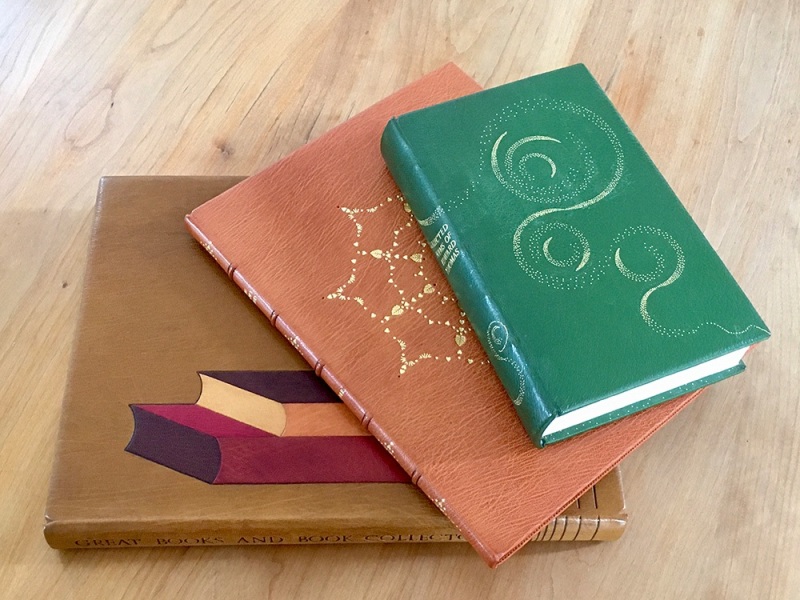

In my twenties, I trained and practised as a fine bookbinder. I really think bookbinding is the king of crafts – meticulous, mysterious, logical, unforgiving and fascinating work. Although I spent much of my time working alone, strangely enough those years of bookbinding grounded my creativity in the disciplines of collaborative working.

To bind a book well is to collaborate with different versions of yourself as maker, different stages of the process, at least if you undertake the entire operation solo, as I generally did. It’s a vertically integrated collaborative operation. I’ll explain. Unless the folded sheets are sewn skilfully, the book block will never be solid and suitable for binding; unless the spine of the sewn object is rounded correctly the book will not open or it may prove impossible later on to letter the covered spine; unless the boards are cut and attached accurately the object will not stand on the shelf; unless the book block is covered evenly and the corners mitred precisely, it won’t lend itself to the decorative elements of onlay or tooling with gold leaf. And within each major stage of making, there are countless other necessary stages, each reliant on the accuracy and success of previous steps. Nothing works well unless the close relationships between stages of making are acknowledged. To look at it another way, the making of a really beautiful book depends – at each turn – on imagination, foresight and dialogue: if I do this, this will likely happen; if I don’t do that, these are the problems I’ll run into later.

Later, when I worked in publishing, a sense of vertical collaboration also prevailed, although the various stages of production were usually spread between different individuals or departments.

Now, as a writer, I spend days and months sitting alone at my desk, and coaxing or herding words as I swim or walk. I love all this. And I like to think of this work also as vertically integrated craft – from emotion, ideas, notes, rough draft through to umpteenth draft, editing galore, etc. And I’m always working on at least one project that is essentially solo, or at least it’s solo to start with.

But I’ve also developed a passion for what I call sideways collaboration – working across genres, across artistic practices, reaching out and finding places at the edges of my work to meet other kinds of makers, inventing ways of talking over fences and making new and different things as a result.

Because I’m keen on lists, here’s a list of what I enjoy most about making work with other artists, in no particular order:

— The need to take risks, to experiment and play

— The kick of excitement right at the start of a collaboration that seems to show promise

— The invitation to trust

— The space that collaborators have to create and hold open for one another

— Serendipitous and synchronous moments, surprises

— Discovering how another artist works, being welcomed as a traveller in their terrain

— The focus on process as opposed to product

— Letting go of the notion of ‘me’ ‘I’ and ‘mine’ and embracing the realities of ‘us’ ‘we’ and ‘our’

— Not having to do everything myself

— Multiple transfers of energy and ideas

— When collaboration works, that realisation that the whole really is something very different from the sum of the parts – in fact the parts have disappeared into the whole

The visual was probably my dominant sense as a child, and my appreciation of the world came initially through a sense of visual wonder. I stand and stare, a lot. I marvel. So with that, and my background in designed and fine bookbinding, I was first drawn – as a writer – to collaborate with visual artists.

Breastless

I more or less fell into my first sideways collaboration. Due to a strong family history of breast cancer, I opted in 2006 for risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy. A few weeks before surgery I had my body photographed by Laura Stevens as a way of privately memorialising that version of myself.

Later I wrote a sequence of poems associated with the surgery, and then Laura suggested a further (post-operative) photo shoot. But it wasn’t until 2011 that photographs and poems first appeared together in print, and following that Laura and I spoke at events and I often exhibited or projected her images when I performed the poems, so her work was always at my side. My poems and Laura’s images worked powerfully in harness, complementing each other and doing good work in Medical Humanities settings as well as in more conventional poetry contexts. Our collaboration brought me courage and strength. The full project – Breastless – which grew from my collaboration with Laura Stevens can now be accessed on the Life Writing Projects website at the University of Sussex.

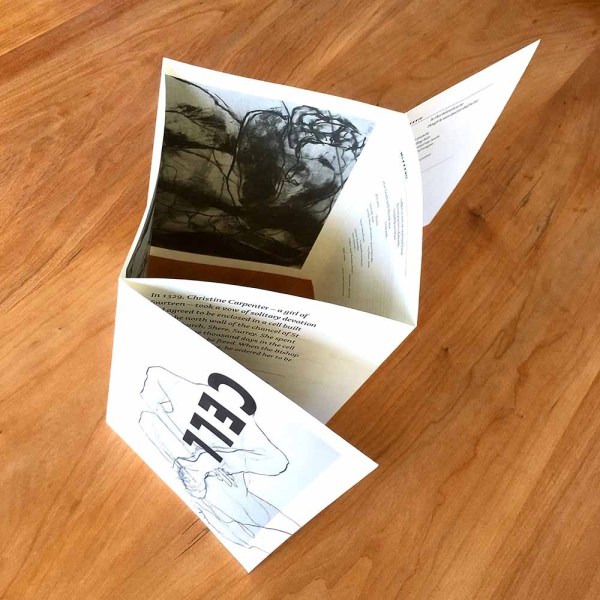

CELL

For CELL, I worked with artist Michaela Ridgway. The text, which I had written over several years, was already almost finalised when we started discussing her visual images and how to incorporate them into the object. Our working relationship grew organically through talk and experimentation. Michaela understood what I was trying to do with this long poem about female imprisonment, and our collaboration quickly clicked into place, with a mutual understanding that there should be complementarity and tensions between text and images.

The making of CELL also involved graphic designer Katy Mawhood who helped us realise an apt 3D form for the pamphlet-object of poem + images. In an interview with the poet Kay Syrad, I talk about collaborating with Michaela and with Katy.

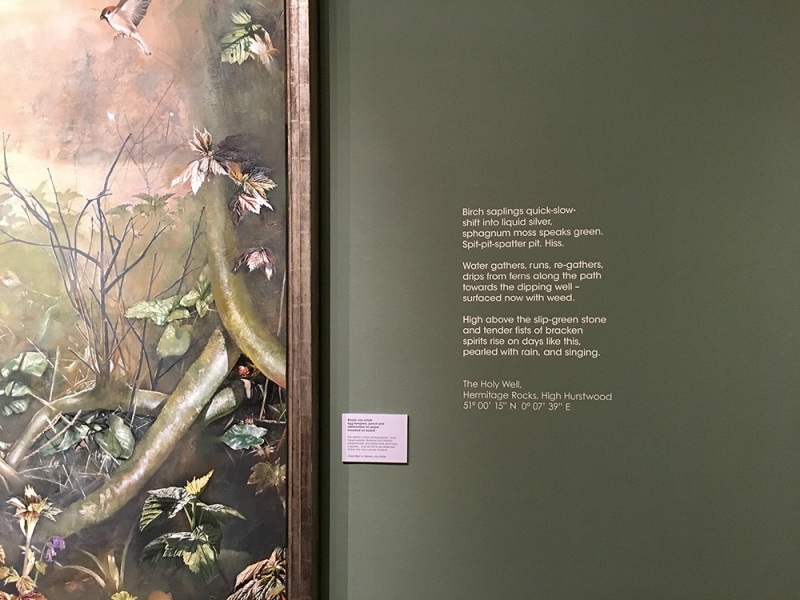

Springlines

The Springlines collaboration with the painter Mary Anne Aytoun-Ellis sprang from our simply agreeing ‘let’s work together one day’. And then we waited for the right moment, the right idea. The spark came from land and place – the fact that we had at different times both lived in the same house on the edge of the South Downs above Lewes. This contrasted with my collaboration with Laura Stevens, where life events had laid down the conditions and time-frame for the work.

Springlines was a long, slow collaboration, maturing over a period of more than six years. Mary Anne and I deliberately rejected the idea of working in any kind of illustrative and reciprocal relationship. Having decided, during the spring drought of 2012, to explore hidden and mysterious bodies of water in the south of England, we then worked in a triangle, the land or place being the primary source of inspiration for each of us, and one another’s work being a secondary source.

Throughout the project we talked at length about process, discovering many parallels in our approaches (for example: we both work with layering; we both look for ways of dissociating certain pieces from the places that originally inspired them; we both at times intentionally lose or destroy work in order to make it again differently) and in fact discussions around process became the driving force of our working relationship. Sometimes we would work in or from the same place, but with the freedom to interpret that experience quite independently; sometimes we each drew inspiration from different places and our dialogues around process would form the links between what Mary Anne was painting and what I was writing; occasionally one of my poems would influence Mary Anne’s work very directly, and vice versa.

In the body of work that we created and exhibited, much of which was later included in the book Springlines (Little Toller 2017) we held a long and unresolved conversation. To borrow a musical image, each of us sang a different line of music, but the result was a kind of harmony. A short film made by Sam Dynamou shows something of our collaboration during the New Forest stage of the project, when we were making site specific work to be shown at St Barbe Gallery in Lymington.

During preparations for three different exhibitions of our Springlines work – at Glyndebourne in 2015, Tunbridge Wells Museum & Art Gallery in 2017 and St Barbe Museum & Art Gallery, Lymington in 2018 – I learned how the public showing of visual art (which my poems for Springlines had become, at least in part, for those exhibitions) presents further collaborative challenges in the design for such a show, and the hanging of it.

Mary Anne and I had three aims when displaying our work in galleries:

— We wanted the poems to be reproduced at a scale that allowed them to be read as image almost as much as text.

— We wanted to avoid any sense that people ‘reading’ the poems would assume an obvious connection when ‘reading’ the paintings.

— It was important to us to exhibit the poems without titles, again to reduce the sense of captioning and to avoid associations with named places that had become, for each of us in different ways, anonymised in the making of both poems and paintings. We hoped that people looking at the poems and paintings would find the experience quite immersive, and enjoy the conversation between us as artists. Below each poem, in the exhibitions and in the book, I gave the geographic coordinates of the place that first inspired the piece, before place mingled with – and was transformed by – imagination, in the making of the poem. In this way, I honoured many of the sites of inspiration whilst, I hope, freeing the poems from being tied to specific places.

Vacant Possession

Vacant Possession also grew out of place. I co-wrote this piece of site-specific theatre in 2015 with Sara Clifford, the founder of Inroads. Sara and I were both Writers in Residence at the University of Brighton in 2015 and our collaboration on Vacant Possession grew from that year of working closely together. At the time, my family and I were preparing to leave our beloved home in Lewes where we had lived for more than sixteen years. Sara and I undertook substantial research into different elements and strands of the house’s history, so that we could portray the lives of previous historical occupants right up to and including my Springlines collaborator Mary Anne Aytoun-Ellis, and then my own family.

Vacant Possession, which was directed by Nicola Blackwell of Slot Machine Theatre, guided small audiences around the house to witness the drama of many immeshed stories, some of which featured ghosts. When recollecting the piece, I think of this work as principally visual, although it embraced poetry, drama, music. Strat Mastoris’ review is a good summary.

This experience of writing for live performance, and the excitement of collaborative stage work, must have got under my skin, to erupt a few years later when I decided to extend into making opera, possibly the most intensely collaborative and most challenging of all art forms. I’ll be talking about that, and also about Take Me With You, a uniquely intense collaboration with Tim Andrews, in Part Two next week on The Friday Poem.